Invasion of the Body Snatchers

1956

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Don Siegel directs a film that pioneers and establishes unsettling paradigms for science fiction: the doppelganger and body snatching patterns. But this is not a mere re-presentation of literary archetypes already explored by E.T.A. Hoffmann or Edgar Allan Poe. Siegel, with his masterful restraint, elevates these concepts to a level of ontological terror, where the threat is not the overt invader, but the insidious, almost invisible loss of self, of one's deepest being. The fear is not of being killed, but of being hollowed out, turned into shells, while perfectly retaining their physical appearance. It is the perfect embodiment of the Freudian "unheimlich": the familiar that becomes strange, disturbing, because what defines us has been irremediably altered.

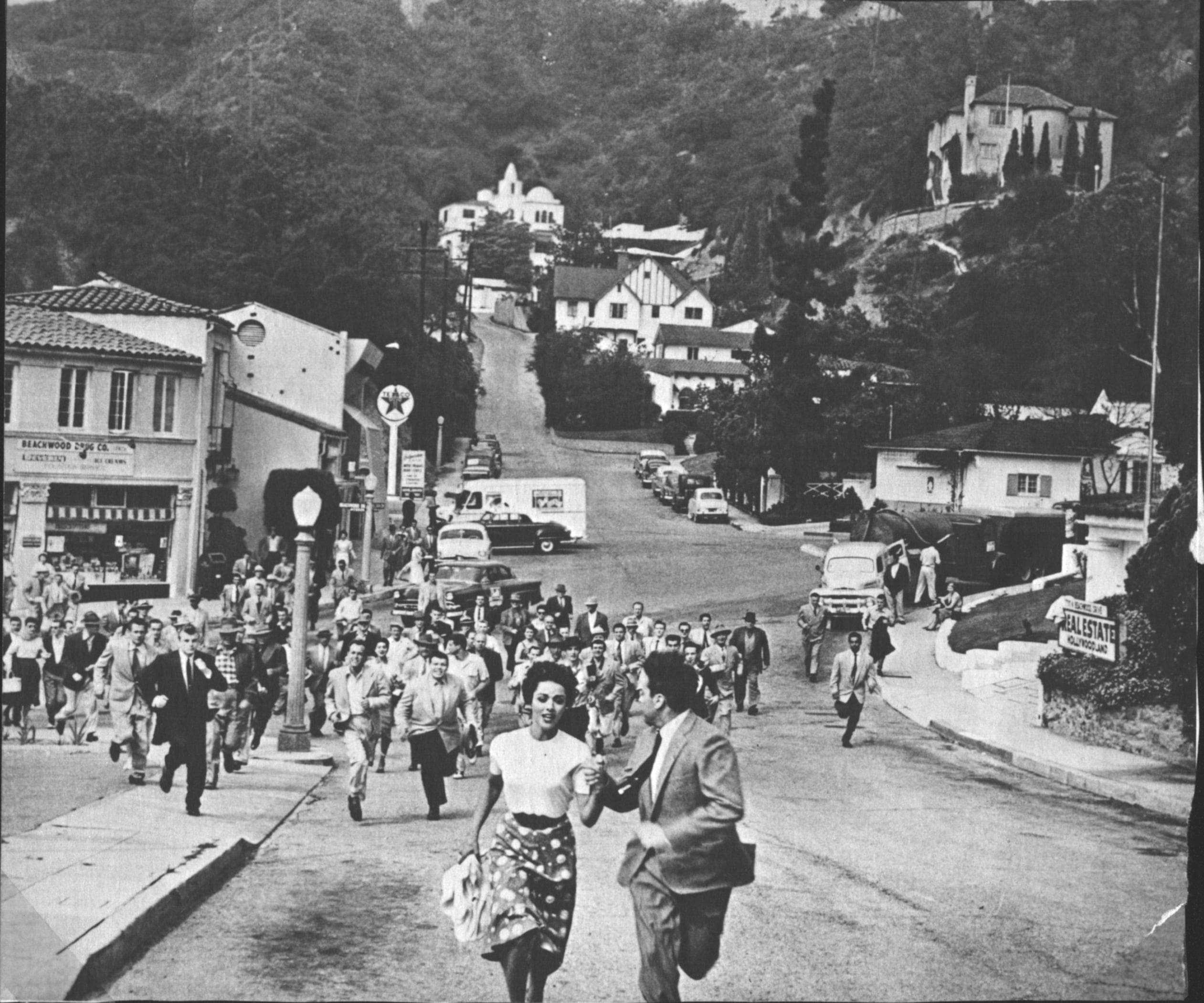

In a sleepy American town, Santa Mira, the inhabitants are gradually replaced by emotionless alien beings, a type of hostile entity that pulls the strings of their host bodies. Their strategy is not military conquest, but biological assimilation: a silent, domestic war, fought in homes, on streets, in suburban gardens. The duplication process, occurring during sleep through gigantic plant pods, is depicted with chilling scientific precision, devoid of fantastic embellishments, making the horror even more tangible and plausible. This mechanism of substitution, which nullifies all individuality and feeling, resonated strongly in 1950s American society, steeped in McCarthyist paranoia and the fear of mass conformity. The Communist threat, portrayed as an ideological contagion that deprived individuals of their freedom of thought, found its most vivid and ambiguous cinematic allegory in Siegel's film, allowing the viewer to interpret the "pod people" as the embodiment of the Red Scare or, conversely, as a critique of the suffocating conformity of a society that imposed the suppression of emotions and differences.

An exciting journey into the human psyche and the concept of identity. But also an exhausting confrontation between self and the other. Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy), the protagonist, finds himself fighting not against recognizable monsters, but against the familiar faces of his neighbors, friends, and even the woman he loves, all transformed into replicants devoid of human warmth. His solitary odyssey through an apparently normal city, now devoid of authentic humanity, is a Kafkaesque nightmare where reality itself warps. The tension derives not from jump scares, but from the growing anguish of no longer being able to trust anyone, of no longer distinguishing the original from the perfect copy. The film explores the fragility of human bonds and existential solitude in the face of a threat not fought with weapons, but with the desperate safeguarding of one's soul and one's capacity for emotion. The "sleep" from which one awakens as an alien, devoid of anxieties and pains, is a disturbing metaphor for the renunciation of one's humanity in exchange for an unnatural and apathetically imposed peace.

A work whose semantic richness has been plundered throughout cinematic history by dozens of filmmakers enamored with its unique atmosphere, its grim unease, the sense of silent horror it conceals behind every frame. From John Carpenter's claustrophobic masterpiece, The Thing (which shares the paranoia of replacement), to the subsequent, albeit meritorious, reinterpretations by Philip Kaufman in 1978 and by Abel Ferrara in 1993, the echo of Siegel's film is omnipresent. Kaufman, in particular, reinterpreted the allegory, shifting it from the Cold War to post-Watergate paranoia, with an emphasis on the loss of trust in institutions, but he did so with a budget and means that the original could only dream of, and which nevertheless did not tarnish its purity. Siegel's ability to generate such profound terror with a modest budget, utilizing black and white to accentuate shadows and alienation, and an essential direction that favored close-ups and fluid camera movements to capture Miles' growing desperation, is a masterclass in filmmaking. His "silent horror" manifests in the subtle, yet devastating, emotional disconnect of the replicants, in their empty stares, in their forced smiles that betray the absence of a soul.

Needless to say, no one has managed to reproduce its magical blend of horror, psychological thriller, and science fiction. Invasion of the Body Snatchers transcends the genre, establishing itself as a treatise on the nature of identity and the threat of dehumanization. Its power resides not in special effects – almost non-existent – but in its fundamental ambiguity, in its being a palimpsest onto which the most recondite fears of every era can be projected. The ongoing debate over its political interpretation (anti-communist or anti-McCarthyist?) has for years been a source of critical fascination, but the truth is that the film operates on a more universal plane: that of the fear of losing what makes us unique and human, whether at the hands of an external enemy or through an internal pressure for conformity. The ending, imposed by the production and more optimistic than Siegel's original (which depicted Bennell desperately screaming to an indifferent world), fails to undermine the desperate power of its message: resistance is solitary, the threat is omnipresent, and salvation is never guaranteed. A timeless classic, whose unsettling relevance persists in every era in which the concept of individuality and freedom of thought seem threatened.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...