Winter Light

1963

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Winter Light is a more austere, colder work, but perhaps even more radical than other gems of Ingmar Bergman's cinema. It is the central panel of the so-called “Trilogy of the Silent God,” nestled between the schizophrenic delirium of Through a Glass Darkly and the total absence of God in The Silence, and is undoubtedly the purest and most formally rigorous chapter. If a film like Symphony of Autumn is an emotional explosion, a supernova of resentment and filial love, Winter Light is a spiritual implosion, the collapse of a star of faith into a black hole of doubt. It is one of the most difficult and desolate films ever made, but its intellectual honesty is so disarming and its artistry so distilled that it is essential to the history of cinema.

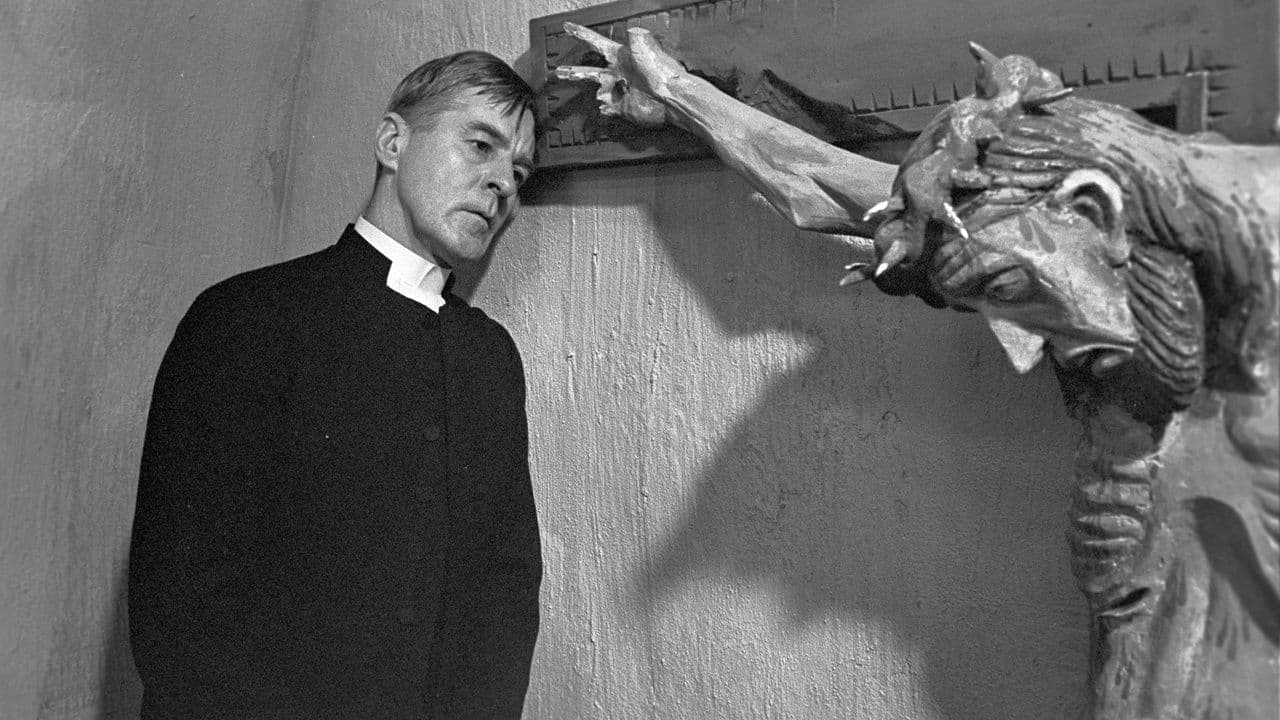

The film is a requiem for faith in the modern age, an age of nuclear anxiety and growing secularization. It recounts a few gray hours in the life of Tomas Ericsson, a pastor in a small rural Swedish community who, after the death of his wife, has also lost the ability to believe in a God who remains stubbornly, deafeningly silent. The photography by Sven Nykvist, Bergman's key collaborator, is icy, almost documentary. At the director's request, Nykvist studied the quality of natural light inside country churches during the winter, and the result is a work that seems illuminated by a pale, sickly sun. The light offers neither warmth nor revelation; it merely makes the cold visible, both outside and inside the soul. The compositions, in their stark simplicity, are almost reminiscent of Morandi's paintings, with their bare interiors and solitary figures immersed in a melancholy-laden stillness. It is a film made up of faces, silences, and unanswered questions. Tomas' crisis is not only religious, it is existential: how can you comfort others when you have no comfort for yourself? How can you talk about love, divine or human, when you are incapable of receiving it?

Winter Light is part of a pan-European artistic dialogue. Bergman was not alone. In those same years, other prophets of incommunicability were mapping the spiritual desert of the post-war period. The most immediate parallel is with Michelangelo Antonioni, whose characters wander through urban or industrial landscapes that mirror their inner emptiness. But there is a crucial difference: Antonioni's incommunicability is a disease of modernity, a social and emotional alienation. Bergman's is a theological alienation. His characters cannot communicate with each other because they have lost their primary interlocutor: God. It is from this cosmic silence that their inability to love and be loved descends. Another great practitioner of distant dialogue is Andrei Tarkovsky, who, like Bergman, explored faith and doubt. But while Tarkovsky's cinema is an exhausting struggle toward a glimmer of grace, a search for transcendence, Bergman's cinema at this stage is the chronicle of a defeat, the study of a faith that is dying. Later directors such as Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch would inherit this sensibility, telling stories of characters adrift in a world emptied of grand narratives, but they would often do so with a filter of irony or coolness that was entirely foreign to Bergman's almost masochistic sincerity.

At the heart of the film is the collapse of the Word, the decay of the Logos. Tomas is a pastor, a man whose job is to dispense the divine Word, the word that should bring comfort, meaning, and salvation. But his Logos has become empty. He recites sermons written by others, his prayers are mechanical formulas. Communication, in this frozen world, becomes a disease. When Jonas, a fisherman tormented by anxiety about the atomic bomb, turns to him for help, Tomas has nothing to offer but his own contagious despair. Instead of saving him, he “infects” him with his doubt, hastening his suicide. Similarly, human love, represented by the teacher Märta, is expressed through a long and heartbreaking letter, a desperate attempt at communication that is rejected by Tomas with chilling cruelty. Words do not build bridges, but dig abysses. They do not heal, but reveal and transmit pain.

This is why the silences in this film are so eloquent. They are not mere pauses in the dialogue. They are the main character of the film. They are the Silence of God made audible. It is an active silence, charged with tension, a void that the characters clumsily attempt to fill with their inadequate words, only succeeding in making it even more evident. Bergman's long close-ups of his actors' faces are often shots of people listening to this silence, waiting for an answer that will never come. The silence after the news of Jonas' suicide, the silence in the sacristy, the silence of the empty church: these are not the absence of sound, but the palpable presence of an absence, that of God. The ending is one of the most ambiguous and powerful conclusions in the history of cinema. After losing a parishioner and brutally rejecting the only person who loves him, Tomas decides to celebrate the afternoon service anyway. The organist advises him against it: there is no one in the church except Märta. But Tomas insists. He walks toward the altar to begin the service in an empty church. What does this gesture mean? Is it an act of renewed, more humble faith, celebrated not for an absent God but for the only human being left to listen? Is it an act of desperate, absurd obstinacy, a ritual emptied of all meaning, a habit that continues out of inertia? Or is it the beginning of something else? Bergman gives us no answer. He leaves us alone in that empty church to contemplate the doubt. And in this radical honesty, in this rejection of any easy consolation, lies the immortal greatness of the film.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...