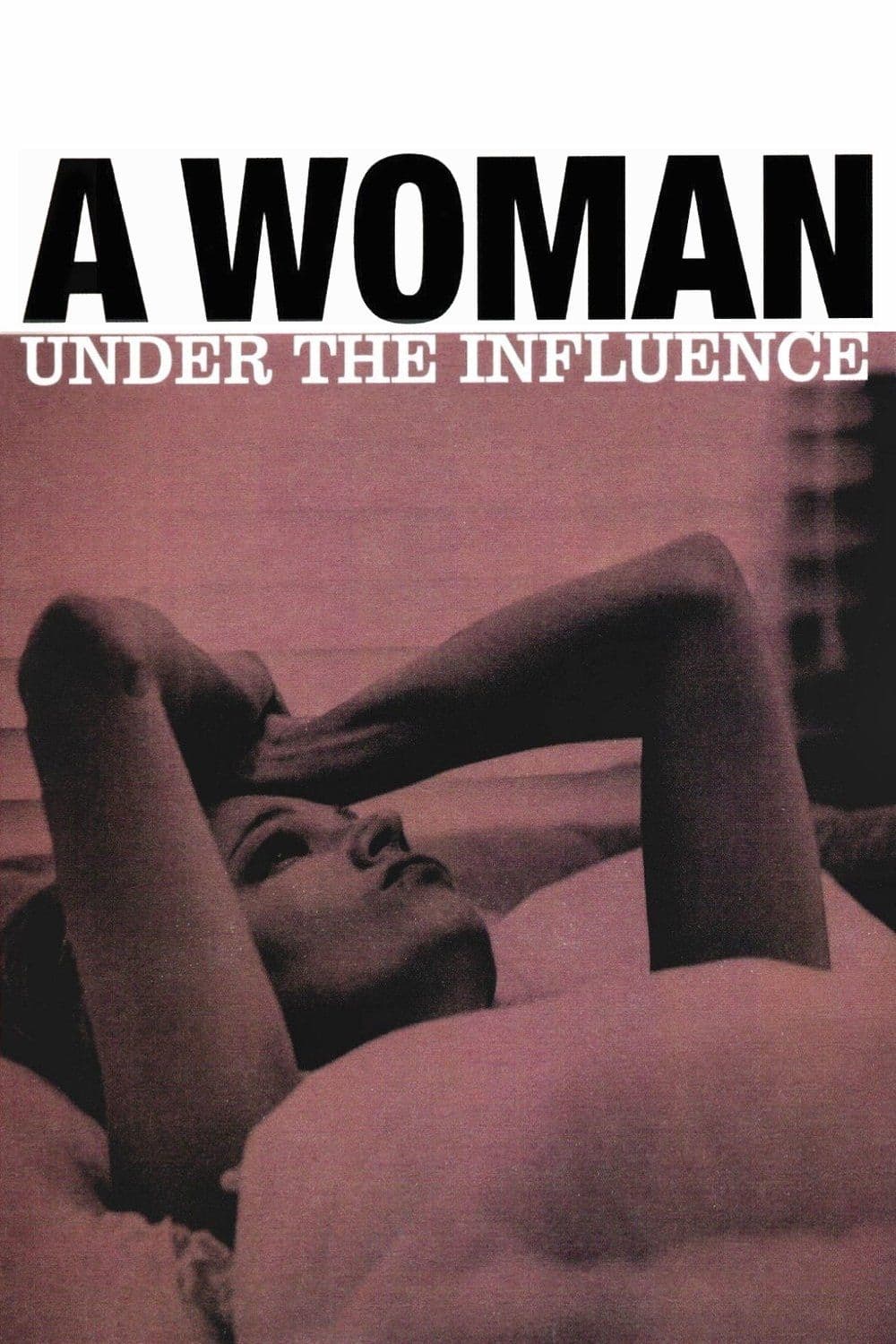

A Woman Under the Influence

1974

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Let's face it, John Cassavetes is perhaps the most underrated director in the entire American cinematic landscape. Not just a niche assertion, but a stark realization for a filmmaker who, long before the concept of "independent" became a marketing label, carved out his vision with a consistency and emotional brutality that few others have matched. His was a constant struggle against Hollywood conventions, a relentless pursuit of human truth through the exploration of the ordinary, imperfections, and psychological nuances that the great American dream machine preferred to conceal. Cassavetes, a spiritual father of an American cinema verité that anticipated trends and languages, is an authentic precursor, whose influence still resonates today in the works of directors dedicated to the rawest and most visceral authorship.

Already an actor in Rosemary’s Baby, where his stage presence helped weave the murky psychological substratum of Polanski’s masterpiece, he later became the author and director of wonderful films like “A Woman Under the Influence,” a bitterly ironic title that the Italian distributor cheerfully decapitated into a title with only the subject, "Una Moglie" (A Wife). This seemingly innocuous translation choice, however, actually betrays the complex ambiguity of the original title: "A Woman Under the Influence" evokes not only a state of psychic alteration but also the influence exerted by a suffocating society, by marital expectations, and by the pressure to conform to an ideal of woman and mother. The omission of "Under the Influence" strips the film of one of its most powerful interpretative keys, reducing a multi-layered work to a mere chronicle of an existence. It is a film that perfectly fits into his filmography, consistent with the explorations of human fragility already visible in works like Faces or Minnie and Moskowitz, but which here reaches an almost unbearable intensity.

A work in which psychological deterioration and dialogic aphasia are not just themes but become the very language through which Cassavetes investigates the depths of the human soul. The eye of his camera does not seek easy resolutions, nor clinical pathologies to categorize, but rather the most intimate and disordered manifestations of an existential unease. It is no coincidence that his aesthetic, made of long close-ups, nervous handheld camera, and dialogues that often overlap and fragment, in some ways recalls the unadorned realism of certain Italian Neorealist cinema or the French Nouvelle Vague, but with an entirely American sensibility, less intellectual and more instinctive. The sensation is that of witnessing a domestic tragedy unfolding in real time, without filters or sugarcoating, where the unspoken, awkward pauses, and uncontrolled outbursts reveal more than a thousand speeches.

The two main actors, Peter Falk and Gena Rowlands, are excellent; their chemistry on set is palpable, almost a natural extension of their personal and professional lives – Rowlands was, after all, Cassavetes' wife, an irreplaceable muse and artistic collaborator. This deep understanding, this mutual knowledge that transcended mere acting, allowed them to bring to life characters of disarming complexity. Gena Rowlands is an unforgettable Mabel Longhetti, capable of oscillating between the tenderest vulnerability and bursts of almost animal despair, in a performance that has become a benchmark for female acting. She doesn't merely portray madness, but lives it, breathes it, makes it tangible in every awkward gesture, in every lost gaze. Peter Falk, for his part, doesn't merely portray Nick as a crude and uncomprehending husband but imbues him with a painful humanity, that of a man who loves his family but is completely unprepared to face the emotional abyss into which his wife is falling. Their dynamic is a ballet of love, frustration, compassion, and inability to communicate, a microcosm of many real relationships.

The story recounts the emotional decline of a quiet middle-class American wife, who is hospitalized in a psychiatric facility following a severe depression. The historical and cultural context of the 1970s is fundamental to fully understanding Mabel's drama: an era in which middle-class women were still chained to predefined social roles, where the "perfect housewife" was the only acceptable model and any deviation from it was seen as pathology. Mabel is not "mad" in the clinical sense of the term; she is perhaps too sensitive, too alive, too authentic for a world that demanded her to remain silent, composed, invisible. Her crisis is a distorted and painful cry for liberation against the golden cage of domesticity, a scream that resonates with the first, timid stirrings of the feminist movement, when female existential unease began to be politicized and recognized.

Upon her return, she will try with all her might to reclaim her family but will find a radical change in her husband, or perhaps in herself. This ambiguity, "or perhaps in herself," is Cassavetes' stylistic signature: there are no easy answers, no single culprit. Change is intrinsic to human nature, to pain, to the attempt to survive. The film categorically rejects any external psychological diagnosis, focusing instead on the lived experience of mental illness within a family unit, pushing the viewer to confront the irrational and the unspoken.

She will also have to contend with her own dislocation from the surrounding world; society seems to become an impending threat, and a bleak alienation from everything hovers within her. This "alienation" is not merely internal; it is a reaction to a world that judges her, that does not understand her, that wants to bring her back to a "normality" which for her is a prison. Society, with its implicit norms and suffocating expectations, becomes the true antagonist, an invisible yet omnipresent force that pushes her further and further to the margins.

Her three children will help her in the endeavor to rediscover a human dimension. The children, in their innocence and their disarming ability to accept their mother for who she is, without judgment, represent Mabel's only true lifeline. They are the only ones capable of seeing beyond her "madness," of perceiving the fragility and love hidden behind her most disconcerting gestures. Their unconditional love, their small hands reaching for her, their voices calling her, are the only lighthouse in an ocean of disorientation.

Psychological introspection is pushed to the highest level, creating a sort of narrative tunnel between character and viewer. Cassavetes doesn't just show us Mabel's story; he makes us live it. Through his almost documentary style, the handheld camera that follows every breath, every tic, every outburst, the viewer is catapulted into the intimate depths of the protagonist's psyche. We become involuntary voyeurs of her suffering, uncomfortable witnesses to a drama that envelops and shakes us, making it impossible to look away. It is a cinema that offers no escape, but compels empathy and reflection.

Cassavetes places this woman's emotions and thoughts into our hands, transforming her into a crystal doll in which every single impulse can be distinguished. A "crystal doll" not only for her fragility and emotional transparency but also for the constant threat of shattering into a thousand pieces, for her existential precariousness. Hers is a raw and unvarnished performance, where every nerve is exposed, every emotion brought to the surface with brutal honesty. Mabel is exposed, vulnerable, and in this vulnerability lies all her unsettling, unforgettable humanity.

A film dense with repressed anger but also melancholic sweetness, a work that leaves no one indifferent, that gets under your skin and continues to provoke thought long after the credits roll. "A Wife" is not just a film about mental illness, but a deep exploration of the human condition, the limits of communication, love, and loneliness. A masterpiece that leaves a lasting impression, a punch to the gut and a hug at the same time, and which confirms Cassavetes as one of the greatest investigators of the human soul ever to appear on the silver screen.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...