Hands Over the City

1963

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Rosi's cinema has always been a tool for struggle: exactly like Ken Loach's, it is a means of social denunciation and documented investigation. But while Loach often focuses on individual micro-stories to illuminate systemic dysfunctions, Rosi elevates his investigation to an almost macroeconomic and political dimension, revealing the intricate web of interests underlying current events, transforming every shot into a declaration of civic intent. His is not mere narration, but a filmed inquiry, a counter-reportage that tears away the veil of officialdom to reveal the most uncomfortable truths.

Hands Over the City is perhaps the most committed work in this regard: Rosi denounces the corruption surrounding the city of Naples: rigged contracts, complacent politicians, building speculation, uncontrolled urban sprawl. Naples, in this film, is not merely a picturesque backdrop, but a living protagonist, a canvas onto which the plagues of an unbridled post-war economic boom are projected, the so-called "Sack of Naples" of the 1950s and 60s, an emblem of a construction fever that disfigured the urban landscape in the name of profit. The director does not merely tell a story, but dissects a system, revealing the sinews of power that fuel corruption.

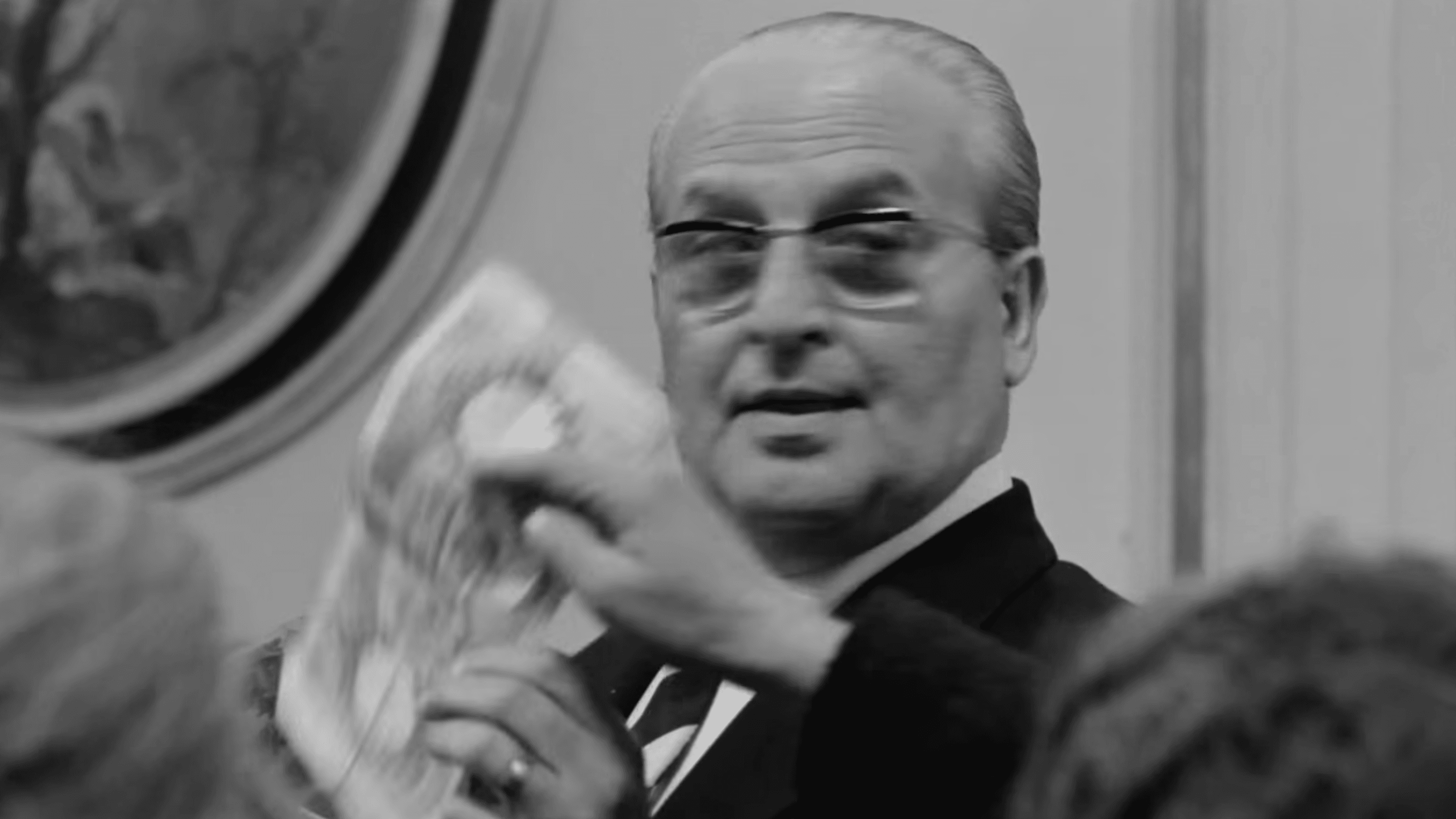

The story centers on Edoardo Nottola (Rod Steiger), a shady character who makes building speculation his primary activity, supported in this by the city's ruling majority. Steiger, with his imposing stage presence and his ability to embody an almost Shakespearean virulence, lends Nottola a complexity that goes beyond simple wickedness: he is a ruthless man, certainly, but also a cunning strategist, a political animal whose ambition knows no bounds, capable of moving with ease through the meshes of bureaucracy and the ambiguities of public morality. His cynicism is not a tic, but his philosophy of life, the inexorable engine of his every action.

An old building in the center of Naples suddenly collapses due to an adjacent construction site owned by Nottola. The tragedy triggers a mechanism of investigation and self-absolution that is the true heart of the film. An investigative committee will determine that the permits were granted regularly – a mockery of justice, a further confirmation of the system's perversion – but Nottola will by then have become an inconvenient figure for the political majority, which will look elsewhere to conduct its sordid affairs, denying him the place on the city council promised in the past. This is the great lesson of the film: there is no honor among thieves, and the system is always ready to devour its own children when they become a burden, or when a sacrificial victim is needed to save face.

Nottola will try in every way to oppose the decision, moving like a wounded predator, desperate in his attempt to reassert his power and influence. His struggle is that of the individual against a Leviathan he himself helped to create, a vicious cycle that embodies the fate of many Rosi characters, condemned to remain trapped in the power dynamics they believe they dominate.

A work of unparalleled documentary rawness, the filming of the city council meetings is truly remarkable, with tight shots of the opposition clamoring while the majority simultaneously raises their hands to show they are "clean hands." This sequence, iconic and almost Brechtian in its allegorical force, is not just a faithful reproduction of parliamentary practice, but a powerfully visual metaphor for democratic farce, where the vote is not an expression of will but a performative gesture, a ritual emptied of meaning, a solid wall of self-interest. Rosi, with his austere direction and black-and-white cinematography that accentuates an almost newsreel-like realism, immerses the viewer in an atmosphere of palpable tension, almost as if it were a real-time journalistic investigation. It is no coincidence that the film won the Golden Lion in Venice in 1963, sparking furious debates and opening a new path in Italian cinema of the era, establishing a genre, that of "civil cinema," which would have illustrious successors in directors like Gillo Pontecorvo with The Battle of Algiers or Elio Petri with Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, while Rosi maintained his unmistakable imprint, almost like a sociologist armed with a camera.

An issue, as can be seen, of sadly pressing relevance. The corruption of Naples is the disease that has consumed Italy from the post-war period to today: corruption, collusion between powerful figures and the business world, political connivance. Rosi's denunciation does not stop at the surface of the scandal, but delves into the depths of a systemic pathology that has infected the country's social and economic fabric, showing how the Italian "economic miracle" harbored, at its core, the germ of rampant speculation and institutionalized illegality. All this is sadly current, and Rosi's film, besides being a wonderful example of protest cinema, remains dramatically vivid and real for our country, a perennial warning that history is not just a succession of events, but a cycle of vices and virtues which, if not recognized and fought, are destined to reappear, to change form but not substance. Rosi's foresight lies in having grasped the endemic nature of such corruption, transforming a local episode into a universal fresco of the eternal struggle between ethics and self-interest.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...