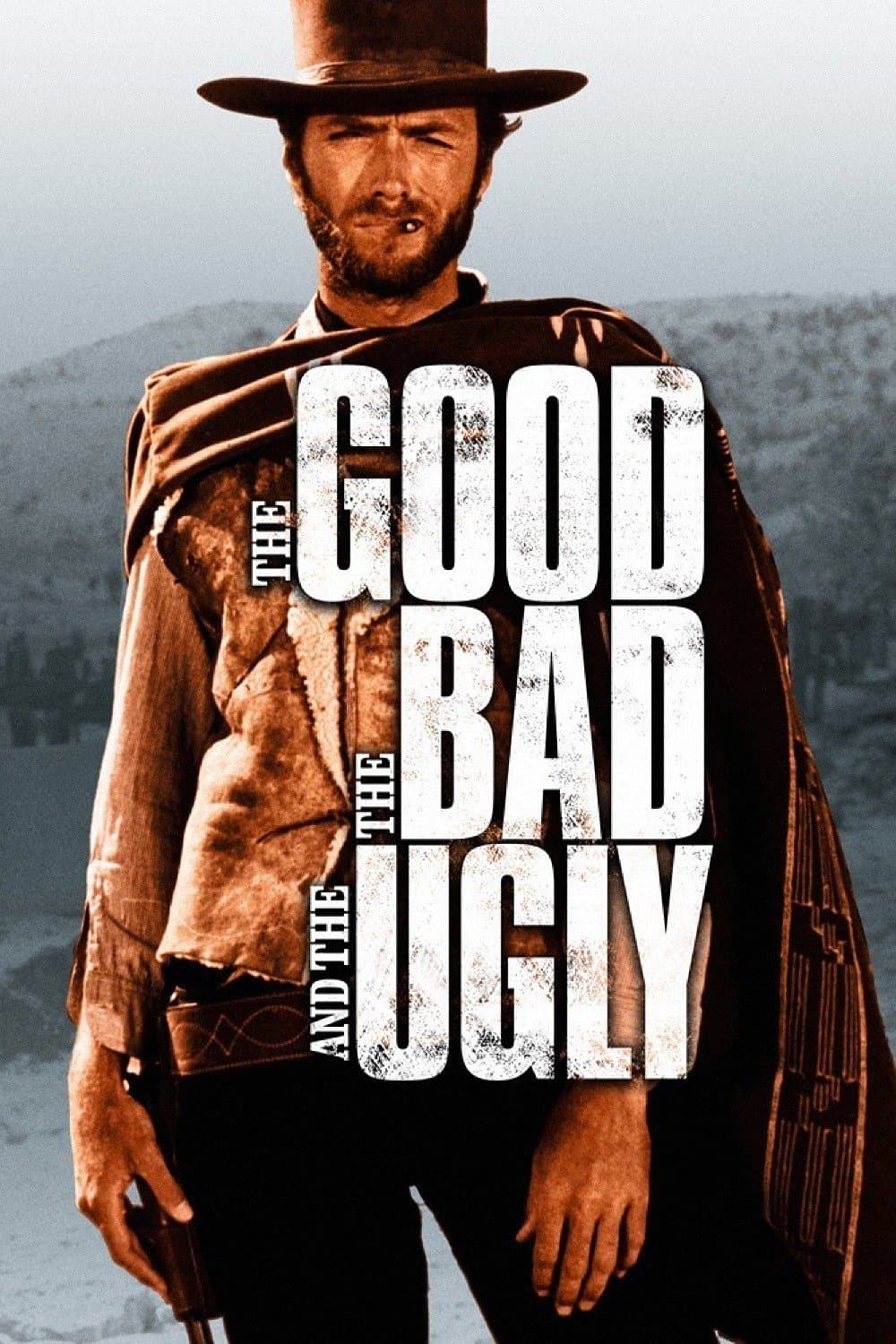

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

1966

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

A tour de force from Sergio Leone, a film that literally uproots the classic canons of the western to deliver a work of impressive vividness, of formidable power. If the American western, with totemic figures like John Ford and his morally irreproachable heroes, had sculpted the epic of the frontier in marble, Leone shatters these sculptures, scattering dust over a desolate and brutal moral landscape. His is a radical deconstruction, an iconoclastic operation which, far from destroying the genre, elevates it to new, unexpected heights of complexity and lyricism. It is the birth of a new archetype, that of the "spaghetti western," a genre that transcends a mere geographical label to establish itself as a true aesthetic and narrative current.

Having reached the third chapter of the so-called "Dollars Trilogy," after "A Fistful of Dollars" (1964) and "For a Few Dollars More" (1965), Leone realizes his idea of cinema: to stage the concept of Greek myth, that is, to place man at the center of the story with his intolerable vices and his pettiness. The Fordian hero, bearer of civilization and justice, gives way to the Leonean anti-hero, a creature of the desert and thirst, driven solely by the pursuit of profit and survival. These are not mere outlaws, but archetypal figures of a primordial, almost pre-moral human condition, in which civilization is a mirage and animal instinct the only guide. Their epic is not one of conquest or redemption, but of the perennial and squalid struggle for a fistful of dollars.

Three characters vie for a fortune and chase it through the American Civil War, a historical context far from accidental. The War of Secession is not a mere backdrop, but a primordial force that embodies the very violence, chaos, and senselessness that animate the protagonists. The fratricidal conflict between North and South reflects the aimless brutality that permeates every interaction among the three, transforming the battlefield into an extension of their corrupted psyche. Leone does not merely show us the war; he makes us feel it, makes us breathe it, with its dust, its blood, and its horrors, emphasizing the absurd futility of life and death in an era without ideals.

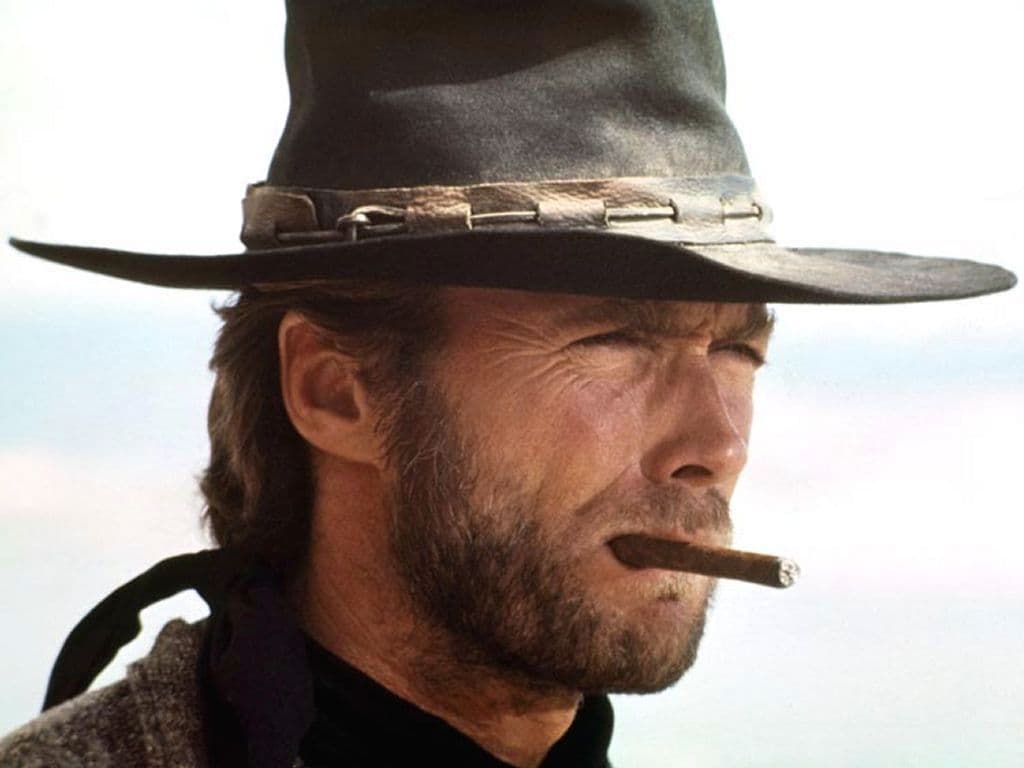

Each of the three has unsettled scores with the other two, a web of deceptions and opportunism that defines their precarious coexistence. Blondie (Clint Eastwood), enigmatic and laconic, embodies the "good" only by contrast, but his morality is as ambiguous as the desert shadows. He hands Tuco (Eli Wallach), the indomitable "ugly" with caustic verve, over to the authorities to collect the bounty, then he ambushes and shoots the rope that is supposed to hang Tuco with his rifle, then he goes off in search of a new sheriff and a new bounty to collect. This routine, repeated with cynical precision, symbolizes their parasitic bond: a deadly dance of betrayed trust and conditional salvation, where danger is always a pretext for gain. It is an anomalous symbiosis, almost an infernal marriage, founded on mutual utility and the awareness that neither can truly trust the other, yet needs the other to survive.

The encounter with the enigmatic gunman Sentenza (Lee Van Cleef), the glacial "bad" whose cruelty is matched only by his efficiency, will change their lives, introducing a third vertex of pure and unstoppable malevolence. Sentenza has no weaknesses or moral dilemmas; he is a machine of destruction, the embodiment of indiscriminate violence and the thirst for power. His presence raises the stakes, transforming the treasure hunt into a descent into hell, an allegory of man's fall in a world devoid of ethical reference points.

A revision and sublimation of the western genre through the litmus test of baroque characterization. Leone employs extreme close-ups that transform faces into landscapes furrowed by fatigue and despair, of gazes that are more eloquent than a thousand dialogues. Every wrinkle, every scar, every grain of dust on a hat contributes to sculpting characters that are both hyperreal and mythical. The baroque aesthetic manifests itself in the grandeur of the battle scenes, in the silent sequences charged with tension, and especially in Ennio Morricone's soundtrack, which does not merely accompany the images, but becomes a narrative voice in itself, an indispensable dramaturgical element. His atypical melodies, made of whistles, vocal harmonies, dissonant percussion, and Tuco's iconic theme, transcend the function of mere musical commentary to become an intrinsic expression of the characters' souls and the desolation of the spaces. Morricone's music is a brilliant counterpoint to the dialogic parsimony, filling silences with profound meanings and anticipating emotions with an almost operatic power.

The expressive force stems not from a linear story nor from the grand emotions deployed in the traditional sense of a melodrama, but from the brutal realism of the characters that animate the narrative. There is no room for romantic idealizations or heroic trajectories. These men are dirty, sweaty, hungry, driven by primal impulses. Leone's work is thus mythopoietic: to stage the smell of flesh, the warmth of blood, the sensation of dampness on the skin, the bitter taste of dust. It is a cinema that appeals to the senses more than to reason, enveloping the viewer in a tactile and visceral experience. The long shots, the extreme long shots that engulf almost insignificant human figures against the vastness of the landscape, alternate with extreme close-ups that probe the abyss of eyes, of mouths contorted by pain or by the grimace of a mocking smile. It is this contrast between the macro and the micro, between the epic and the intimately human (or inhuman), that lends "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" its timelessness and its inexhaustible charm, making it not only a masterpiece of the western, but a monument of world cinema.

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...