Sullivan's Travels

1941

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Sullivan’s Travels is the work in which Preston Sturges most passionately and vehemently infused his art, combined with a re-examined vision of human affairs. The result was a fun, profound, and highly enjoyable film. We are at the dawn of the 1940s, a period when America, while emerging from the Great Depression, was preparing to enter the maelstrom of the Second World War. In this climate of uncertainty and social change, Sturges, one of Hollywood's most brilliant and unique writer-directors, created a true cinematic manifesto, distilling his genius by blending the exhilarating pace of screwball comedy with a bitter and penetrating reflection on the human condition and the role of art.

The story is that of John Lloyd Sullivan, a successful playwright who, tired of churning out "entertaining films for ignorant masses"—as he labels them with typically intellectual condescension—intends to write and direct a film about the humblest and most indigent strata of society. His intent is noble, perhaps, but imbued with a paternalism that the film itself will cleverly expose. To do so, he takes on the role by disguising himself as a tramp and begins to wander through the city to gather information, convinced that only direct experience can lend authenticity to his work. This premise, in itself, is already a common trope of Hollywood satire: the privileged artist who seeks "real life" among the outcasts, often with tragicomic results. His odyssey soon transforms into a whirlwind of adventures that will lead him to prison, accused of being his own murderer, a Kafkaesque paradox that highlights his loss of identity and the collapse of all bourgeois certainties.

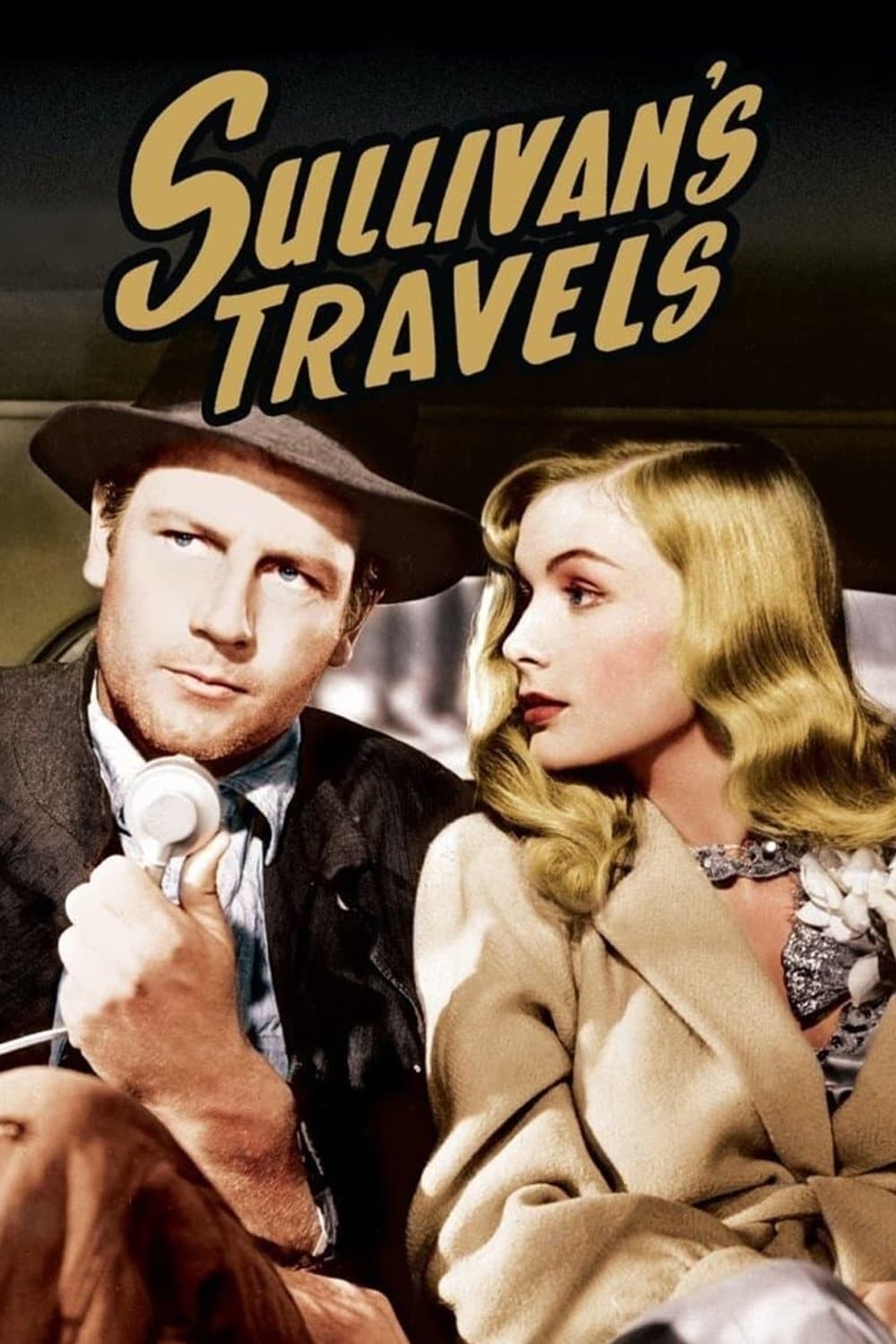

But redemption is just around the corner: both personal and artistic. He will, in fact, find love in the figure of a promising young actress (a magnetic Veronica Lake) who, with her disenchanted cynicism and frankness, proves to be the most authentic guide on this initiatic journey, and, above all, the dramatic inspiration. The film is permeated by a soft social critique, with a half-smile on its lips, but its true strength lies not so much in its portrayal of poverty—though effective and devoid of sentimental sugarcoating—as in its audacious meta-reflection on the very meaning of filmmaking and art in general. More than anything else for understanding this film, consider this exchange of dialogue between Sullivan and his butler: “I want to go out on the road to find out what it means to be poor people: to make a film about misery.” “If I may say so, sir, the subject is of no interest to anyone. The poor know everything about poverty: only intellectuals will like the topic.” “But I want to do it for the poor, don’t you understand?”

This dialogue is not just a simple exchange of lines, but the beating heart of a philosophical debate that runs through the entire history of cinema and art. The butler, with his pragmatic wisdom, dismantles the artist's presumption who, from his privileged pulpit, intends to "enlighten" those who live misery daily. Is it not perhaps the intellectual who, in the end, satisfies his own narcissistic need for "commitment" rather than an actual need of the public? Sturges here does not condemn empathy, but the vanity that often hides behind certain "socially useful" impulses in art. The film stands as a brilliant counterpoint to the at times simplistic populism of a Frank Capra or the seriousness of certain contemporary social dramas, while not denying their intrinsic validity.

True enlightenment for Sullivan arrives, paradoxically, in his darkest moment, when he finds himself in prison, forced into hard labor. Here, watching a cartoon screening for the inmates, he sees their collective reaction: thunderous, genuine, liberating laughter. In that chorus of forgotten joy, Sullivan understands the profound truth that cinema, and art in general, do not necessarily have to be vehicles of protest or instruction. Sometimes, their noblest and most necessary purpose is simply to offer an escape, a moment of oblivion, a glimmer of joy in an otherwise oppressive existence. Laughter becomes an act of resistance, medicine for the soul. It is a radical, almost heretical message, in an era that saw the birth of a more "committed" and realistic cinema, a prelude to Italian neorealism and other currents of social commentary. Sturges, instead, with an almost Brechtian mastery, tells us that entertainment is not an escape to be condemned, but a fundamental human need, capable of saving and uniting more than a thousand sermons.

Sullivan's Travels is not only a hilarious comedy and a madcap adventure; it is a visual essay on the artist's responsibility, on the illusory nature of privilege, and on the intrinsic dignity of every individual, regardless of their social status. It is a film that, while speaking of Hollywood and its foibles, transcends its time and context to deliver a universal lesson on the cathartic power of humor, an ode to joy, and the ability to find light even in the deepest darkness. A film that continues to be extraordinarily relevant, a reminder for all who think that art should always and only be a faithful mirror of a painful reality, forgetting its oldest and most sacred power: that of enchanting, uplifting, making people laugh, and, in doing so, saving.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...