Onibaba

1964

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A sea of towering grass is swayed by the wind, which seems to cling to the tender stalks, playfully creating swirling ripples. Everywhere the eye reaches, there is Susuki, seduced by the wind, the Japanese pampas grass that conceals things and men like a huge dormant Demon. The opening shot of Onibaba is of a chilling beauty. Kaneto Shindo, a refined aesthetician, thus chooses the opening of his film, obliquely introducing the narrative and allowing Nature and its shadowy artifices to speak at length, in a black and white that unfurls this bucolic enchantment with studied charm, leaving the viewer at the mercy of the wind's somber howl and a guttural, cacophonous music. This choice is not merely stylistic; the black and white, in particular, accentuates contrasts, making shadows denser and light rawer, almost as if to strip bare the very essence of a primordial world where nature is both refuge and an ineluctable threat. The Susuki, with its majestic and deceptive beauty, stands as a true character, a verdant labyrinth that conceals secrets, nightmares, and the raw reality of survival. It is not just a backdrop, but a living barrier, a permeable boundary between the human and the bestial, the visible and the invisible, an almost sentient entity that observes and swallows. Its omnipresence and incessant movement, evoked by the wind, create a sense of claustrophobia and isolation, transforming the landscape into an open-air prison. The sound, with its almost animalistic howl and those soul-scraping dissonances, completes the picture of a sensory immersion in desolation, foreshadowing the brutality of the coming events and anchoring the narrative to an almost mythological dimension, where survival becomes an ancestral ritual.

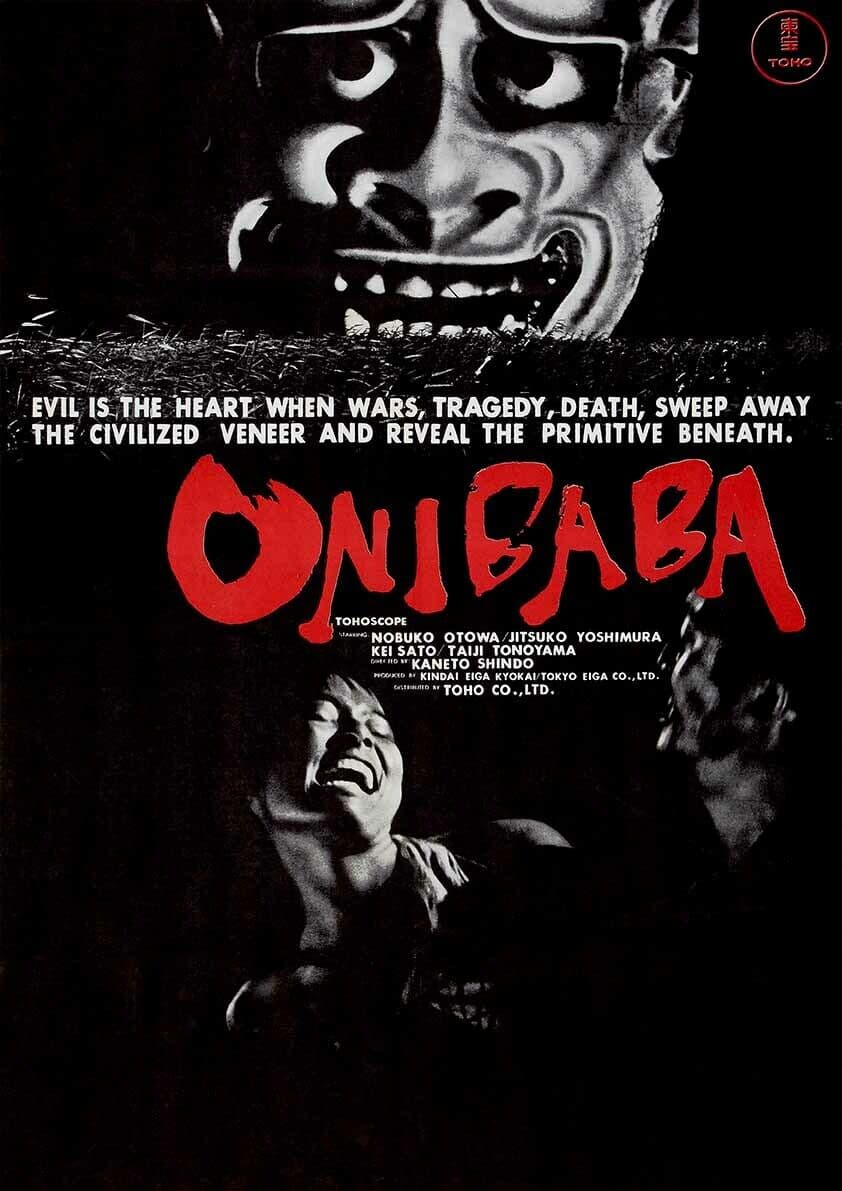

Two wounded, fleeing samurai seek refuge in this teeming green barrier, attempting to escape enemies on horseback. Once they believe themselves safe, they collapse, exhausted, onto the ground. And it is precisely in that instant of ephemeral safety that they are struck by an invisible spear that kills them instantly. From the thick of the grass appear two female figures: they are the thieving and murderous protagonists of the story. Two women from whom war has taken their men, who struggle to survive by killing soldiers and selling their swords and armor for a handful of millet. The elder is the mother of the young woman's husband; both live in a hut hidden by the tall Susuki stalks, a life of poverty and sacrifice awaiting the son's return. We are in the 16th century, in the midst of the Onin War, which pitted the Kanrei, the feudal lords, against each other in a fierce and merciless struggle. The survival of the civilian population during this period is truly put to the test: crops are destroyed, men are all engaged in conflict, and women, children, and the elderly die of hunger in the countryside. The two women's routine is disrupted by the arrival of a neighbor, a battle companion of their son Kichi, who returns home after atrocious wartime events. The man announces that Kichi died in the war and seduces his wife in an intense courtship that culminates in unbridled passion between the two. Kichi's mother opposes this relationship in every way, selfishly fearing being left alone and no longer being able to kill or steal to survive. So she devises a diabolical plan: she steals a demonic mask from a passing samurai, killing him, and uses this disguise to scare her daughter-in-law and deter her from the pleasures of the flesh. But the power concealed by the Mask will turn against the woman in a terrible final coup de théâtre. But beyond the mere succession of events, Shindo weaves a complex allegory on human nature and the corrupting power of despair. The initial killing of the samurai, carried out with an "invisible spear," is not a mere narrative device; it is a premonition, a metaphor for the arbitrary violence that governs that world and seeps into the lives of the weak, turning them into tormentors in turn. The Susuki grass, here, is no longer just a hiding place, but a silent accomplice in a self-perpetuating cycle of death. The mother figure, obsessive and reactionary, embodies an atavistic fear of loneliness and loss of control, a visceral dependence on her daughter-in-law that transcends filial affection to become pure manipulation. Her opposition to the young woman's sexuality and desire is not merely selfishness; it is the rejection of life trying to break through in a context of death, it is the fear that pleasure might distract from the struggle for survival, weakening the forced alliance between the two women. Hachi's arrival upsets not only physical balances but, above all, psychological and emotional ones, triggering a chain reaction that leads to the emergence of primal instincts. The demonic Mask, taken from a samurai already deformed in his humanity by war and the stench of death, transcends its role as a mere disguise. It becomes a powerful symbol: an embodiment of jealousy, resentment, perversion, but also of the weight of past actions and karma. It recalls Noh theater masks, not only for its unsettling aesthetic but for its ability to transform the actor into an otherworldly entity, to reveal the character's spiritual or demonic essence. Here, however, the mask is not a temporary accessory; it merges with the skin, becoming one with identity, revealing the latent bestiality and inner corruption that war has instilled in souls. The horror of Onibaba is not supernatural, but profoundly human, rooted in misery and dehumanization.

Shindo's interest is not in war, but in those who suffer it. His vigilant eye is focused on the weakest and the myriad artifices they employ to survive. In a famous statement, the director indeed said: "My eye, or rather the camera's eye, is aimed at observing the world from the lowest level of society. And if you have to look at society through the eyes of those at its lowest stratum, you cannot escape the fact that you must experience and perceive everything with a sense of political struggle between classes." And it is precisely this immense battle for survival that is the focal point of his works. We recall The Naked Island and the harshness of its protagonists' lives as they strive to cultivate a plot of land, wresting it from the fury of Nature. In Onibaba too, this tremendous tension towards life among the humblest is the cord that makes the narrative vibrate, and is ultimately its atrocious enchantment. This perspective, which Shindo defined as "the camera's eye" aimed "from the lowest level of society," is not a stylistic flourish but the pulsating heart of his poetics, a political and humanitarian manifesto that resonates deeply in post-war Japan, still marked by the scars of a devastating conflict. If in The Naked Island the struggle was primarily against adverse Nature and physical toil, in Onibaba to this is added moral and spiritual putrefaction, the descent into bestiality when civilization gives way to the instinct of self-preservation. The film, in fact, though set in the 16th century, is a timeless reflection on war and its consequences for the human soul, a desperate cry against the dehumanization it entails. The horror of Onibaba is not generated by external ghosts, but by the internal demons that despair and deprivation unleash. The mask is not an added fantastical element; it is the face that hunger and fear forge, an almost expressionistic symbol of inner torment. Shindo proves himself a master in distilling the essence of human cruelty, revealing how war not only destroys bodies and infrastructure but corrodes the most intimate relationships and transforms individuals into predators. His lucid and disenchanted gaze dwells on the animality that emerges when all social superstructures collapse, when morality becomes an inaccessible luxury. In this, Onibaba ranks among the great existentialist films of Japanese cinema, capable of exploring the limits of human dignity in extreme circumstances, leaving the viewer to confront their own capacity for survival and compromise, far beyond the confines of a simple historical narrative. It is a work that, with its powerful aesthetic and raw message, continues to question our very nature, our capacity to fall and to rise again, or to sink into an abyss of barbarity when the veil of civilization is torn asunder.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...