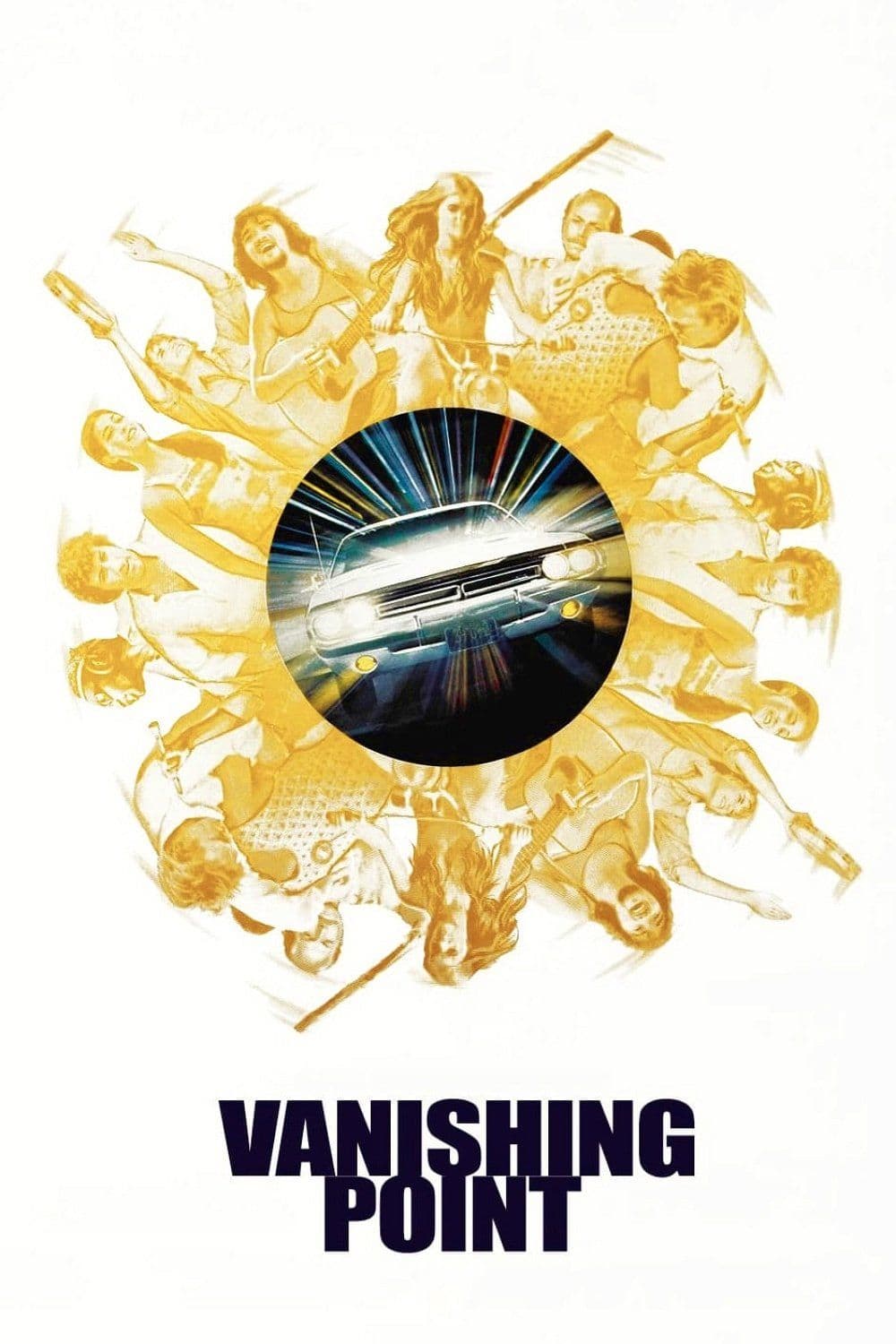

Vanishing Point

1971

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Kowalski is a lightning bolt in dark glasses and sideburns, tearing across the States in a Dodge Challenger at breakneck speed. An icon on wheels, white as a mad shard in the scorching desert, a tangible emblem of a longed-for, almost desperate, freedom.

For a bet, he must reach San Francisco in under 15 hours, starting from Colorado, where he fueled up on gas and amphetamines. But beyond the bet itself, what drives Kowalski is something deeper, an existential urgency that pushes him to the margins of every convention. An ex-cop, ex-race car driver, ex-soldier in Vietnam, his is not an ideological rebellion but a cathartic escape from a world that has disillusioned him, a search for oblivion or one last, glorious adrenaline rush before the end. His Dodge is not just a mode of transport, but an extension of his will, a bullet fired against the established order and, perhaps, against himself.

In this short span of time, Kowalski, a shadow-man from whose figure only fleeting traces of a tormented past emerge, will transform into a role model for some, and a serious threat to national security for others. His passage is a roar that breaks the silence of American highways, a signal that authorities, in a climate of growing post-Vietnam paranoia, cannot afford to ignore. His drive becomes a media epic, amplified and distorted by radio voices that transform him into a living symbol, a modern Sisyphus pushing his rock at 200 miles an hour towards an indefinite horizon.

A great little B-movie that became a cornerstone of the Exploitation genre, revered by generations of filmmakers (Tarantino would pay homage to it in "Grindhouse – Death Proof" using the same car model). But it would be reductive to confine it solely to the "exploitation" label, even though its independent roots and focus on raw action are part of it. Punto Zero (original title Vanishing Point) is, in reality, an existential parable imbued with beat melancholia, a film that, beneath the apparent simplicity of its plot, conceals a profound meditation on freedom, destiny, and identity in a torn America. Richard C. Sarafian's direction, tense and essential, accentuates the sense of urgency and solitude, transforming the vast desert landscapes into a desolate stage for an inner drama.

The film reintroduces the absolute myth of freedom from every constraint and every hindrance, a kind of Easy Rider on four wheels. But the analogies quickly exhaust themselves, revealing substantial differences. If the protagonists of Easy Rider sought a community, an alternative, a haven in the hippie utopia, Kowalski is not interested in being a hero, much less a model for the beat counterculture; Kowalski is only interested in arriving in San Francisco on time and getting properly drunk. His is a solipsistic rebellion, not communal; an act of defiance not towards an ideal, but against every vestige of hope. His "San Francisco" is not an Eden, but a limit, a vanishing point beyond which there is nothing left to achieve.

A man who, despite himself, becomes an icon of rebellion against all institutional constraints and every rule that restricts freedom of expression. This involuntary mythologization is skillfully orchestrated by the figure of the blind DJ Super Soul, who, from his radio booth, acts as an oracle and chronicler of Kowalski's deeds, amplifying his legend and transforming him into a modern messiah for the restless souls scattered across the country. Super Soul is the voice of the counterculture, the prophet of the radio desert who, with his biblical parables and blues-rock music, elevates Kowalski's flight to an epic gesture, almost a pagan sacrifice on the altar of individual freedom. It is through his commentaries that the film acquires an almost mystical dimension, elevating a simple car chase to a metaphor for the human condition, for rebellion against an ineluctable fate.

The use of music, a soundtrack skillfully interwoven with country, blues, and rock tracks, is not a mere accompaniment, but a fundamental narrative element that marks the rhythm of the flight and amplifies its emotional and political resonance. The songs become Kowalski's inner voice and the soundtrack of an era of profound disillusionment.

A revolutionary work against all forms of homogenization, Vanishing Point stands alongside other gems of 1970s American cinema like Two-Lane Blacktop and Duel, distinguishing itself with its unmistakable vein of heroic despair. It is not just a road movie, but an allegory of the end of an era, of the disintegration of the American dream, and of the last, mad dash towards a vanishing horizon, just like the "vanishing point" of the title, a mirage on the road leading to final annihilation. Its raw and uncompromising ending is the summation of this philosophy, an act of self-determination that elevates Kowalski from a mere fugitive to a martyr of freedom, a searing warning etched forever into the collective imagination.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...