Au Hasard Balthazar

1966

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

A film as harsh and piercing as a bullet, terrible in its pessimistic vision of reality, fascinating in the directorial approach Bresson imparts to it, almost as if laying bare a cruel, stepmotherly reality through a shower of stripped-down, raw, overtly real images, with stark and crystalline cinematography shrouded in opalescent black and white. Bresson does not merely frame, but chisels the image and sound with almost maniacal precision, purifying them of any theatrical redundancy to arrive at the essence of the modèle, that peculiar non-actor who, for the French director, is a pure instrument of revelation. His "stripped-down images" are not devoid of life, but emptied of all artifice, capable of becoming a vessel for a naked and raw truth which, in his view, conventional acting would tend to obscure. It is the triumph of pure cinematography over the artifice of cinéma, where every gesture, every sound – the tinkling of a bell, the screech of tires, the heavy silence – takes on a specific gravity, revealing an inner world that denies mere psychological representation.

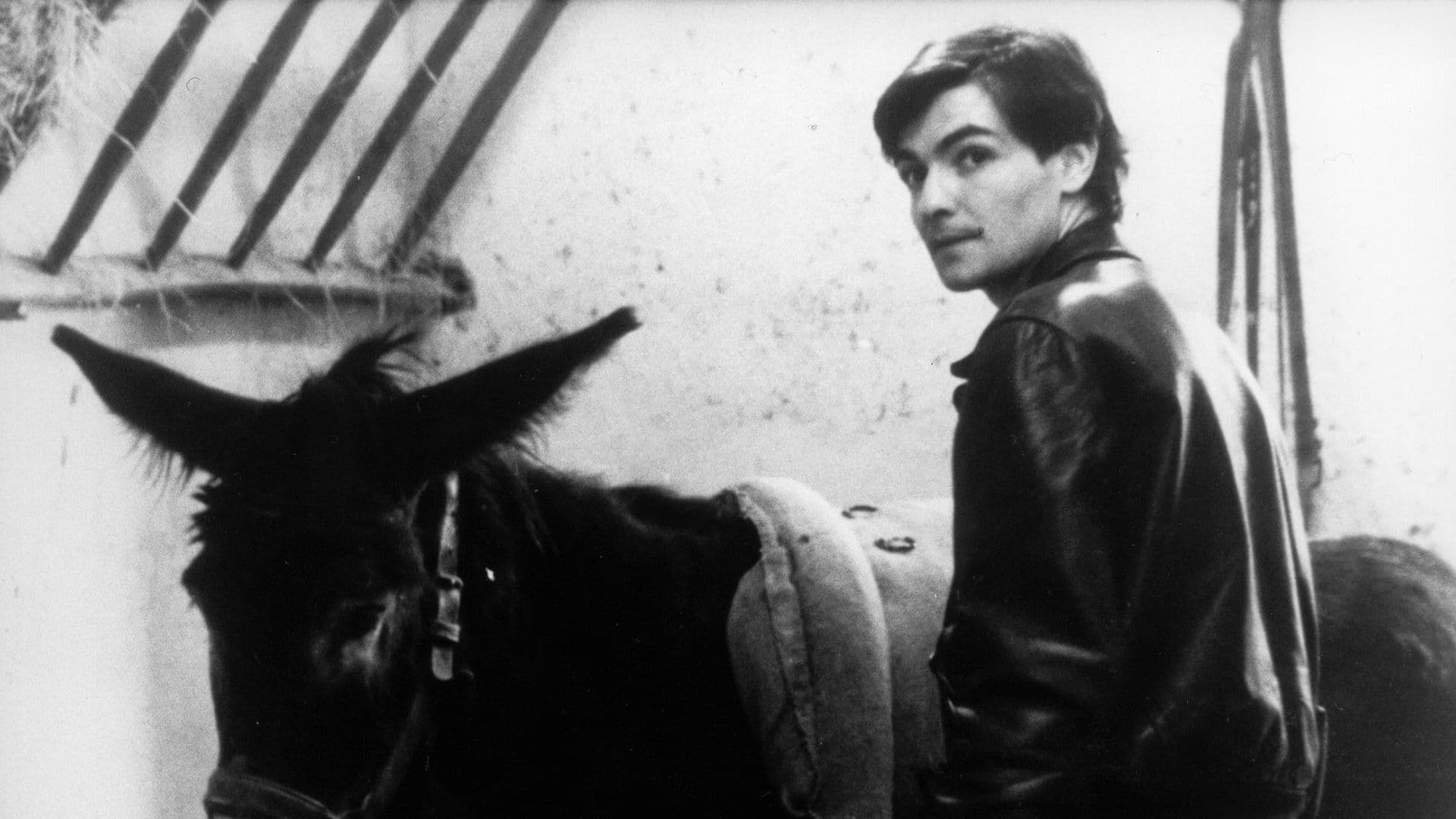

The protagonist of this story is a donkey named Balthazar; at first, he is raised by Marie with love, then sold by her father. His ordeal through a hostile land, in the hands of masters who torture him, beat him, annihilate his essence as a living creature. Balthazar is not a mere animal, but the embodiment of innocent suffering, a Christ without a crown of thorns, whose painful path is a metaphor for humanity stained by cruelty and indifference. Every new master he encounters on his path represents a facet of human moral misery: from the miller's greed to the thug Gérard's arrogance, from the priest's false piety to the farmer's mere utility. His impassive gaze, though absorbing the horror, does not judge, and in this passive acceptance of fate lies an almost sacred dignity. His wandering is an allegory of the human condition, an existence marked by an inevitable sequence of predestined events, where grace appears as a fleeting glimmer, almost an illusion, in a world dominated by brutality.

Bresson at his masterpiece, a Leopardian work in its depiction of Nature, yet didactically recalling the lessons of certain Russian narrative like Dostoevsky or Gogol. The connection with Giacomo Leopardi lies not only in the representation of an indifferent and cruel stepmotherly Nature, but also in the painful awareness of suffering as an intrinsic condition of existence, a mal de vivre that permeates every creature. Echoes of "Night Song of a Wandering Shepherd of Asia" resonate in the donkey's silence, heavy with questions, who, though unable to question its own destiny, embodies it with startling expressive power. The lesson of the Russian giants, moreover, is palpable: the examination of human depravity, the search for spiritual salvation in contexts of extreme moral misery, the coexistence of baseness and sublimity, the obsessive investigation into the soul's shadow zones. Bresson shares with Dostoevsky the ability to plumb the depths of good and evil, not through explicit psychology, but by means of actions and reactions that reveal the inner drama.

And speaking of Dostoevsky, it seems Bresson was inspired by him for the subject of this film, having read a passage from The Idiot in which Prince Myshkin, upon arriving in Basel, is woken the next morning by the braying of a donkey "that clears his mind" and immediately reassures him. This anecdote is not merely a philological curiosity, but a profound interpretive key: for Bresson, the animal's purity, its primordial innocence, its ability to exist without pretensions or ulterior motives, becomes a catalyst for the perception of the divine, or at least of the pure. Balthazar, with his mute presence and his acceptance of fate, is a mirror in which humanity can (or should) reflect itself, a being who, like the Dostoevskian donkey, even amidst the world's cruelty, can clarify thoughts, revealing an uncomfortable but essential truth about human nature.

A scene that often resurfaces in memory is Balthazar's baptism by Marie and her brother; the two children bring the little donkey into the house, then sprinkle its muzzle with the water of holiness and let it taste the salt of wisdom. The donkey seems to prefer the wisdom. This inaugural sequence is of extraordinary symbolic power, a rite of initiation that consecrates Balthazar to a kind of original purity and, ironically, to the ordeal that will follow. It is the last expression of innocence before the donkey is thrown into the vortex of human cruelty. The contrast between the children's ingenuity in attempting to instill spirituality and the brutality of the world preparing to devour Balthazar is heart-wrenching. The "wisdom" Balthazar seems to appreciate is not human wisdom born of calculation or cunning, but perhaps that of a silent acceptance of its destiny, a primordial wisdom that allows it to pass through evil without its essence being corrupted.

Au Hasard Balthazar is a film that breathes the tragic fatalism of Jansenism, a current of thought that deeply influenced Bresson, viewing grace as an arbitrary gift and human nature as intrinsically corrupt. The donkey, a symbol of humility and suffering, becomes a vehicle for this misunderstood grace and its denial. The film, despite its apparent narrative simplicity, is a work of extreme philosophical and spiritual complexity, which questions the presence of evil, the possibility of redemption, and the meaning of life in an indifferent universe. Its influence has been enormous, casting a long shadow over directors of the caliber of Michael Haneke or Béla Tarr, who have successfully taken up the legacy of a contemplative, stripped-down cinema, capable of revealing the soul through matter, and which continues to challenge the viewer to confront the most pressing questions of existence.

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...