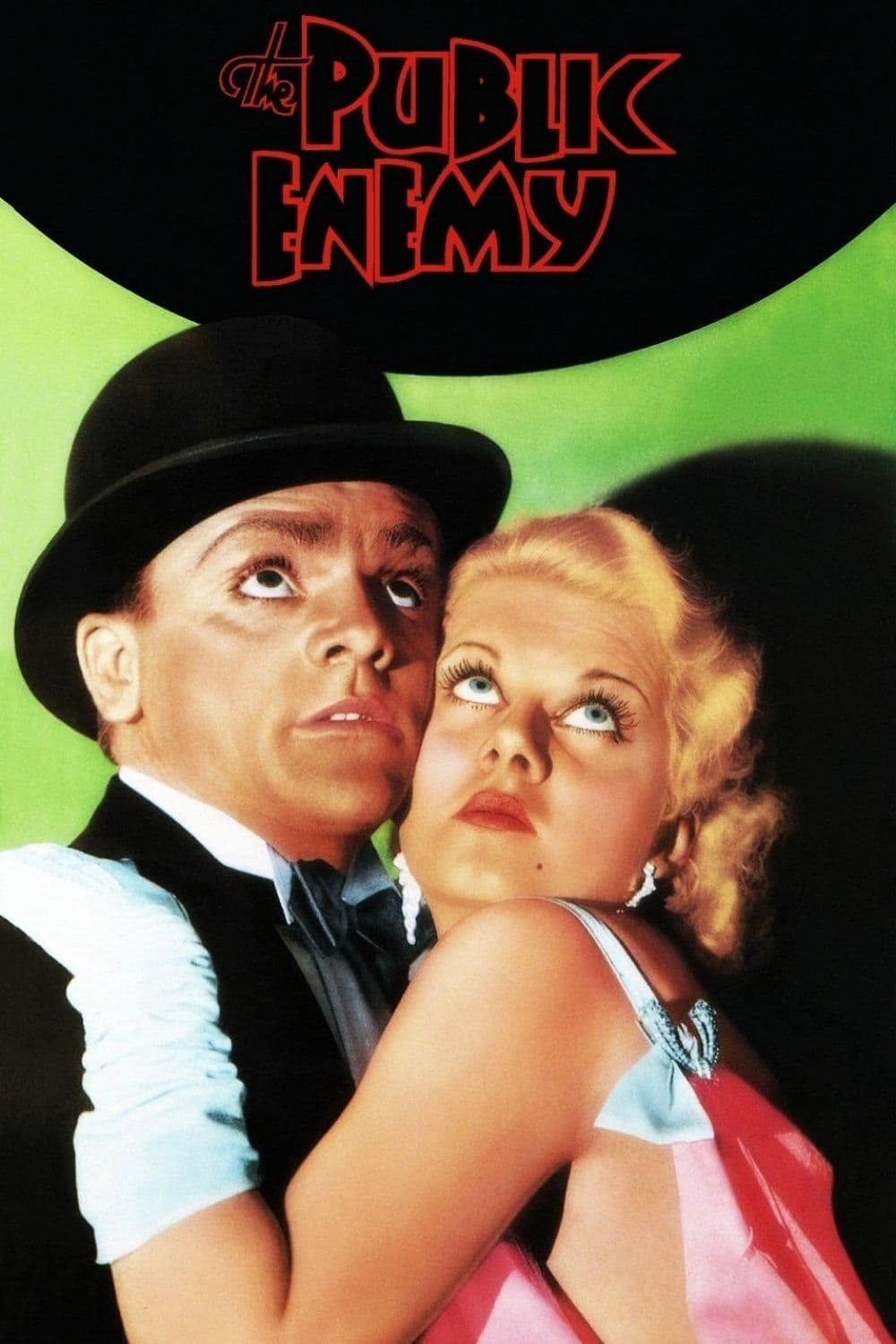

The Public Enemy

1931

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Wellman’s 1933 work remains in some respects unsurpassed in terms of expressive vigor and narrative force. In an era when cinema, still nascent in its sound dimension, audaciously explored the limits of representation, Wellman distinguished himself with a nervous, almost feverish direction that reflected the frenzy and brutal disillusionment of Prohibition-era America. The film, with its explicit violence and ambiguous portrayal of the gangster's role, provoked controversy and censorship, but was an enormous public success, profoundly influencing American and international cinema. This narrative and visual daring was possible thanks to the climate of pre-Code Hollywood, an ephemeral period of creative freedom before the rigorous enforcement of the Hays Code castrated many of cinema's rawer and morally ambiguous expressions. The Public Enemy, in this context, became a true manifesto, a wild shard that tore through the veil of bourgeois hypocrisy, forcing the viewer to confront an unsettling and fragmented reality. The rest was done by Cagney with his extraordinary mimetic talent combined with an undeniable physique du rôle, a perfect alchemy between explosive charisma and a subtle, almost chilling, menace. His performance was not merely acting, but a visceral embodiment of indomitable energy that fused the archetype of the "street tough" with the titanic figure of the modern outlaw, clearly distinguishing him from the more statuesque and less dynamic interpretations of colleagues like Edward G. Robinson or Paul Muni.

The story is that of the rise and fall of an urban gangster: Tom Powers in the tumultuous America of the early 20th century, when Prohibition marked a Manichaean watershed between legality and the criminal underworld. It was the era of the "Roaring Twenties," a decade of prodigious economic expansion and deep social fractures, where the American dream seemed within reach for a few, while many others, excluded from the system, found in organized crime a distorted but seductive path to wealth and power. This context of ferment and social injustice became the primordial soup in which the figure of the gangster as an anti-hero flourished, a rebel against an authority perceived as corrupt and hypocritical. Inspired by the true stories of gangsters like Al Capone, the narrative follows Powers' journey, from a difficult childhood on the streets of Chicago to his ascent to power in the world of organized crime, a trajectory that is not merely a chronicle of criminal escalation, but also a raw sociological analysis of the forces that shape such a destiny. Tom, along with his friend Matt Doyle, engages in robberies and illegal dealings, clashing with rival gangs and law enforcement, in a world where fraternal loyalty is as vital as it is ephemeral, destined to crumble under the weight of violence and betrayal. Wellman, with a compelling narrative rhythm and visually impactful scenes, shows the violence and brutality of the criminal underworld, but at the same time reveals its allure and seductive power, an ambivalence that makes the audience complicit and terrified, caught in a whirlwind of admiration and repulsion. Tom Powers, thanks to a Mephistophelian James Cagney, is a character characterized by explosive energy and disarming cynicism, which makes him both repulsive and fascinating. Emblematic of this duality is the now legendary scene in which Cagney, with a gesture of brutal and sudden assertion of power, smashes a grapefruit into his girlfriend's face: a moment of pure and shocking misogyny that, far from alienating the viewer, reveals his magnetic and disturbing stage presence, a daring unthinkable after the Hays Code came into effect, which would have imposed a facade of morality. Also famous is the bloody scene where Cagney, with a machine gun, targets one by one, hitting them with his enigmatic gaze even before the bullets, a sequence of pure kineticism that foreshadows the choreography of violence that would become a hallmark of action cinema.

In The Public Enemy, violence is not just a narrative element, but a true language, an expressive medium that Wellman uses to address his audience, a desperate and disillusioned cry about human nature and the society that corrupts it, condemning but at the same time investigating the roots of evil. With its raw and realistic portrayal of the criminal underworld, the film established many of the canons of the Gangster Movie: the rise and fall of a charismatic but ruthless gangster, a tragic parable often culminating in a bitterly ironic ending, with death as the only escape from a life of excess and fear; explicit and stylized violence, never gratuitous, but always functional in highlighting the brutality of a world without redemption, where every act of force has a tangible and often fatal consequence; the degraded urban setting, a metropolitan landscape that is not merely a backdrop, but a character in itself, a labyrinth of dark alleys and dilapidated neighborhoods that swallows its children and shapes their destiny; the conflict between rival gangs and law enforcement, an eternal struggle between two sides of the same coin, chaos and apparent order, where moral boundaries often blur; the protagonist's moral ambiguity, often a tragic anti-hero whose reprehensible conduct is mixed with glimpses of a distorted humanity or a perverse code of honor; and the use of a dynamic and innovative visual language, consisting of audacious shots, tight editing, and expressionistic lighting that anticipates Film Noir and gives psychological depth to the figures. The film profoundly influenced American and international cinema, inspiring generations of filmmakers and helping to define the gangster archetype in popular culture. It is no coincidence that directors like Francis Ford Coppola drew upon its family epic and almost Shakespearean solemnity in The Godfather, elevating the criminal saga to a Greek tragedy. Or that Martin Scorsese assimilated its visceral quality and melancholic fascination with "small-time" street criminals, painting a vivid and often painful fresco of life on the margins in works like Goodfellas. Brian De Palma reinterpreted its stylization of violence in an operatic and baroque key, while Quentin Tarantino, even while deconstructing the genre through postmodern quotation and irony, absorbed its lesson on the power of dialogue and the twisted charisma of its characters. The Public Enemy is not just a film, but a true archetype that, traveling through time, became embedded in the imagination of directors and screenwriters, providing them with the syntax and lexicon to define the concept of the Gangster Movie. An experience that shortly thereafter would then evolve into that splendid spin-off known as Film Noir, a natural evolution of the gangster genre that, transcending mere criminal chronicle, delved into the psychological and moral intricacies of the individual, enveloping its stories in an atmosphere of bleak fatalism and existential ambiguity. In this new universe, shadows extended not only over the city streets, but over the very soul of its ill-fated protagonists, and the "femme fatale" often replaced the figure of the loyal companion, bringing an even more lethal dimension of seduction and betrayal, while violence, though still present, became more cerebral, less explicit, but no less devastating in its psychological implications.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...