The Quiet Man

1952

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Ford directed this film as an unconditional act of love for his country of origin: Ireland. It was not merely an artistic whim or a deviation from his established path in the Western genre, but a true personal epic, a desire nurtured for decades since the 1930s, when attempts to bring Maurice Walsh's story "Green Rushes" to the screen encountered logistical hurdles and production resistance. For Ford, the son of Irish immigrants, the idealized return to the land of his ancestors through the camera was a spiritual pilgrimage, a way to reconnect with deep, never-severed roots, though often hidden behind the mask of the gruff, quintessentially American director.

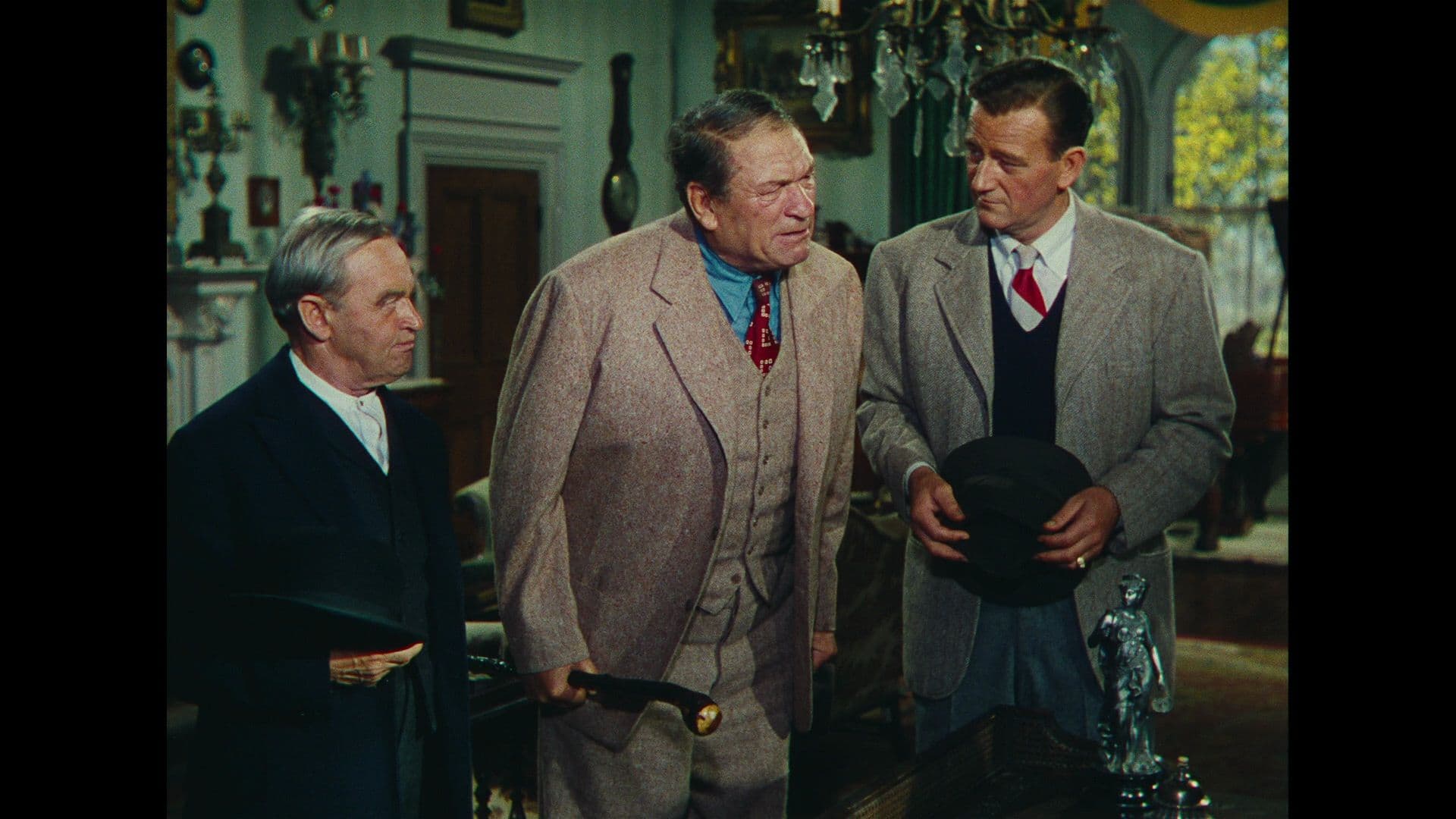

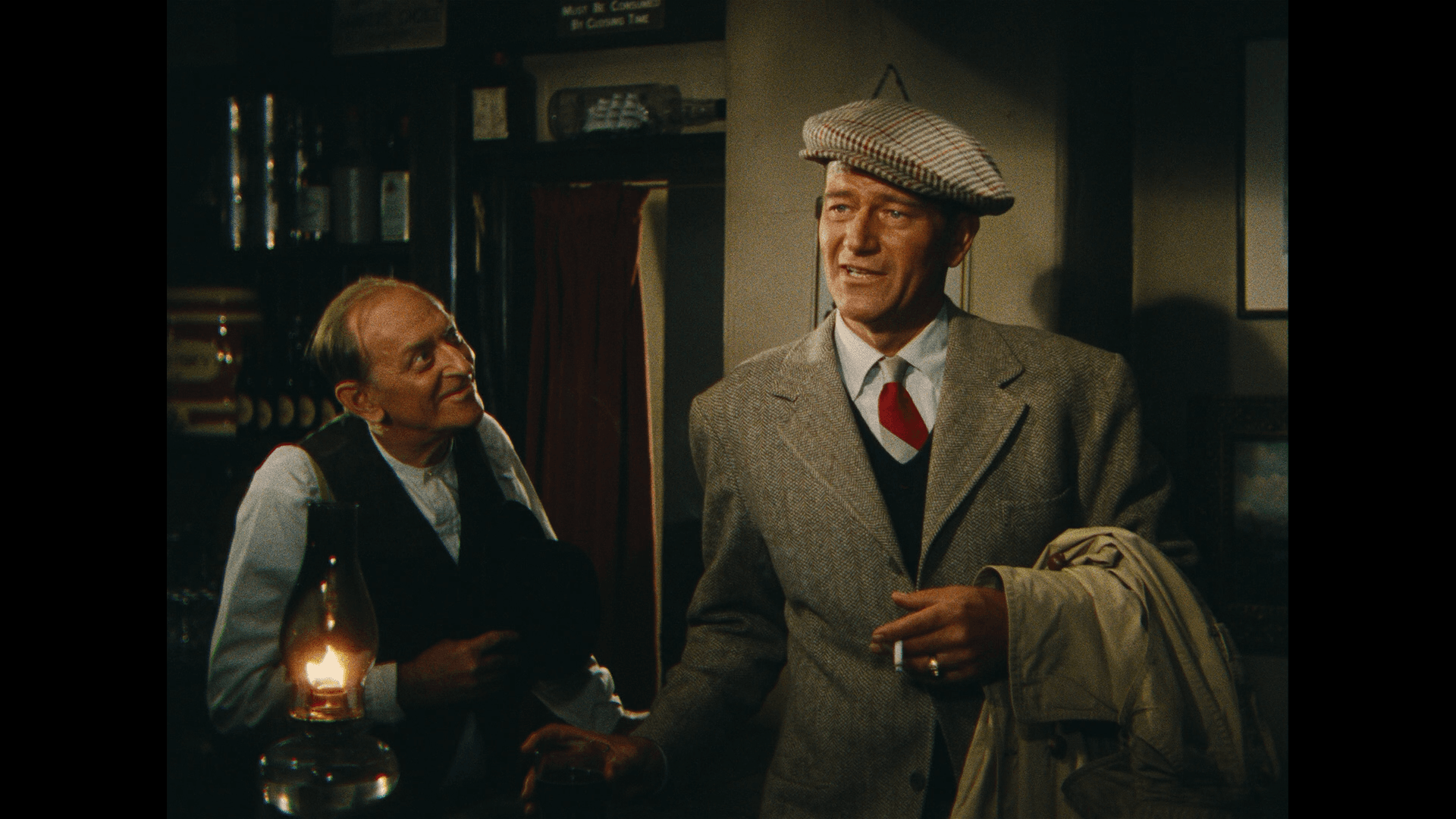

To do so, he brought along his favorite actor, John Wayne. Here, however, "the Duke" is not the indomitable pioneer or the solitary prairie rider, but transforms into Sean Thornton, an American boxer marked by pain and seeking redemption, who wears tweed and clashes with the peculiarities of a rural Irish community. It is one of Wayne's most tender and vulnerable performances, a multifaceted portrayal that reveals his unexpected ability to convey shyness, contained anger, and love with a delicacy that transcends his imposing stature. Through Sean, Ford seems to project a part of himself: the powerful man who desires peace and belonging, but must still confront his inner demons and societal expectations.

The result was an emotional work where narrative pathos and aesthetic synthesis are inseparable, giving rise to a film certainly worthy of mention within Ford's filmography. Every shot is a brushstroke of vibrant nostalgia, an ode to the wild beauty and straightforward faces of rural Ireland. Ford does not merely film a landscape; he animates it, makes it a co-protagonist, a character that breathes with its inhabitants, with centuries-old stone walls and green fields fading into the horizon, enveloped by morning mist and kissed by the setting sun. The film is not just a story, but a sensory and cultural experience, a plunge into the soul of a people.

The story is that of an Irish boxer in the States. After the tragic end of one of his matches, in which his opponent dies, he returns to his country of origin. This return, however, is not only geographical but also spiritual. Sean seeks refuge, a tranquility that the noisy world of boxing and the American metropolis cannot offer him. But the Ireland he finds is not that of his childhood memory or fairy tales; it is a living, pulsating land, steeped in traditions and unwritten rules that the outsider (though of Irish blood) struggles to understand. In Ireland, he finds love in the proud and stubborn Mary Kate Danaher, played by a fiery Maureen O'Hara, with whom he shares an explosive chemistry that lights up the screen. But he must once again fight for it, no longer in the ring, but against a series of intrinsically Irish obstacles and impediments: the stubbornness of Mary Kate's brother, Red Will Danaher, the unresolved issue of the dowry, and the cultural misunderstandings between American individualism and the Irish sense of community.

The film progresses in a Rossinian crescendo of misunderstandings, comical and dramatic situations, culminating in one of the most memorable and prolonged brawls in cinema history. This is not a mere fight, but a cathartic ritual, a ballet of honor and reconciliation that involves the entire community, uniting Sean and Red Will in a manly and liberating embrace, finally sealing Sean's integration and the triumph of love. It is a triumph of life, folklore, and humanity.

A film in which Ford's hand is poetically inspired in capturing the places of his origins, and in which John Wayne embodies everything the old bandaged lion would have wanted to be. Ford, notoriously, considered this film an anomaly, a "vacation" from his tougher Westerns, but in reality, it is one of his most revealing works, a deep investigation into identity and belonging. The direction is a true act of visual love, with panoramas that capture the vastness and intimacy of the landscape of Cong, Connemara, making us feel part of that picturesque and at times magical world.

Interesting is the use of color, which forced Ford to reconsider some of his signature techniques (like long takes) to adapt to the new expressive medium, giving rise to a new way of approaching narrative compared to the black-and-white Western pattern, opening up a new and more mature style for the director that would find its full realization in "The Searchers". The adoption of Technicolor here is not a mere addition of vibrancy, but a crucial narrative and stylistic element. The emerald green of Ireland, the flaming red of Mary Kate's hair, the warm colors of pub interiors and cottages, are not merely decorations; they contribute to creating an almost fairy-tale atmosphere, elevating reality to myth. Ford, accustomed to the monochromatic nuances of the West that emphasized drama and solitude, finds himself here painting with a rich and bold palette, learning to exploit the depth and saturation of color to bring every detail to life, transforming the landscape itself into a vibrant and present character. This chromatic and compositional exploration laid the groundwork for the visual mastery he would later achieve with The Searchers, where color is no longer just beauty but a vehicle for isolation and ruthless vastness, demonstrating how Ford knew how to shape cinematic language to express the most intimate nuances of the human soul and the land that hosts it, be it romantic Ireland or the implacable West. "The Quiet Man" thus remains a luminous gem in his oeuvre, a testament to his versatility and his love for storytelling, imbued with warmth, humor, and a deep, intangible poetry.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...