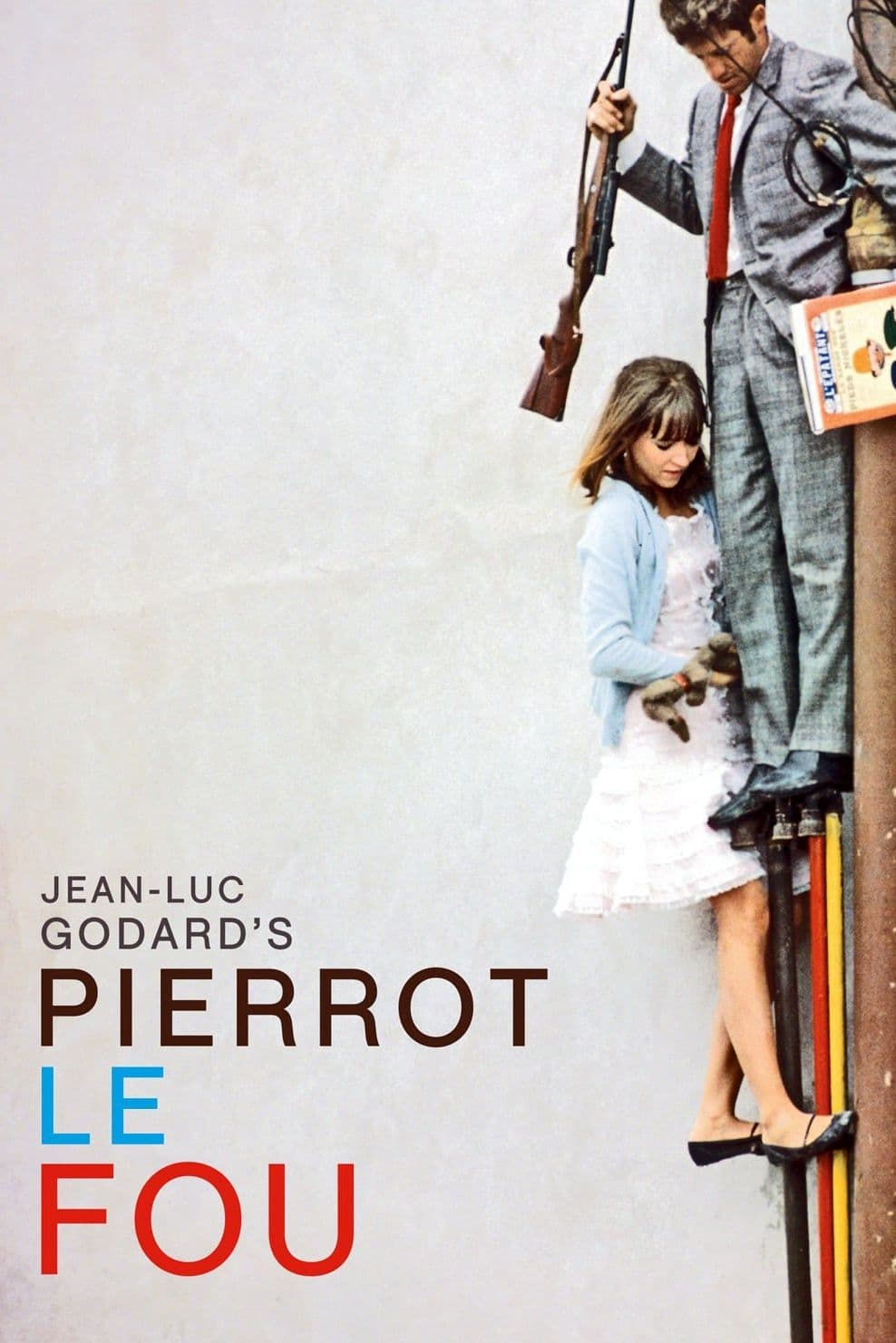

Pierrot le Fou

1965

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Pierrot Le Fou is a story of freedom: from the chains of conformity, from social conventions, from homogenizing routines. Not just any freedom, however, but one that reveals itself as an existential burden, an almost nihilistic yearning in the face of a world perceived as intrinsically false. It is the liberating cry of an era that, while not yet fully the ’68, already carries within it the seeds and fermentation, anticipating that desire for rupture, for aesthetic and ideological rebellion that would later shake the foundations of Western society. Godard, with his unmistakable audacity, does not merely narrate an escape, but paints a fresco of bourgeois disillusionment, of the search for authentic meaning in an existence that seems to have lost it, crushed between alienating advertisements and a mass culture that anesthetizes critical thought.

Godard carves out a metallic character: he loves but doesn't know how to love, he commits crimes but doesn't know how to commit crimes. Ferdinand Griffon, masterfully portrayed by Jean-Paul Belmondo, is a failed intellectual, a television critic who struggles between learned quotations and the primordial urgency of life. His “metallic nature” is not rigidity, but rather a protective shell against the superficiality of his environment, a casing that hides an almost childlike vulnerability. He is an anti-hero par excellence, a Candide of modernism, who attempts to decipher a shattered world with interpretative tools no longer adequate. This contradiction, this friction between his profound nature and his clumsiness in action, is what makes him so humanly complex and, paradoxically, irresistible.

Yet we love him from the first moment he appears on screen and remain utterly fascinated by him. His bewilderment, his thoughtful melancholy, his desperate attempt to define himself through rebellion, resonate with every viewer who has ever felt the weight of societal expectations. The story is that of Ferdinand Griffon, known as Pierrot, a nickname he hates but which inextricably links him to the archetype of the wise fool, the tragic clown who reveals the absurdities of reality.

Tired of ordinary life – a comfortable but empty existence, stifled by meaningless conversations and pastel colors that almost jar with his inner restlessness – he leaves his family and flees with a disturbing Algerian woman named Marianne, portrayed by the enigmatic Anna Karina, muse and then-wife of the director. Leaving a corpse behind, it is not just a fortuitous murder, but a symbolic gesture, a clean break with his previous life, a leap into the void that transforms into an existential odyssey without a clear destination or anchorage. Karina’s Marianne is not a figure of salvation, much less a guide; rather, she is a seductive enigma, an unpredictable and volatile force of nature, whose elusive nature embodies the same unattainable freedom that Ferdinand pursues. Their dynamic is a tango of desire, misunderstanding, and implicit and explicit violence, a relationship that embodies the difficulty – or perhaps the impossibility – of reconciling romantic love with the hunger for absolute autonomy.

It will be a life of escape and excesses, precariously balanced on fragile human laws. They move between the South of France and the French Riviera, in a perpetual road trip that is less a journey towards a destination and more an exploration of the non-place, of suspension, of the limbo between an abandoned existence and a new, still undefined one. This wandering is punctuated by episodes of sudden violence, improvised musical interludes, and surreal dialogues that range from philosophy to politics, from art to cinema itself. The narration shatters, colors explode into an almost pop-art palette – a primary red staining the screen, an intense Mediterranean blue – in stark contrast to the darkness of the themes addressed. Godard rejects traditional narrative coherence, embracing instead discontinuity, temporal jumps, ellipses, almost as if to reflect the fragmentation of the protagonists' psyche and society itself.

A film dense with that detached lyricism, à la Godard, where the viewer is at the center of a complicated hermeneutic process. The director does not merely show; he directly addresses the audience, breaks the "fourth wall" with Brechtian audacity, with direct-to-camera dialogues that strip bare cinematic artifice and remind us that we are watching a film. This self-awareness of the medium is not a mere stylistic flourish, but a programmatic declaration: cinema is not escapism, but a tool for critical inquiry. It is an invitation not to passively accept what is shown, but to actively engage in the construction of meaning. The film thus transforms into a dialectical experience, an intellectual interaction that leaves the final, inexorable judgment to the viewer, which becomes an integral part of the narrated story, and can even change in the viewer's memory: to arrive at the unfinished, or if you prefer, infinite, Work of Art.

Every shot is a stroke of genius, a visual or textual quotation that elevates the film beyond mere narration. There are explicit allusions to Rimbaud, Céline, Faulkner, but also to American cinema classics, in an intertextual orgy that is as much a homage as it is a deconstruction. Raoul Coutard's camera is fluid, almost an eye that breathes and moves with the characters, capturing their intimate essence and sudden transformations. The music, often dissonant or sudden, underscores the sense of precariousness and rupture, contributing to that deliberate disorientation which is an integral part of the viewing pleasure. The famous improvised "Vietnam War" scene in the forest, with its crude and almost grotesque staging, is a striking example of how Godard fused political satire with avant-garde aesthetics, anticipating by decades the debate on the media representation of violence and the increasingly blurred line between reality and fiction. "Pierrot Le Fou" is not just a film, but a manifesto of cinematic modernism, an explosion of ideas that continues to question, provoke, and resonate in the collective consciousness, well beyond its time. It is an intellectual and emotional experience, a bold journey into the anarchy of the human soul and the infinite freedom of art.

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...