Band of Outsiders

1964

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Jean-Luc Godard, with his customary aptitude for exploring human impulses, crafts this work in which a trio of characters intertwine their destinies and emotions, in an existential ballet that is as much an homage to cinema as it is a playful deconstruction of it. "Bande à part" belongs to that radiant period of the Nouvelle Vague when the Franco-Swiss director, already established with the iconoclastic "À bout de souffle" (Breathless), continued to disassemble and reassemble cinematic grammar, transforming every shot into a statement of intent. It is not just about human feelings, but about cinematic feelings, about how life imitates art, or vice versa, in a virtuous circle of references and allusions.

Franz and Arthur meet Odile, a young Parisian girl, and begin to court her. A triangle destined never to converge into a single apex, but to float, like the clouds over the Seine, in a perennial emotional uncertainty. Franz is more elegant, with a vaguely melancholic expression, perhaps embodying the trio's more contemplative and, in some ways, tragic soul. Arthur is more dishevelled and carefree, always ready with his jokes to defuse tension, the face of nihilistic carefree abandon, the vital energy that propels action, albeit often aimlessly. Odile, for her part, is an ethereal figure, almost a passive muse, the unwitting catalyst of their adventures, the personification of an innocence still intact yet already faded by the languor of an existence without precise aims. They are not simple characters, but archetypes of a disoriented but intrinsically free youth, moving in a world that no longer offers grand narratives, except those they create for themselves, borrowing them from novels or B-movies.

The three begin to wander through an autumnal Paris in Arthur's Simca convertible, which is a bit like him: run-down and captivating, a dilapidated shell yet capable of holding dreams and escapes. Paris, in Godard, is never a mere backdrop; it is a silent but omnipresent character, both accomplice and spectator, reflecting the protagonists' fluctuating mood. Autumn is not just a season, but a metaphor for an era, that of the early 1960s, when the post-war euphoria began to give way to a subtle existential melancholy, to a sense of emptiness filled by games and make-believe. The Parisian boulevards, smoky bistros, and rain-soaked streets become the setting for a miniature epic, an urban odyssey where boredom is the engine of creativity and crime a mere role-play.

Idly chatting in a bistro, Franz gets the idea to rob Odile's aunt's lodger, a distinguished gentleman who lives in an attic rental and seems to be sitting on a tidy sum. The very idea of the robbery arises not from necessity or genuine criminality, but from a kind of adolescent whim, an awkward emulation of American film noirs so beloved by Godard and his companions from the Cahiers du Cinéma. When the robbery actually happens, of course, everything that could go wrong does go wrong: the house door won't open, the money can't be found, Odile's aunt resists. It is the quintessential anti-heist, a blatant demonstration that these young people are not real criminals, but merely improvised actors on an unlikely stage, whose staging is destined for failure. This fiasco is not a plot weakness, but a pillar of it, a programmatic statement on the emptiness of human endeavours when they lack authentic drive or a real purpose, transforming violence into buffoonery, drama into a comedy of the absurd.

Many things are striking about this film: the voice-over narration that describes the trio's actions and their most secret speculations as if in a novel, a choice that not only adds a literary dimension but also serves as a Brechtian commentary, breaking cinematic illusion and inviting the viewer to a more detached reflection. It is the very voice of the director-narrator, who guides, judges, and at times even contradicts what we see, highlighting the constructed nature of reality and cinema itself. The lighthearted atmosphere, almost like a comedy of errors, contrasts sublimely with the melancholic autumnal backdrop of a Paris never so beautiful, a visual and narrative oxymoron that defines the very essence of "Bande à part."

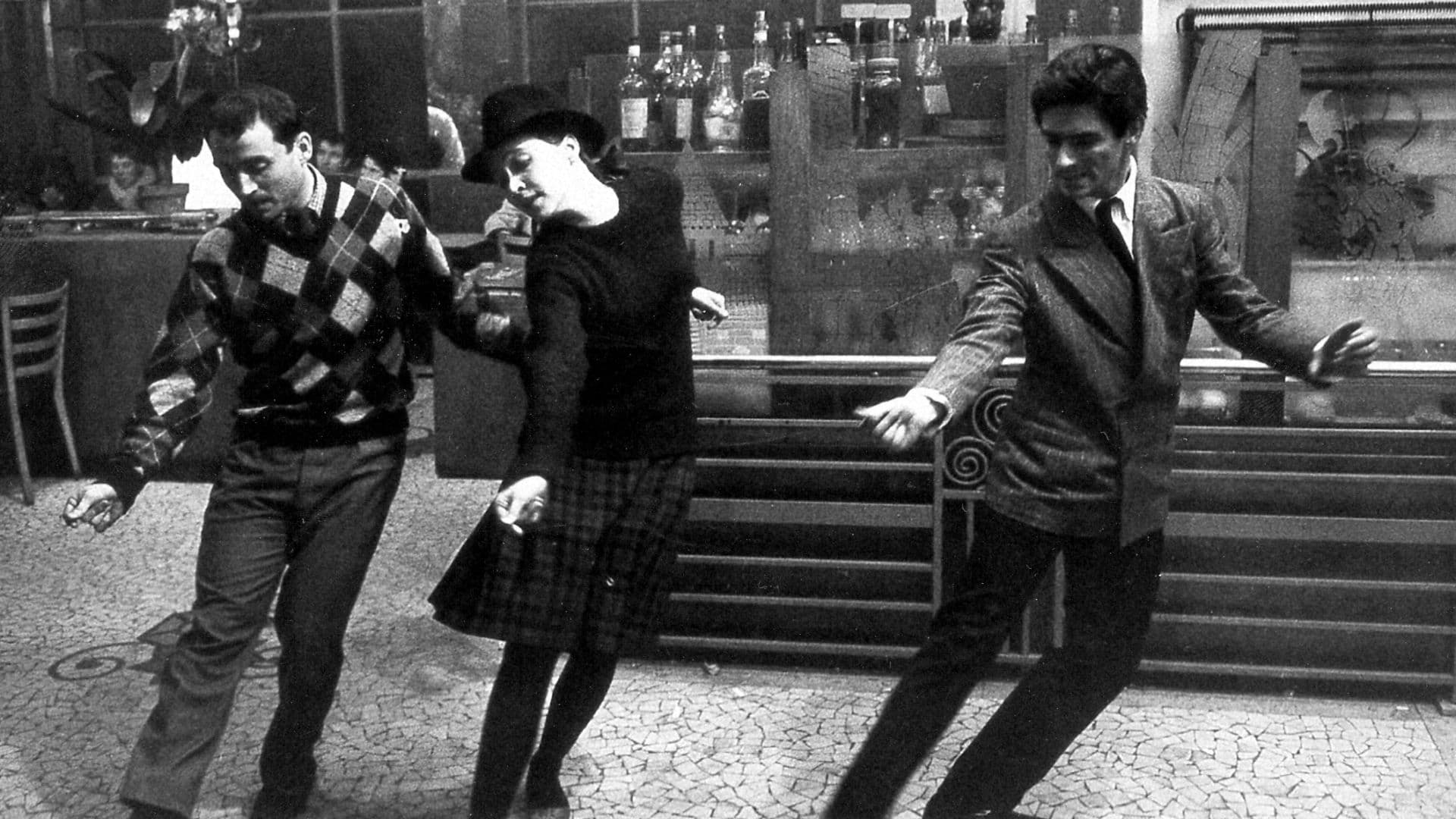

Some scenes, in particular, have entered the collective imagination, true gems of spontaneity and invention. Consider the dance scene in the bistro, the famous "Madison dance": for almost three minutes, the three characters move to the rhythm of ephemeral music, in a moment of pure and almost hypnotic joy, interrupted only by moments of absolute silence, during which the narrator comments on their innermost thoughts. This dance interlude is an explosion of life that crystallizes friendship and lightness, an almost tribal ritual celebrating the present moment, which has become a symbol of the Nouvelle Vague and an inspiration for countless directors, from Bertolucci to Tarantino. Or again, the wild dash through the Louvre's halls to break the museum visit record: a playful act of rebellion against authority, against the seriousness of art and culture, an anarchic burst of youthful vitality that defies conventions and seeks freedom even in the most sacred spaces. It's a race towards nothing, but full of meaning, expressing the thirst for life and for pushing their limits, even if only for an ephemeral personal record. And one cannot forget the mimed street duel between Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid, a brazen and self-referential homage to American cinema, particularly the Western genre. The three friends, playing at being their cinematic heroes, show how deeply popular culture and the Hollywood imaginary had permeated the minds of French youth, transforming daily life into a continuous performance, an imitation of the fictions they loved.

A fresh, sparkling, and refreshing film, like a summer breeze that brings relief on a sweltering day. But it is also a melancholic film, which beneath its veneer of lightness, conceals a profound reflection on solitude, the precariousness of bonds, and the uncertainty of the future. "Bande à part" is not only a hymn to youth and freedom, but also a meditation on their intrinsic fragility, a portrait of an age and an era where carefree living was accompanied by a sense of disorientation. Its "freshness" is not merely stylistic, but stems from its ability to capture an authentic emotion: that of an unnamed anticipation, of a destiny written moment by moment, leaving the viewer with a bittersweet, yet undeniably intoxicating, taste.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...