A Streetcar Named Desire

1951

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Elia Kazan adapts Tennessee Williams' poignant stage drama to film.

The result is a powerful and intense film, superbly acted and with a truly worthy dramaturgical adaptation. The work stands as a monument to 20th-century American dramaturgy, a relentless portrayal of the human condition where fragile illusions clash with the inescapable brutality of reality.

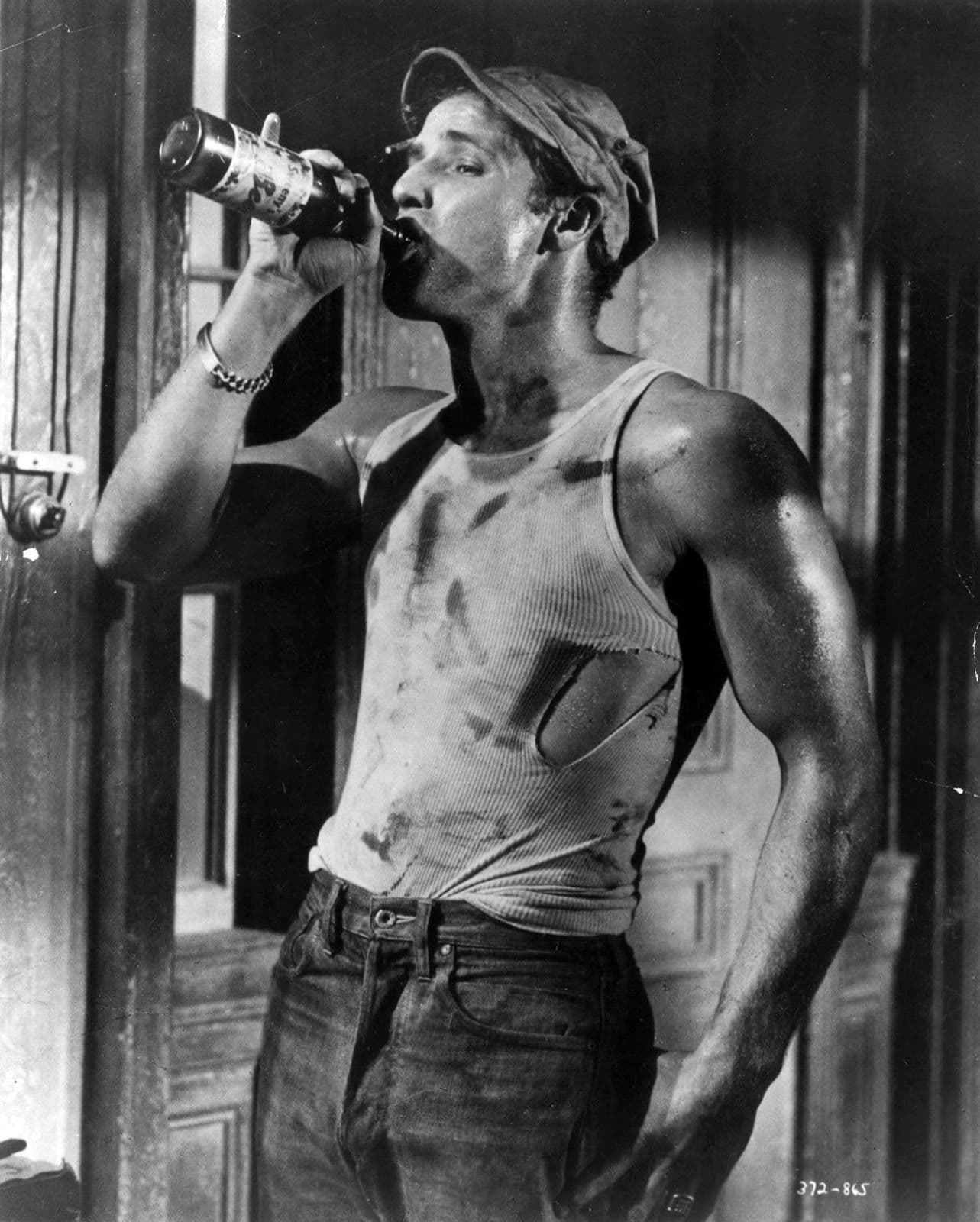

The story centers on Blanche DuBois, a neurotic Southern woman, representing a twilight and dying civilization, who, fleeing a past of scandals and despair, intertwines her destiny with that of her sister Stella and Stella's husband, Stanley Kowalski. This three-way dynamic translates into an anatomy of human passions, brought first to the stage and then to the big screen, which does not alter the aesthetic and speculative essence of the work at all. Indeed, the conflict between Blanche's ethereal and artificial world, woven from lies and decadent poetry, and Stanley's crude, primordial virility, an icon of a post-war America in full ascent and unembellished, acquires an almost mythological resonance on the big screen. Williams, with his unparalleled mastery, paints a fresco of sexual repression and forbidden desire, of mental decay and latent violence, all filtered through a naturalism imbued with lyrical symbolism that Kazan manages to capture in every nuance. The claustrophobia of the Kowalskis' apartment, a suffocating microcosm steeped in humidity and sweat, becomes the theater of a no-holds-barred psychological battle, a true Freudian essay on the soul's darkest impulses.

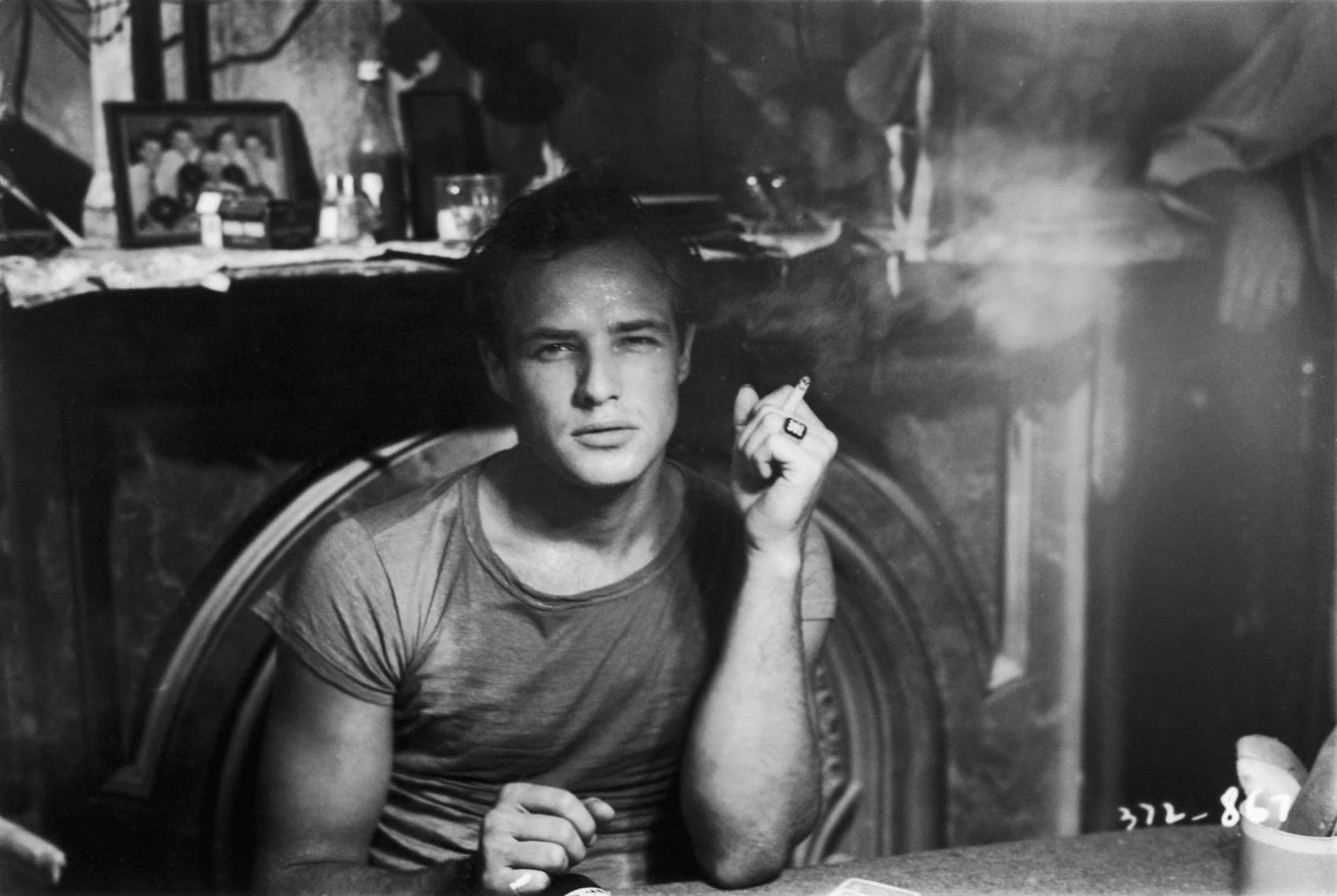

Kazan's ability to preserve the purely theatrical essence of the work, conceived for the stage, is remarkable; the director intelligently maintains the dialectical fluidity of the dialogues and the almost entirely indoor setting (with the exception of a few exterior scenes shot in New Orleans). But his mastery goes far beyond simple faithfulness: Kazan, trained at the Actors Studio and a master of the nascent Method acting school, uses the camera not just to document, but to amplify. The expressionistic use of light and shadow, indebted to film noir techniques, transforms the apartment not only into a physical prison but into a psychological trap, where the atmosphere becomes increasingly oppressive and the characters' fate seems already sealed. The insistent close-ups on sweaty, tense faces, Harry Stradling Sr.'s dark and high-contrast cinematography, and Alex North's jazzy and melancholic score (whose compositions for the film were among the first in American cinema to significantly incorporate jazz elements) contribute to creating a sensory experience that transcends mere theatrical reproduction. This is particularly evident in the construction of Stanley Kowalski's character, portrayed by a very young and explosive Marlon Brando, whose raw, visceral, and unashamedly sexual performance redefined the canons of cinematic masculinity. His stage presence, composed of grunts, animalistic postures, and an almost brutal impudence, was an earthquake for the era and influenced generations of actors, elevating "The Method" to the dominant stylistic element in Hollywood.

The relationship between the stage piéce and the cinematic version was so close and binding that the production decided to hire almost the entire cast of the Broadway theatrical run. However, the rigorous norms of the Hays Code, the set of film censorship guidelines in force in the United States, imposed significant cuts and modifications compared to Williams' original drama. Some of the more explicit references to Blanche's husband's homosexuality, to her excessive promiscuity, and especially to the final sexual violence perpetrated by Stanley, were toned down or left to implicit interpretation, so as not to offend the sensibilities of the audience and the censors. Paradoxically, these constraints pushed Kazan and the actors to greater subtlety, to communicate through glances, gestures, and silences what could not be explicitly stated, thereby amplifying the film's underlying tension and dramatic impact.

With the excellent exception of Jessica Tandy, who played Blanche on stage and was replaced by Vivien Leigh, an actress with greater media appeal thanks to the worldwide success of Gone with the Wind. This substitution was extensively debated, and the actress was, however, initially considered by some to be the weak point and an alien element of the work. However, over the years, her face became so perfectly suited to Blanche's features, embodying her obsession with fleeting beauty, mental fragility, and desperate search for salvation in a world hostile to her. Her performance is a tour de force of lucidity and madness, a descent into the depths of the mind that finds a tragic echo in her own life. Leigh, notoriously afflicted by bipolar disorder, immersed herself so deeply in the character that, fatefully, the performance became a great cause of suffering and problems with personality dissociation. The actress's emotional fragility merged with that of the character, bestowing upon her Blanche a painful and unforgettable authenticity, making her not only a victim of circumstances but a universal symbol of human fragility in the face of life's brutality, leaving the viewer with a bitter taste in their mouth and the realization that, sometimes, the kindness of strangers is the only refuge in a world that has lost all compassion.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...