The Son

2002

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

The austere, meticulously crafted, and potent cinema of the Dardenne brothers cannot leave anyone indifferent. Theirs is a radical aesthetic and philosophical choice, an almost monastic adherence to a realism that eschews any hint of spectacle, any temptation of narrative embellishment. It is a cinema nourished by the minute, almost entomological observation of the human condition, and by the intrinsic power of the everyday gesture. It is not merely an absence of artifice, but a deliberate subtraction of superfluous elements that aims to isolate the very essence of the drama, making it not only visible but palpable.

Their films are stripped bare of all cinematic adornment – not an absence of technique, but rather a systematic rejection of ostentation, where even their celebrated long takes are never virtuosic, but tools for total immersion, an extension of the gaze that embraces and pursues reality without explanatory cuts; the absence of a soundtrack is not an emptiness, but an invitation to listen attentively to the world, to its noises and its silences laden with meaning; the lyricism of images is replaced by a stark truth that asserts itself; explanatory flashbacks are banished in favor of a narrative that unfolds in the living and uncertain present – all to achieve the total stripping down of the work and its public aesthetic exposure. It is as if every formal element is put to the test, subjected to rigorous scrutiny so that only what is essential, what is structural to the narrative material, can remain.

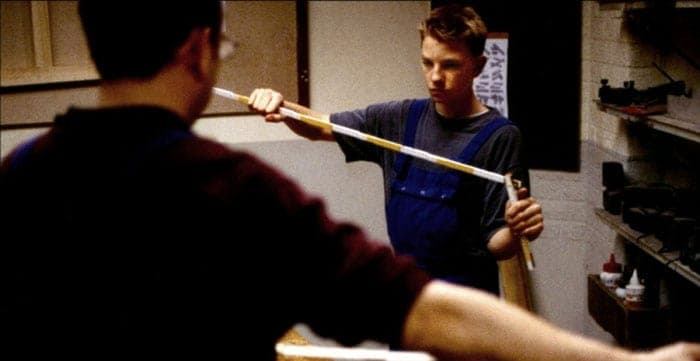

This splendid chapter in their artistic journey is no exception; indeed, it perhaps represents one of its most acute and disturbing manifestations. Their camera rests with its usual discretion on the life of Olivier, a carpenter (the choice of profession is not accidental: a work that shapes, repairs, but also marks and carves, a metaphor for a life trying to reconstruct itself, to give form to pain) who moves with the gravity of one carrying an invisible burden. Olivier, the owner of a carpentry shop, hires a 16-year-old boy from a reformatory and becomes his guardian. In a world that often condemns its fringes without appeal, Olivier offers himself as a bulwark, a mentor, while concealing his own, unconfessable, reasons. This act of apparent benevolence is the first, ambiguous step towards a descent into the abysses of the human soul.

A deeply rooted paternal relationship develops between the two, but from the outset it is imbued with an almost unbearable tension. The Dardenne camera, with its unmistakable handheld agility, becomes a shadow, almost the third wheel in this singular duet, trailing Olivier with a proximity that generates profound discomfort. Yet Olivier proves troubled by the boy, and despite the superficial veneer of their friendship, something casts anguish into the man's soul. It is not merely a reticence or a communication difficulty; it is a visceral unease that manifests in body language, in hesitations, in silences brimming with unspoken words that pervade every interaction. The viewer is placed in a position of constant questioning, almost an investigator of the hidden folds of the soul.

The viewer will only later discover that Olivier is the father of the victim murdered by that boy five years earlier. This revelation, delivered with surgical and almost brutal precision, is not a thriller plot twist, but rather the trigger for one of the most agonizing and morally complex investigations into the theme of forgiveness and revenge ever presented in contemporary cinema. The film thus transforms into a kind of modern Greek tragedy, where destiny and its ineluctable, cruel consequences confront the fragility and strength of human will. There is no easy catharsis, but a close confrontation with the unthinkable: how can one coexist, and even establish a bond, with the embodiment of one's most unspeakable pain? The Dardenne's work does not offer consoling answers, but poses burning questions about the nature of justice – not legal but intimate justice – and about the possibility, or impossibility, of overcoming the primordial impulse for retaliation.

The Dardenne's handheld camera follows the two protagonists, almost spying on them in composed silence, adhering to their movements, their gazes, their hands working the wood. There is no distance between the observer and the observed object; on the contrary, the audience is entangled, almost physically present, in the tension that hovers between Olivier and Francis. This stylistic choice, far from being a mere authorial whim, is the beating heart of their approach. One could almost speak of a tactile cinema, where visual contact translates into an almost epidermal experience, a forced empathy that compels one to confront the suffering of others without filters. The absence of diegetic or extradiegetic music amplifies this effect, allowing the sounds of the world – the scraping of wood, the creak of a door, footsteps on a floor – to punctuate the rhythm of the drama, making every moment of silence a pause laden with foreboding and reflection.

The process of image simplification triggers a subtle mechanism of shared participation in the viewer, what the Greeks called pathos. But it is not a pathos that aims for mere tears or easy identification; it is a pathos that digs deep, that disturbs, that compels uncomfortable introspection. It is the feeling of being witnesses to an internal and external struggle, of a pursuit of forgiveness that is first and foremost a confrontation with oneself, with one's own limits and with one's ability to overcome horror. "The Son" is not just a tale of pain and possible redemption; it is a profound meditation on the ethics of vision, on the responsibility of the gaze. It questions us about the possibility of loving or at least accepting those who have deeply hurt us, pushing the concept of compassion to its extreme. An innovative and touching film, which imprints itself on the soul not for its spectacularity, but for the unwavering force of its human truth, making it a cardinal work not only in the Dardenne filmography, but in the global cinematic landscape, capable of resonating with the power of an ancient tragic chorus in a contemporary context.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...