The American Friend

1977

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Wim Wenders in a noir work adapted from a Patricia Highsmith novel, but not a simple transposition. Wenders, with his unmistakable sensibility, appropriates the literary material to make it a vehicle for reflection on identity, guilt, and the ambiguous attraction to the dark side that permeates much of genre filmography and literature. Highsmith, an undisputed master in delineating the most subtle psychological shifts and establishing a fluid and unsettling morality in her characters, finds in Wenders an interpreter capable of visually translating the atmosphere of unease and latent tension that characterize her pages, stripping the narrative of any superfluous embellishment to focus on interior corrosion. In this sense, The American Friend deviates from the more polished film versions of Ripley, such as Minghella's The Talented Mr. Ripley or even Clément's classic Purple Noon, to embrace a rougher grain, almost documentary-like in its psychological rawness.

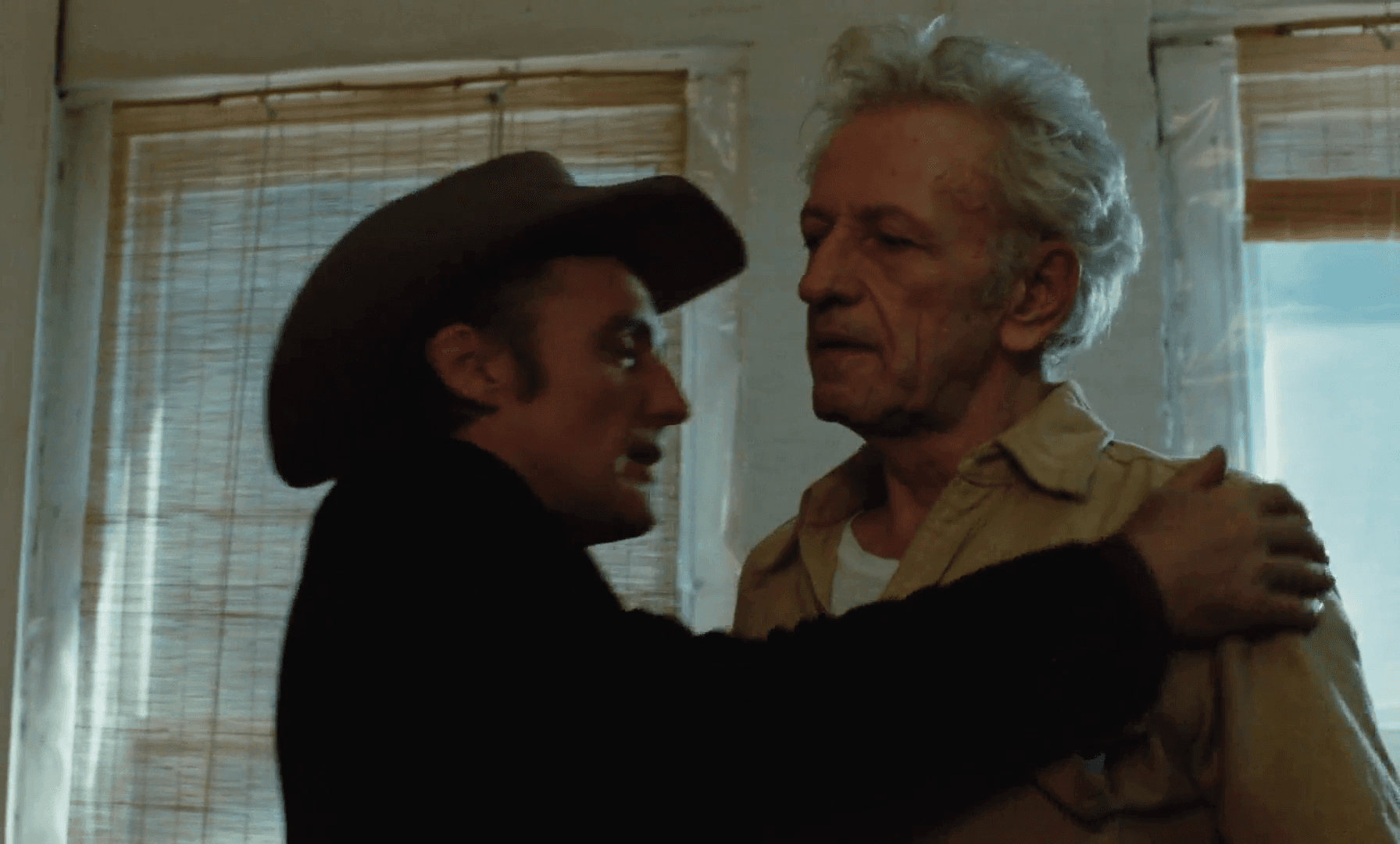

It is noteworthy how numerous directors appear in supporting roles in this film: Nicholas Ray, Daniel Schmid, Peter Lilienthal, Samuel Fuller. All filmmakers, particularly Fuller and Ray, whose gangster movies set a standard and to whom Wenders paid homage with a cameo in the film. This choice is not merely an erudite citation or an affectionate tribute; it is, rather, an act of profound cinephilia and a programmatic manifesto. Wenders does not simply feature his masters and colleagues; he places them within a narrative context that reflects on the dynamics of cinema itself. Nicholas Ray, the legendary director of Rebel Without a Cause and Johnny Guitar, here in the role of the forger artist Derwatt, is a shadow of himself, a dying and almost spectral man who seems to embody the twilight of a certain classic Hollywood. Conversely, Samuel Fuller, whose cinema was synonymous with raw energy and narrative impetus, here appears in his typical role as a brusque but charismatic gangster, almost a living anachronism that reasserts the indomitable vitality of genre cinema. This gallery of familiar faces from the "New German Cinema" and the American golden age transforms the film into a kind of intergenerational conversation about cinema, the craft of storytelling, and the weight of artistic legacy, making The American Friend a deeply meta-cinematic work, a journey not only into noir but into the very history of the seventh art.

The story is that of Tom Ripley, an art dealer and small-time con artist (Dennis Hopper), who is commissioned a murder by a gangster he owed money to. Ripley, having learned that Jonathan Zimmermann (Bruno Ganz), a small-town picture framer, is terminally ill with leukemia, transforms him into a hitman to commit the assassination in his stead, promising him money. It is here that Highsmith's genius and Wenders' vision merge in delineating a perverse and fascinating relationship. Ripley is not just a manipulator but a kind of amoral demiurge who creates a monster, or perhaps reveals the latent monster in an ordinary man. His friendship is a form of contagion, a poison that creeps into Zimmermann's ordinary life, plunging it into an abyss of violence and fear. Ripley will ultimately realize the abyss into which he has thrown the framer and will attempt to save him from the retaliation of the gang that commissioned the murder. This turn, from pure manipulation to a twisted sense of loyalty, elevates the film beyond a simple thriller, transforming it into an exploration of emotional dependency and morality on the brink. Ripley's "goodness" is ambiguous, perhaps dictated by a need not to be alone, not to lose the only person with whom he has established an authentic, albeit unhealthy, connection.

The Ganz-Hopper pairing is perfect: a seamless synergy and naturalness as if they were one man. Dennis Hopper, at the peak of his counter-cultural and rebellious iconography, brings to the screen an unpredictable, feverish Ripley, a bundle of taut nerves beneath a mask of affable cordiality. His Ripley is the embodiment of a certain disillusioned America, both fascinating and dangerous. Bruno Ganz, for his part, delivers a masterful performance, woven with a palpable vulnerability and a quiet dignity. His transformation from a simple, honest man, driven by the desperation to secure a future for his family, to a reluctant killer is painful and credible. Their on-screen chemistry is the film's backbone, a macabre ballet between victim and executioner that progressively transforms into a kind of aberrant symbiosis, a double bind where identities blur and roles reverse.

Wenders, after his almost pioneering German period – dotted with intimate and itinerant works like Alice in the Cities and Kings of the Road, where the dimension of travel and inner search often defined the narrative and visual structure – for the first time had substantial production means at his disposal to realize his project. This does not diminish his authorial signature in the slightest; on the contrary, it allows him to amplify his vision, casting his melancholic and contemplative gaze into a noir universe which, while intrinsically American, is filtered through an exquisitely European sensibility. The film's visual aesthetic, curated by the faithful Robby Müller, is a striking example: the neon lights cutting through the darkness of European metropolises – Hamburg, Paris, Munich – and the dense shadows enveloping the characters create a suspended, dreamlike yet tangible atmosphere, typical of New German Cinema yet imbued with an almost reverential homage to Hollywood classics. Each shot is a canvas painted with dark tones and violent contrasts, reflecting the characters' state of mind and the inescapability of their destiny.

A work with very tight pacing, dynamic, engaging, well-shot, pulsating with a nervous energy and an almost palpable suspense. The soundtrack, with its minimalist tones and rock incursions by bands like The Kinks, contributes to creating a unique atmosphere, halfway between melancholic and unsettling, perfectly aligned with the film's tone. With two great actors and a truly engaging narrative plot, The American Friend is not only a superb psychological thriller but also a profound meditation on friendship, the corruption of innocence, and the perverse allure of evil. Wenders offers us a masterpiece that transcends genre, a film that remains etched in memory for its unique atmosphere and its bold reinterpretation of a narrative archetype. What more could one ask of a film? Absolutely nothing.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...