The Young and the Damned

1950

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A social drama becomes, in Buñuel's hands, a sharp instrument of indictment and at the same time a perfect cinematic mechanism. It is a surgical strike, delivered with the unflinching gaze of an anatomist dissecting the moral and psychological decay festering beneath the veneer of societal order. Buñuel, ever the provocateur, doesn't merely depict poverty; he dissects the very soul-crushing determinism that perpetuates it.

Los Olvidados, or The Young and the Damned as it became known in the Anglophone world, is the third film in the great Spanish director's Mexican cycle and garnered significant recognition, starting with the Palme d'Or at Cannes in '51. This triumph, however, was not universally welcomed. While international critics hailed it as a masterpiece of social realism, its raw depiction of Mexico City's underbelly initially sparked outrage within its home country. Some viewed it as a national disgrace, a betrayal of the idealized image Mexico sought to project to the world, leading to a temporary ban. Yet, it was precisely this unflinching honesty, devoid of any romanticized poverty or convenient resolution, that cemented its legacy and established Buñuel as a formidable voice beyond his surrealist origins. It proved he could master the stark realities of the street with the same subversive power he brought to the dreamscape.

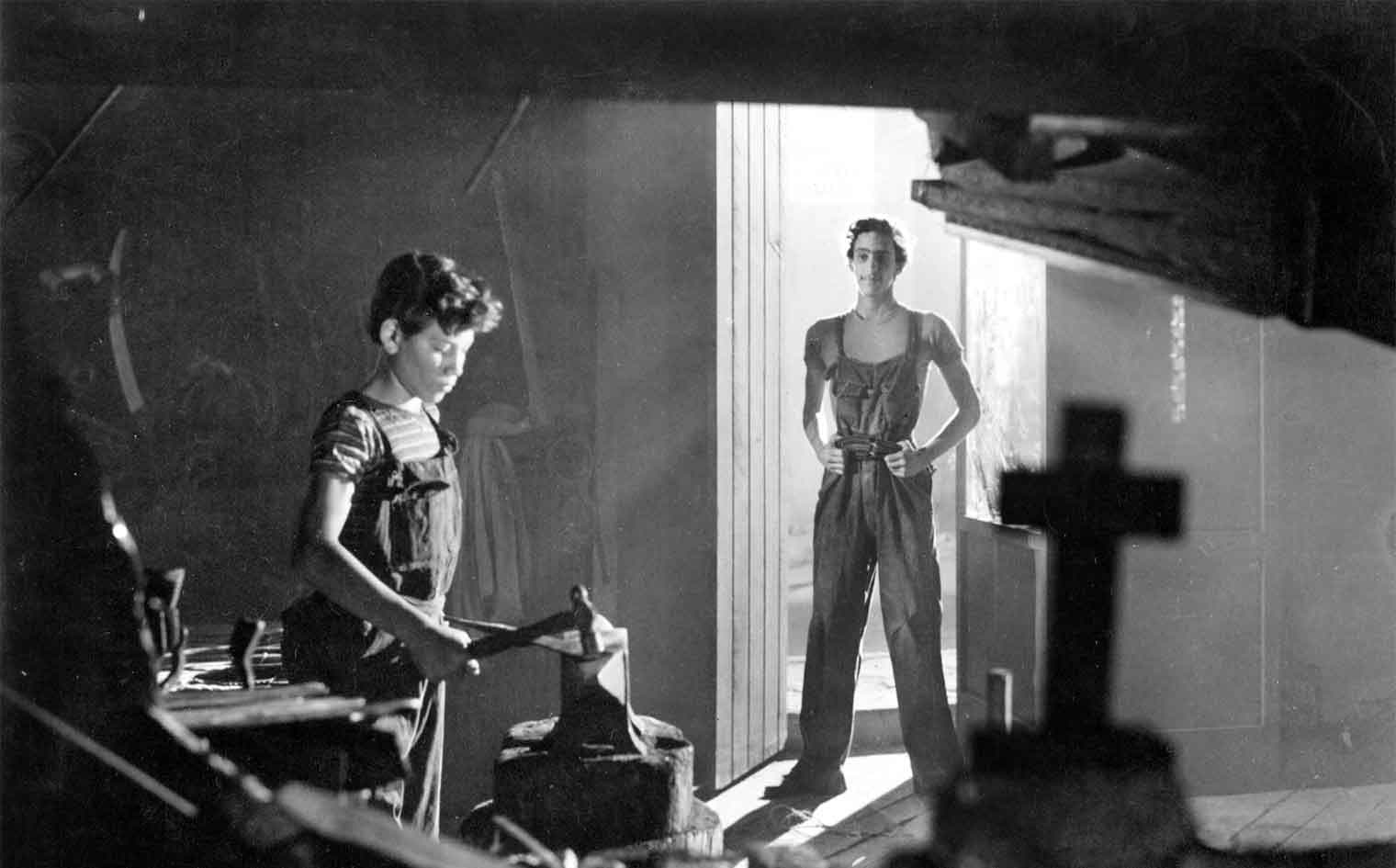

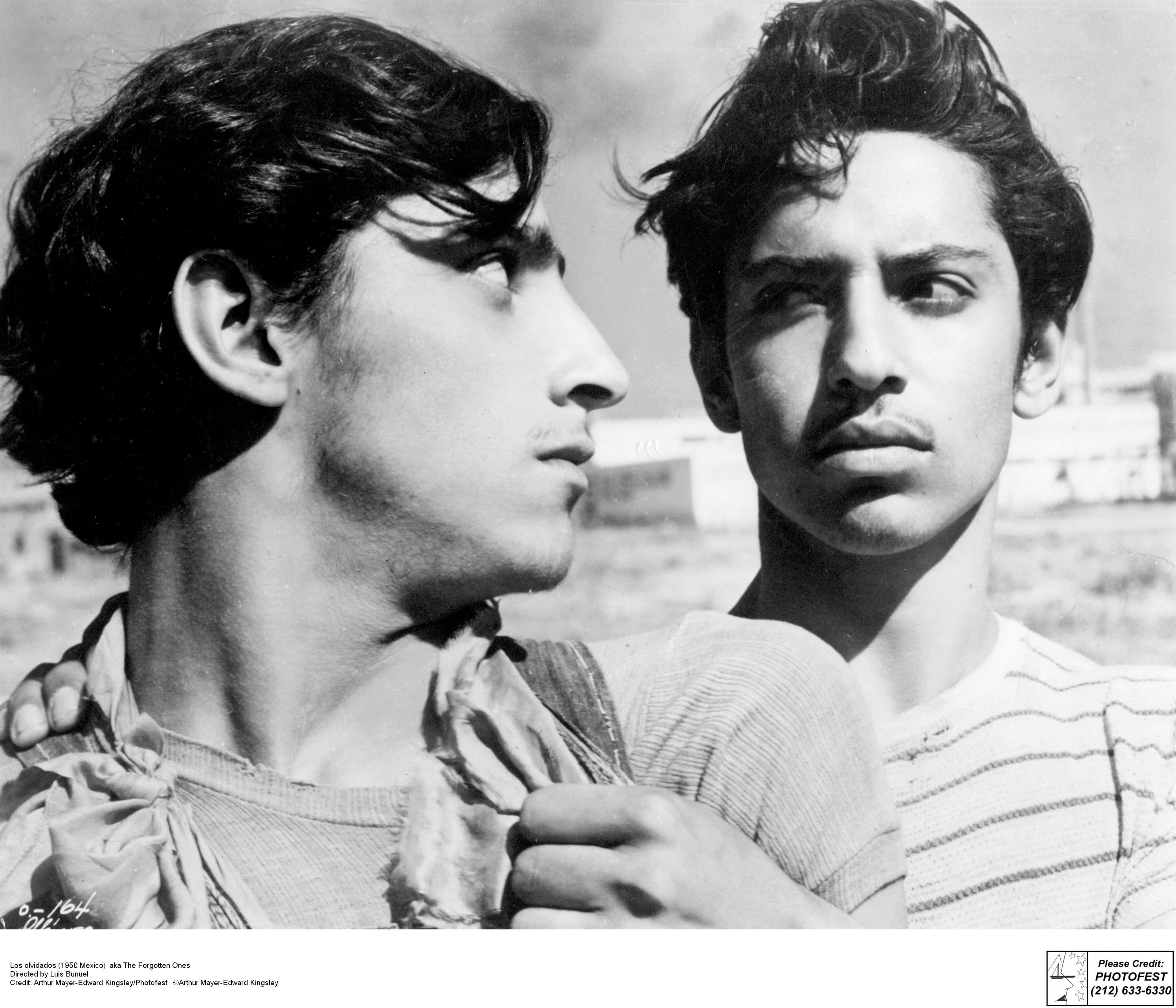

The story centers on the lives of four street kids in Mexico City, four lives deeply entrenched in degradation and abandonment. Pedro steals from his own mother and runs away from home; Meche hides a knife among her ragged clothes; Ojitos waits in vain every day for a father who abandoned him to his fate; and Jaibo lives by his wits, using cunning as a shield to survive in a hostile and ruthless world. These are not merely characters; they are embodiments of a systemic failure, each trapped in a cycle of neglect and violence from which there seems no escape. Jaibo, the older, charismatic delinquent, functions as a corrosive mentor, drawing the impressionable Pedro into his orbit, a cruel reflection of the world's indifference. His presence, a constant threat of both physical harm and moral corruption, underscores the brutal darwinism governing their existence. The children’s aspirations, however fleeting, are invariably crushed by the overwhelming weight of their circumstances, rendering any glimmer of hope not just futile, but almost cruelly ironic.

Four lives stripped of all innocence, devoid of any bourgeois veneer of fatalism. This loss of innocence is not a gentle fading but a brutal amputation, a public vivisection performed for the audience's benefit. Buñuel denies us the comfort of sentimentalism, refusing to romanticize the plight of the poor or suggest that their suffering holds some inherent nobility. Instead, he presents a world where morality is a luxury, where survival necessitates a compromise that destroys the very essence of childhood. This ruthless portrayal distinguishes it sharply from many other social dramas, challenging the viewer to confront a reality that is as ugly as it is undeniable.

A work that in Italy we would have rightly called neorealist, and one which imparts to the viewer the cruel taste of defeat as it unfolds. Indeed, Los Olvidados shares significant DNA with the Italian Neorealist movement that had emerged in the post-war era: its use of non-professional actors, on-location shooting, and a focus on the struggles of the working class and marginalized. Films like Vittorio De Sica's Bicycle Thieves or Roberto Rossellini's Rome, Open City similarly embraced a raw, documentary-like aesthetic to expose social injustices. However, Buñuel's vision here is infinitely more bleak, less concerned with the human spirit's resilience in the face of adversity and more with its inevitable corruption. Where Italian Neorealism, even in its most despairing moments, often clung to a shred of humanist hope or implied the possibility of collective action, Buñuel offers no such redemption. His characters are condemned not just by their environment, but by an almost metaphysical predetermination.

This crucial divergence is perhaps best exemplified by Buñuel's audacious integration of surrealist dream sequences into the otherwise starkly realistic narrative. Pedro's nightmarish vision of his mother, the raw slab of meat, and the slow-motion, grotesque descent of a bull's head, is a jarring, Freudian intrusion that breaks the neorealist mold. It serves not as an escapist fantasy, but as a chilling window into the profound psychological trauma inflicted by poverty and neglect, a primal scream from the subconscious that realism alone could not convey. This stylistic choice, a bold reassertion of his earlier surrealist leanings (Un Chien Andalou, L'Âge d'Or), elevates the film beyond mere social commentary, infusing it with a unique psychological depth that sets it apart from its contemporaries. It is Buñuel reminding us that the horrors of reality are often compounded by the terrors within.

There is no ethical compromise in the narrative; moral judgment is entirely absent. What remains is the raw account that shatters every convention and opens our eyes to a world previously hidden, inaccessible. Buñuel refuses the comfort of easy answers or a cathartic conclusion. The film's ending, abrupt and devastating, leaves the viewer with a profound sense of despair, a testament to the unyielding grip of the socio-economic conditions it portrays. It doesn't offer a path to salvation or a call to action; it simply presents the unvarnished truth, leaving the burden of interpretation and the weight of consequence squarely on the audience's shoulders. This uncompromising stance, a hallmark of Buñuel’s directorial philosophy, ensured that Los Olvidados transcended its national context to become a universal, enduring masterpiece of social cinema, a cinematic punch to the gut that continues to resonate with unsettling power decades after its premiere. It remains a stark reminder that some wounds, once inflicted, refuse to heal.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...