The Killing

1956

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Before becoming the monolith of 20th-century cinema, the architect of future worlds and past nightmares, Stanley Kubrick was a young, hungry director who, with The Killing (1956), created not only a tense, flawless noir film, but a veritable manifesto of method. Beneath the surface of a high-tension B-movie, his entire poetics are already stirring, his obsession with control, chaos, and perfect systems destined to implode due to the most unpredictable and flawed element of all: the human being. Watching this film today means observing the DNA of a fully formed genius, recognizing the filigree of his art destined to change the history of cinema. His direction is already clinical, almost divine, a camera that does not empathize with its characters but observes them like insects in a terrarium, studying their movements with the cold curiosity of a scientist witnessing an experiment doomed to failure.

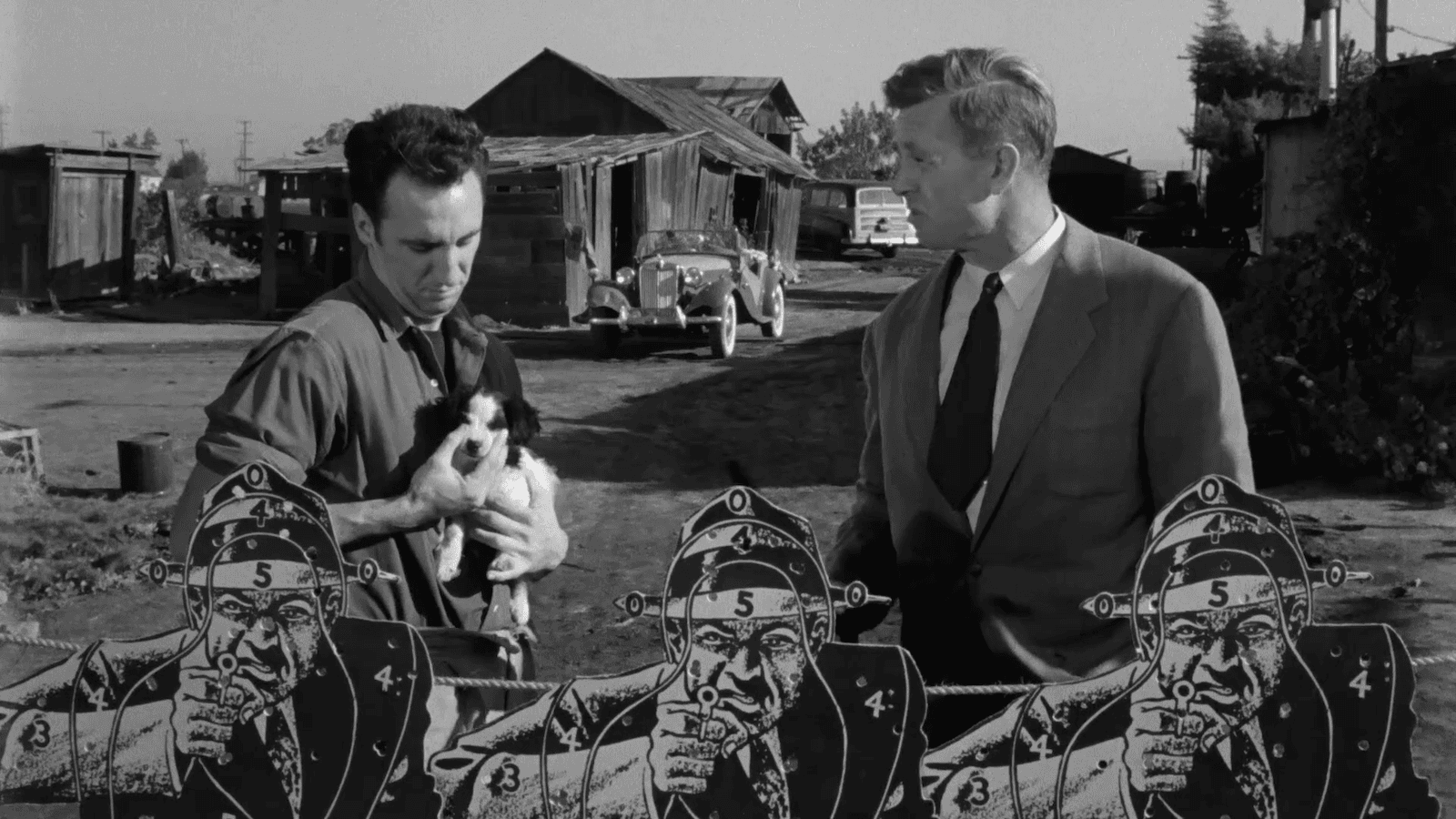

The film chronicles the planning and execution of a racetrack robbery, a two-million-dollar heist masterminded by the brilliant and laconic Johnny Clay (a magnificent Sterling Hayden). The narrative structure Kubrick adopts is revolutionary for its time and for American cinema. He abandons linearity to construct a temporal puzzle that jumps back and forth, showing us the same moments from different perspectives, following each member of the gang in their specific task. This fragmented editing is not a stylistic quirk; it is a philosophical choice. It transforms the robbery into a perfect mechanism, a Swiss watch where every cog must click into place at exactly the right moment. This obsession with process and system would be a constant feature of his cinema: from the HAL 9000 computer that goes haywire in 2001: A Space Odyssey to the dehumanizing routine of military training in Full Metal Jacket. The parallels with crime cinema before and after this film are illuminating. If the benchmark for the genre was John Huston's The Asphalt Jungle, a masterpiece that explored the human and tragic side of its criminals, Kubrick moves to a more abstract and formal plane. He is less interested in the souls of his characters than in the mechanics of their failure. In this, The Killing becomes the prototype, the Rosetta Stone of the modern heist movie. Its archetypes—the charismatic leader, the insider, the muscle, the sniper, the weak link with the unfaithful wife—will be plundered for decades. The influence on an entire generation of filmmakers is obvious, and one need only cite Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs, with its non-linear narrative and its band of almost abstract criminals, to understand how deep the debt is.

Stanley Kubrick and the idea of criminality in his cinematic poetics go hand in hand with his pessimistic view of human nature. His criminals are almost never romantic or rebellious figures. They are professionals, technicians, or individuals attempting to impose a rational order on an inherently chaotic world. Johnny Clay is not a bandit, he is an architect who designs a system. His tragedy is believing he can control every variable, underestimating the corrosive power of greed, jealousy, and stupidity, embodied by the couple made up of the weak George and his greedy wife Sherry. In Kubrick's work, crime is often the product of a short circuit: the moment when a system (be it a robbery, a military mission, or society itself) collapses under the weight of its components' imperfections. Alex DeLarge in A Clockwork Orange is not just a thug, but the logical and violent response to a hypocritical and repressive society. Crime is not an anomaly, it is a constant, an inevitable eruption of chaos.

The influence of this film on the police and crime genre is therefore immense and goes beyond the simple cloning of archetypes. The Killing taught subsequent cinema a new way of storytelling, based on fragmentation and the manipulation of time. It introduced a tone of cold fatalism, an ironic distance that allows the viewer to admire the ingenuity of the plan while being fully aware of its imminent, catastrophic failure. And, above all, it left behind one of the most iconic and mocking final scenes in the history of film noir. The suitcase full of money that accidentally opens on an airport runway, with the banknotes being sucked up and scattered by the wind from an airplane's propellers, is the perfect visual metaphor for his entire filmography. It is the triumph of chance over control, of chaos over order, of the universe mocking the meticulous plans of men. Johnny Clay's final line, a whispered and resigned “What's the difference?”, is the requiem for every Promethean attempt by humans to dominate destiny. With this film, Kubrick didn't just shoot a heist, he defined the rules of an entire genre and then demonstrated, with surgical precision, that in the end, the only rule that matters is that the house—in this case, Fate—always wins.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...