Cinema Paradiso

1988

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

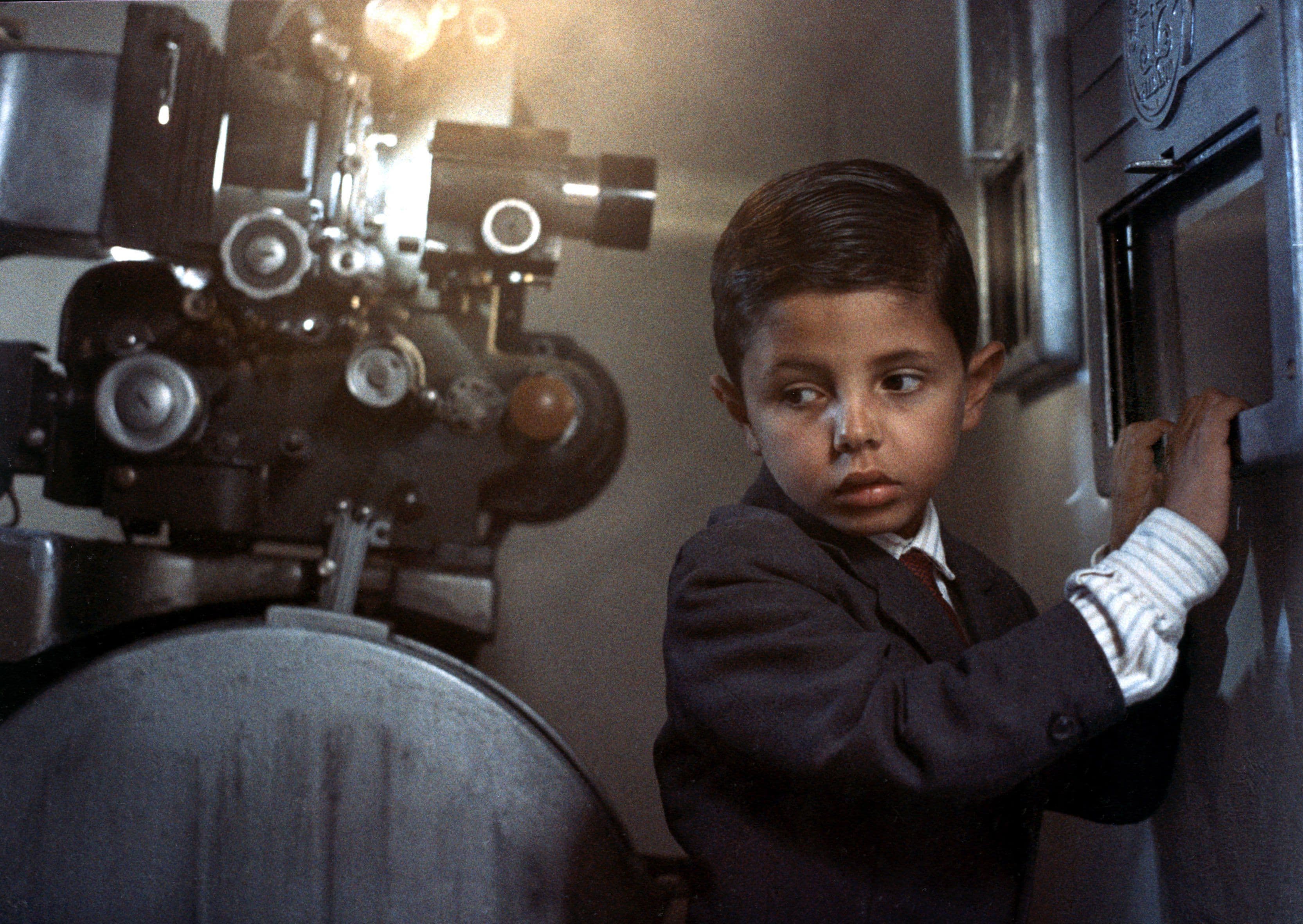

Giuseppe Tornatore grappling with his own memories pays homage to a humble projectionist who initiated him into the mysteries of cinema, making him fall in love with those stories projected from afar, in a smoky hall, amidst coughs and passionate kisses. This initial, striking image paints an intimate epic, a profound reflection on the individual's formation through art. The director does not merely evoke the past, but intends to crystallize an era, a universal feeling: that of discovery, of the primordial enchantment stemming from the encounter with the Seventh Art. It is the tale of an initiation not only artistic but also existential, filtered through the bittersweet veil of nostalgia, a Proustian "madeleine" that smells of celluloid and childhood memories.

And he does so with such candor, poeticism, and crystalline language that it is impossible to remain indifferent to the final result of his efforts. Tornatore's mastery manifests in a lyrical, almost symphonic direction, where every frame is chiseled with the precision of a chisel and the delicacy of a brush. Ennio Morricone's soundtrack contributes indissolubly to further elevating this visual score. His melodies, evocative and poignant, are not mere accompaniment, but a true narrative voice, capable of amplifying the pathos of the scenes and imprinting the images on the viewer's memory with the force of an anthem to lost beauty. It is a work in which emotion is never forced, but arises naturally from a narrative that proceeds by accumulating small, significant details.

One might call it a meta-cinematic operation: cinema talking about cinema, as Truffaut had already done from a different angle. Certainly, the parallel with Truffaut's La Nuit américaine (translated into Italian as Effetto Notte) is inevitable and illuminating. But if the French director's masterpiece investigated the secret mechanics of cinematic creation, the behind-the-scenes, with all its idiosyncrasies and fleeting magic, Tornatore shifts the focus. He does not delve into dusty sets or the challenges of a film crew, but rather into the sacred darkness of the hall, into the collective ritual of viewing.

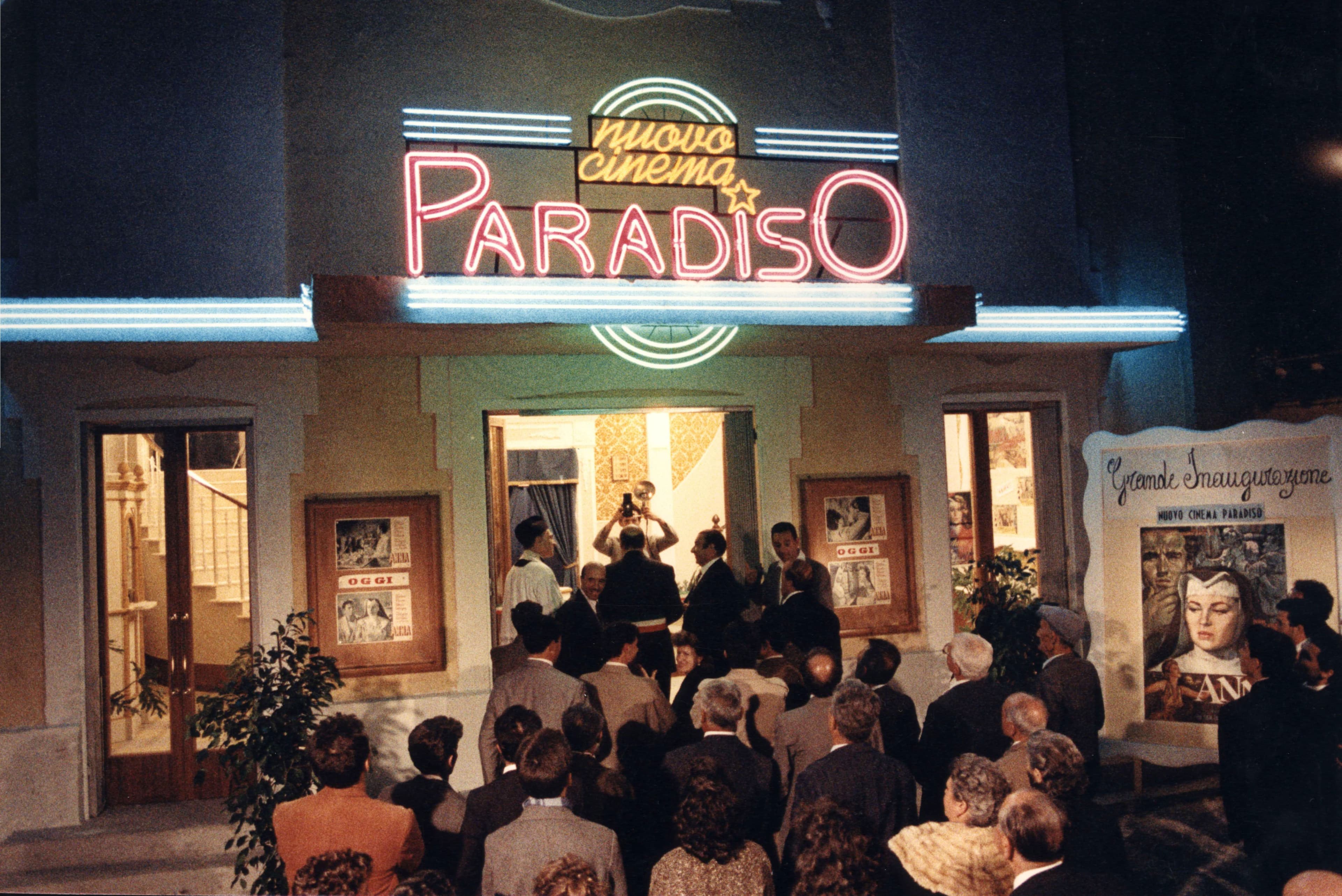

If the French director's perspective was indeed that of cinema in the making, Tornatore speaks of cinema as experienced by the audience. Nuovo Cinema Paradiso is an ode to the cathartic and democratic experience of viewing, to the screen's ability to serve as a mirror and a window onto the world for an audience hungry for dreams, especially in post-war Italy, where cinema was often the only escape from a reality still marked by privations. It is the story of a place that was much more than just a building: a secular temple, an emotional agora where laughter and tears mingled, where love was born furtively and life was reflected, filtered by the light of a film reel. The figure of the projectionist, Alfredo, thus becomes not only a technician, but a true guardian of dreams, a demiurge who, with his touch, brings fantastic universes to life, not without having to contend with ecclesiastical censorship, symbolized by the sharp bell of the parish priest that tore through the illusion, mutilating the boldest kisses and embraces.

Add the masterful performance by an accomplished actor like Philippe Noiret to get an idea of the greatness of this film. Philippe Noiret's weathered face and good-natured wisdom imbue Alfredo with a rare and inimitable depth. Noiret does not merely act: he embodies the paternal and mentor figure, an anchor of stability and affection in a rapidly changing world. His chemistry with Salvatore Cascio, the child who plays Totò picciriddu, is palpable, imbued with that gruff tenderness that makes their bond credible and moving, one of the most successful cinematic duos of master and pupil. It is through Alfredo's eyes that we learn to decipher the love for cinema, his melancholy for a changing world, and his strenuous, almost stoic, faith in the future of his young protégé.

The story is that of a Roman director who returns to his native "wild village" in Sicily for the death of an elderly projectionist who had initiated him into the mysteries of the Seventh Art. Salvatore's return, now an established director, to his ancestral Sicily is not merely a dutiful act, but an introspective journey into the labyrinth of memory. The narrative unfolds on multiple temporal planes, with flashbacks cascading, revealing Totò's lively and curious childhood, his almost filial relationship with Alfredo, but also his first, lacerating love for Elena, an adolescent passion that shapes the protagonist's soul and partly determines his subsequent life choices.

It will be an opportunity to revisit through memory places, lives, past emotions that resurface within him with the power of a new and incontrovertible language. Every frame oozes with this mnemonic re-emergence: the clinking of coins in the projection booth, the dense smoke that filled the hall, the laughter and comments of the audience, the cut sequences of kisses that Alfredo clandestinely accumulated – all pieces of a mosaic that reassembles in the protagonist's heart. It is a journey that, while imbued with nostalgia, never succumbs to easy sentimentalism, but rather confronts the inevitable transformations that time imposes. The destruction of the old cinema, its implosion into a pile of rubble that gives way to progress, is a powerful symbol of the end of an era, but also of the necessary, albeit painful, evolution of an art in new forms.

He will relive the relationship with Alfredo, the projectionist of the only cinema in the small Sicilian town, his wisdom, his irony, his flashes of humor that illuminate memories with a warm melancholic light. A symbiotic, almost platonic relationship, that between master and pupil, which transcends mere technical instruction to embrace sentimental and moral education. Alfredo is Totò's Virgil in the purgatory of passions and the paradise of images.

As a child, he frequented Alfredo's projection booth, unveiling its obscure mysteries, until, as a young man, he left to seek his fortune outside Sicily. Totò's departure for Rome, urged precisely by the mentor who exhorts him not to look back, marks the transition from innocence to maturity, from protection to the solitude of success.

Alfredo's farewell speech is a wonderful synthesis of affection and wisdom: "Don't come back anymore, never think about us, don't turn around, don't write. Don't let nostalgia screw you over, forget us all. If you can't resist and come back, don't come to see me, I won't let you into my house. Did you understand? Whatever you do, love it, as you loved the paradise booth when you were a little boy." These words, burned into Totò's memory (and the viewer's), are not a mere farewell, but a viaticum, a categorical imperative to embrace the future without regrets. Alfredo, though aware of his role as a paternal figure, recognizes the necessity for Totò to fly away, to break the chains of tradition and geography to fulfill his own destiny. It is a universal life lesson: the courage to leave the nest, to face the unknown, but always with an intact passion for what one undertakes. And precisely this last recommendation – "Whatever you do, love it, as you loved the paradise booth when you were a little boy" – reveals itself to be the true spiritual testament, the key to understanding the final gift Alfredo reserves for his protégé: that clandestine reel, a compilation of all the censored kisses, which unspools on the screen at the end of the film. That final montage, poignant and cathartic, is not only a tribute to cinema and its ability to preserve the most intense moments of human emotion, but is the culmination of Totò's journey, the reconciliation with his own past, and the rediscovery of a pure and unconditional love, exactly like that for the "paradise booth." It is the celebration of memory not as a prison, but as an inexhaustible source of inspiration and life, a legacy that earned the film a well-deserved Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film and a place of honor in the pantheon of world cinema.

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...