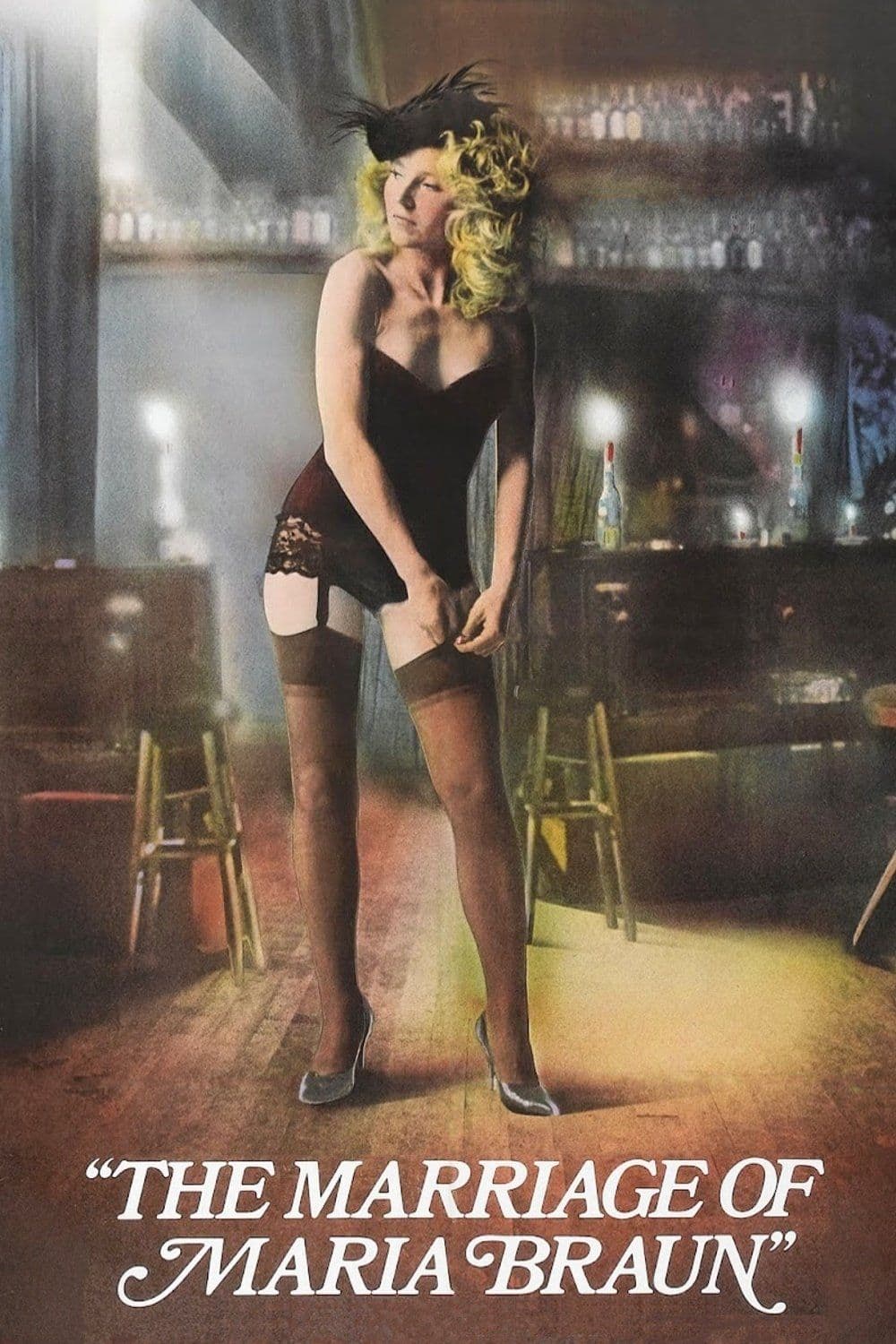

The Marriage of Maria Braun

1979

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Rainer Werner Fassbinder is a director who undoubtedly injected new life into the German cultural scene of the 1970s, not only from a cinematic perspective but also theatrically and narratively. But to define his contribution simply as 'new life' is almost an understatement. Fassbinder was a true enfant terrible of German cinema, a creative volcano whose prolificacy and acute social and aesthetic sensibility made him the most emblematic and irreverent figure of the New German Cinema. He did not merely infuse vitality; his work represented a ruthless and necessary examination of the historical and social pathologies of post-war Germany, a digging process that had few equals in depth and expressive brutality. His cinema, deeply indebted to the Hollywood melodrama of a Douglas Sirk – a master whom Fassbinder fervently admired and reinterpreted in an exquisitely critical and disenchanted key – used genre conventions not to reassure, but to unmask bourgeois hypocrisies and the unresolved wounds of a nation searching for identity.

In this film, The Marriage of Maria Braun, a true pinnacle of his filmography and the first chapter of his 'Federal Republic trilogy' (completed by Lola and Veronika Voss), Fassbinder elevates melodrama to an instrument of historical-social analysis. It analyzes the life of a woman married to a World War II veteran: defeat, disillusionment, and a lack of cultural references will punctuate her life, making her a paradigmatic figure of that Germany newly emerged from the ashes. Maria is the personification of an entire country: a nation devoid of ideals, morally devastated, that must rebuild itself from nothing, often at the cost of ethical compromises and a profound inner alienation.

Maria is a passionate woman; she falls in love with a young sergeant, Hermann Braun, who is leaving for the front, and marries him only to lose him in the maelstrom of war the very next day. But her passion is not merely romantic; it is a primordial force, an indomitable will to survive and prosper in a world seemingly intent on destroying her. Maria will wait for him in vain, going to the train station every day, hoping to see him appear on one of the arriving trains, in an almost Beckettian waiting that takes on a powerfully symbolic meaning: it is the waiting of a nation trying to recover a lost past, a normality that perhaps never existed. But reality asserts itself with its brutality, and a friend of her husband's announces his death.

With her husband presumed missing, Maria turns to prostitution, working in a brothel for American soldiers, and thus meets a Black American officer, becoming his lover. This transition is not merely a choice of survival, but Maria's first, stark step towards cynical adaptation to the post-war era. Her body becomes a commodity, a means to obtain food and shelter, reflecting the precariousness and desperate pragmatism of a society in disarray. The presence of the Black American officer, Bill, is significant: he is an "other" in a Germany that was redefining itself, and his killing is an act that seals the fate of Maria and Hermann, binding them indissolubly in a spiral of sacrifices and compromises. When Hermann reappears, having miraculously escaped the German defeat on the front, he kills the American lover to protect her. The man, in turn, to protect Maria, ends up in prison, taking the blame for the murder. This exchange of roles, this sacrificial interdependence, is the perverse cement upon which their relationship is founded, a relationship nourished by absence and a love distorted by necessity.

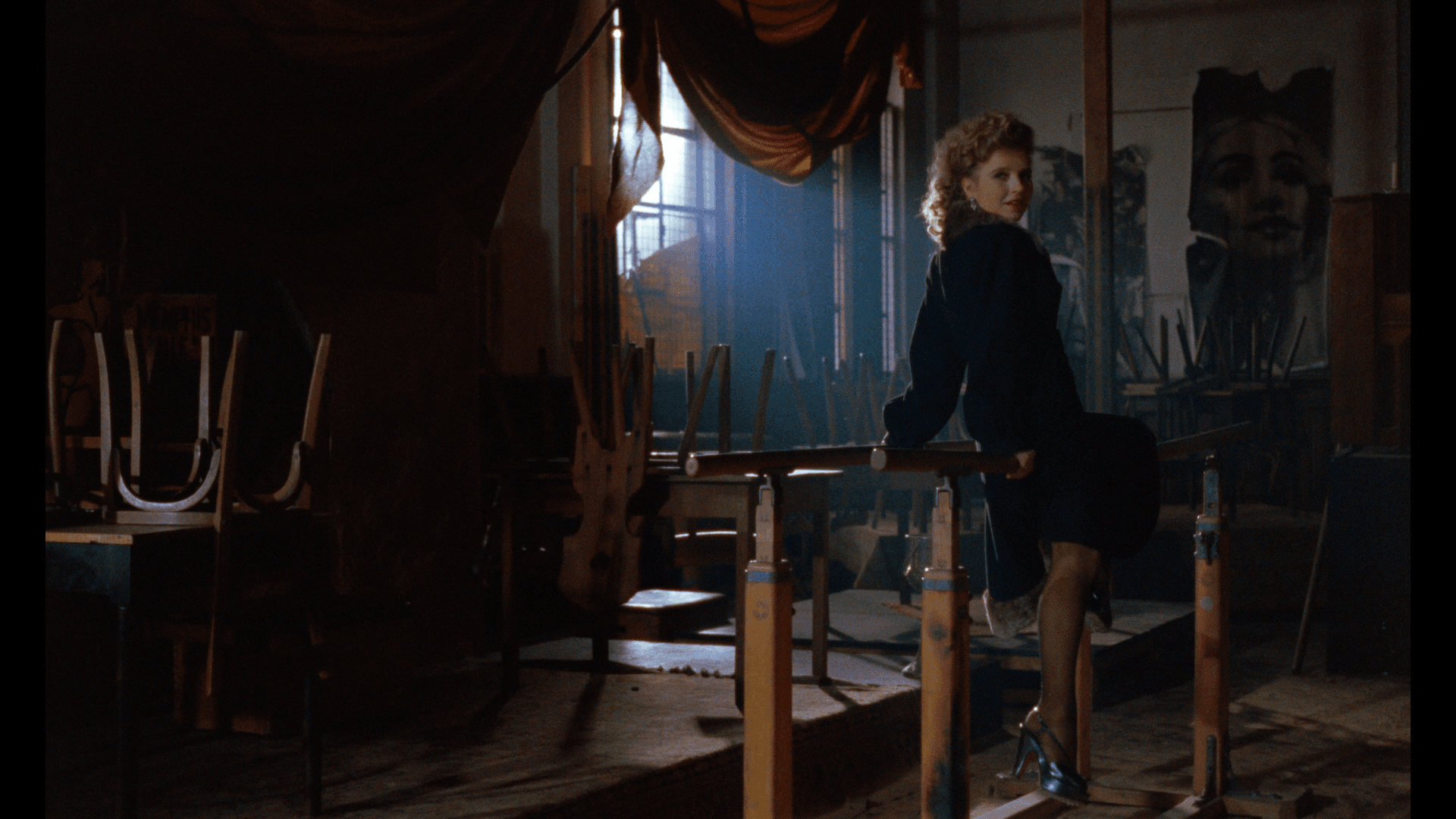

Meanwhile, Maria becomes the companion of a wealthy French industrialist, Oswald, discovering she has an excellent business sense and quickly becoming a skilled manager. This ascent is swift, almost dizzying, and reflects the Wirtschaftswunder, the German economic miracle that saw the nation rise from its ashes with astounding speed. Maria embodies the ambition, unscrupulousness, and adaptability that were the cornerstone of that period. Her clothes become more elegant, her dwellings more luxurious, but her face, magnificently portrayed by Hanna Schygulla – Fassbinder's muse and alter ego, whose cool yet wounded expressiveness is central to the character's success – progressively becomes harder, more impenetrable. Schygulla manages to convey the glacial solitude lurking behind the apparent success, an echo of which resonates in other Fassbinderian female portraits, such as those of Lola or Veronika Voss, women who, despite their power, remain prisoners of masculine and capitalist systems.

In this whirlwind of events, Maria never abandons the hope of one day embracing Hermann again and leading a normal life with him. But this hope is a mirage, a desire for lost innocence. The 'normality' Maria craves is a chimera, an illusion that brutally contrasts with the reality of her existence, woven with sacrifices and acquired cynicism. Her entire existence is an artificial construct, a house of cards destined to collapse as soon as the facade crumbles. The metaphor of Germany in full post-war reconstruction hidden behind the character of Maria is all too clear.

The tenacity, strength, and cynicism that permeate Maria's actions are the qualities that allowed Germany to recover, but at what cost? Fassbinder offers us a lucid and ruthless insight into post-war Germany, coldly analyzing the elements that led it to become one of the greatest nations in the world despite its almost complete destruction. But the director does not merely celebrate resilience. He reveals the deep cleavage between material success and the spiritual emptiness that results from it. The Germany of the Wirtschaftswunder is a nation that chose to forget its past, to bury its wounds rather than confront them, focusing solely on economic progress. Maria is the personification of this collective amnesia and the emotional cost it entails. Her ascent is the triumph of will, but it is also the failure of the soul, an existence emptied of authentic connections and human warmth, replaced by the cold logic of profit and accumulation. The ending, with the house exploding and the portraits of the Federal Republic's chancellors scrolling in the credits, is a stroke of genius, a sharp and utterly bitter commentary: Germany, reborn from its ashes, is perhaps a ticking time bomb, an unstable entity built on foundations of denial and repression. The physical destruction of Maria and her house is the ultimate metaphor for an intrinsically fragile wealth and stability, for a destiny that cannot escape its own contradictions. Fassbinder, with his unmistakable visual audacity and sharp intelligence, does not merely tell a story; he dissects an entire era, inviting us to reflect not only on how a nation rises, but on why and, above all, on what it sacrifices on the altar of progress. The Marriage of Maria Braun is, ultimately, a monument to Fassbinder's genius and an essential work for understanding the cracks and magnificences of an entire era.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...