Vertigo

1958

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Vertigo is first and foremost a highly sensitive probe into human fears, a profound journey into the most recondite folds of the human psyche, where obsession, loss of control, and the annihilation of identity manifest with an almost unbearable force. It is not only physical vertigo that dominates the scene, but an existential vertigo that grips the protagonist, John "Scottie" Ferguson, and with him drags the viewer into an unparalleled emotional abyss.

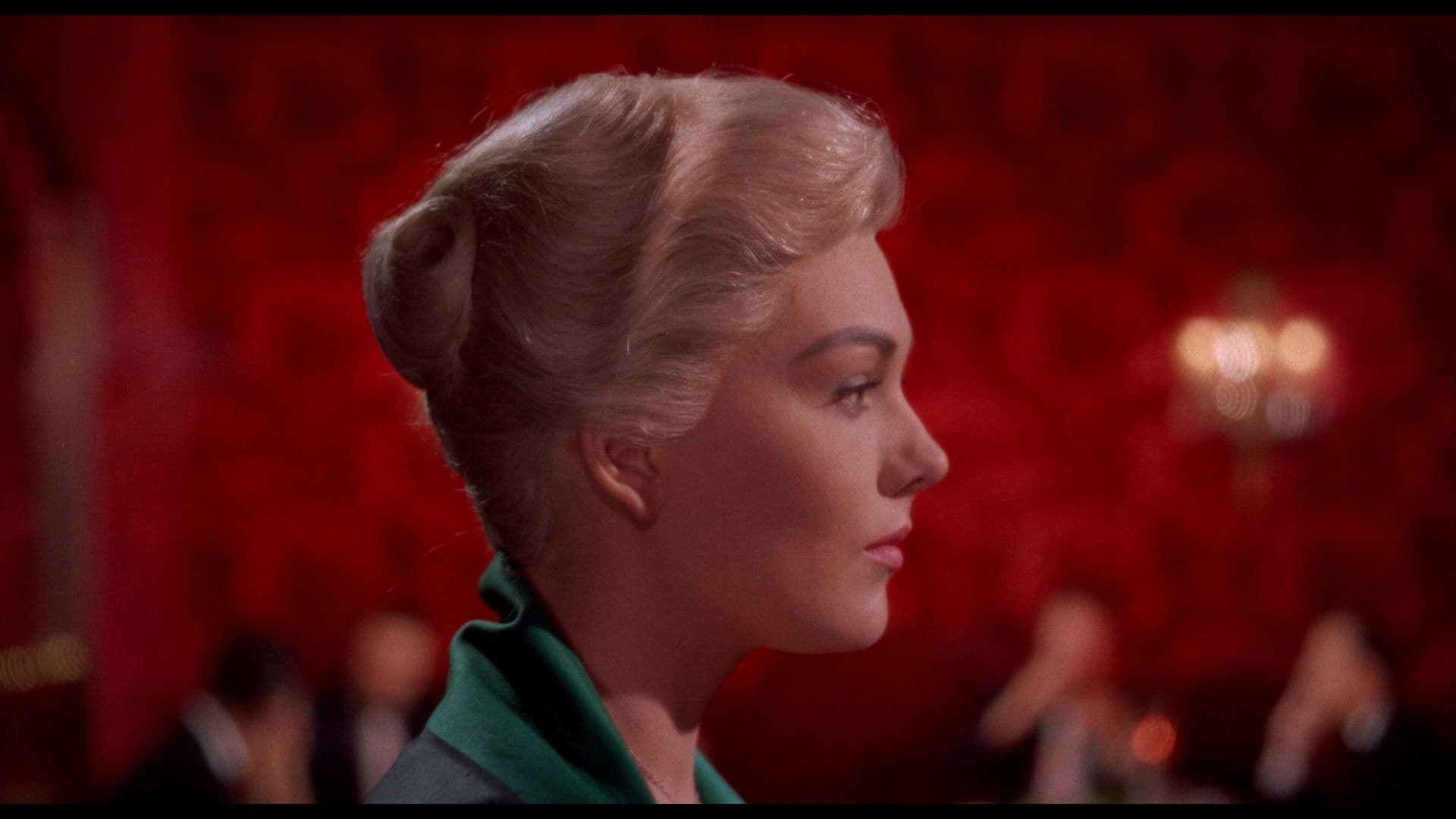

It is undoubtedly a work of immense artistic value that gains even more visual power thanks to the way Hitchcock manages to capture the vibrant emotions of every character involved in this story on film. His genius lies in his ability to transfigure the invisible, the uncanny of the subconscious, into a cinematic language of disarming power. We think of the color palette, particularly the spectral green that envelops Madeleine, almost suggesting her ethereal and ghostly nature, or the iconic spirals that repeat obsessively, from the staircases to Kim Novak's hair curl, a visual symbol of paranoia and the downward spiral into which Scottie plunges. To this is added Bernard Herrmann's musical score, a masterpiece in its own right, whose poignant and pervasive notes blend with the images, elevating the sense of fatalism and morbid romanticism to unattainable heights. It is a symphony of anguish and desire, a sound commentary that digs into the soul as much as the images themselves.

The plot features a San Francisco detective, tormented by acrophobia and guilt, hired by a woman's husband to follow his wife and investigate her mental state. It will be the opportunity for the man to sink into a spiral of paranoia and mystery, but also into a self-imposed prison of unattainable desire. Scottie, initially an external observer, a voyeur by profession, soon becomes the object and subject of a consuming obsession, transforming him from hunter to prey, not of a criminal, but of his own distorted psyche. The city of San Francisco, with its steep hills and elegant neighborhoods, becomes almost a character in itself, an urban labyrinth reflecting the labyrinthine complexity of Scottie's mind.

Hitchcock's most perverse art is to make us partake – gradually but inexorably – in the protagonist's phobias, but always in a state of suspension, as if to give us time to ask: is all this real? A cruel game played out on the viewer, then, Hitchcock's favorite pastime, which makes us complicit in an act of voyeurism and manipulation. When the truth is revealed midway through the film, in a gesture of narrative audacity that disoriented not a few critics at the time, the mystery gives way to a psychological tragedy of rare intensity. It's no longer about "who did it?", but "why is he doing it?" and "how far will he go?". The focus shifts from external intrigue to internal torture, transforming the thriller into a profound investigation into the male desire for possession and the dissolution of female identity. The scene of Judy's transformation into Madeleine, where Scottie molds and recreates the object of his desire with almost maniacal precision, is a cinematic pinnacle on the nature of projection and emotional necrophilia, an unsettling exploration of the Pygmalion myth inverted into its darkest side.

But Vertigo is also a love story, and this is its great narrative mastery: that of making the two genres – thriller and romantic – march in perfect synchrony, then blending everything into a classic Shakespearean tragedy. Not an idyllic love, but rather an obsessive and self-destructive passion, a necrophilic obsession for a ghost, a man's desperate attempt to resurrect an illusion, to control and reshape the beloved woman in his own image, or rather, in the image of another. It is the drama of unfulfilled desire, of memory that deceives, of solitude that corrodes. Love here is a form of imprisonment, for those who experience it and for those who are its object, a morbid bond that inevitably leads to catastrophe. The film foreshadows themes that would be revisited by subsequent directors, such as Brian De Palma or David Lynch, in their exploration of the dynamics between identity, representation, and desire, consolidating its status as a seminal work.

A negative mention for the Academy which, in awarding the Oscars in 1958, overlooked both this film and Welles' Touch of Evil, a true travesty that film history has largely corrected. At the time, Vertigo was met with a certain coolness by critics, perhaps too far ahead of its time, too complex in its structure, too uncomfortable in its analysis of human perversions. It didn't even receive a nomination for Best Director or Best Picture. Yet, over the decades, its status has grown exponentially, to the point of being crowned as "The greatest film of all time" in Sight & Sound's decennial poll of 2012, even surpassing Citizen Kane. This reversal of judgment testifies to its inexhaustible depth, its ability to continue to interrogate and fascinate generations of viewers and scholars, always remaining a step ahead.

Vertigo: a prolonged cinematic thrill, masterful direction that draws emotional architectures even before physical ones, an irreplaceable film that continues to unveil new depths with every viewing, demonstrating its timeless power as an investigation into obsession, loss, and the illusory nature of reality. It is a cinematic monument to the fragility of the human mind and the perennial search for what cannot be grasped.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...