The Searchers

1956

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

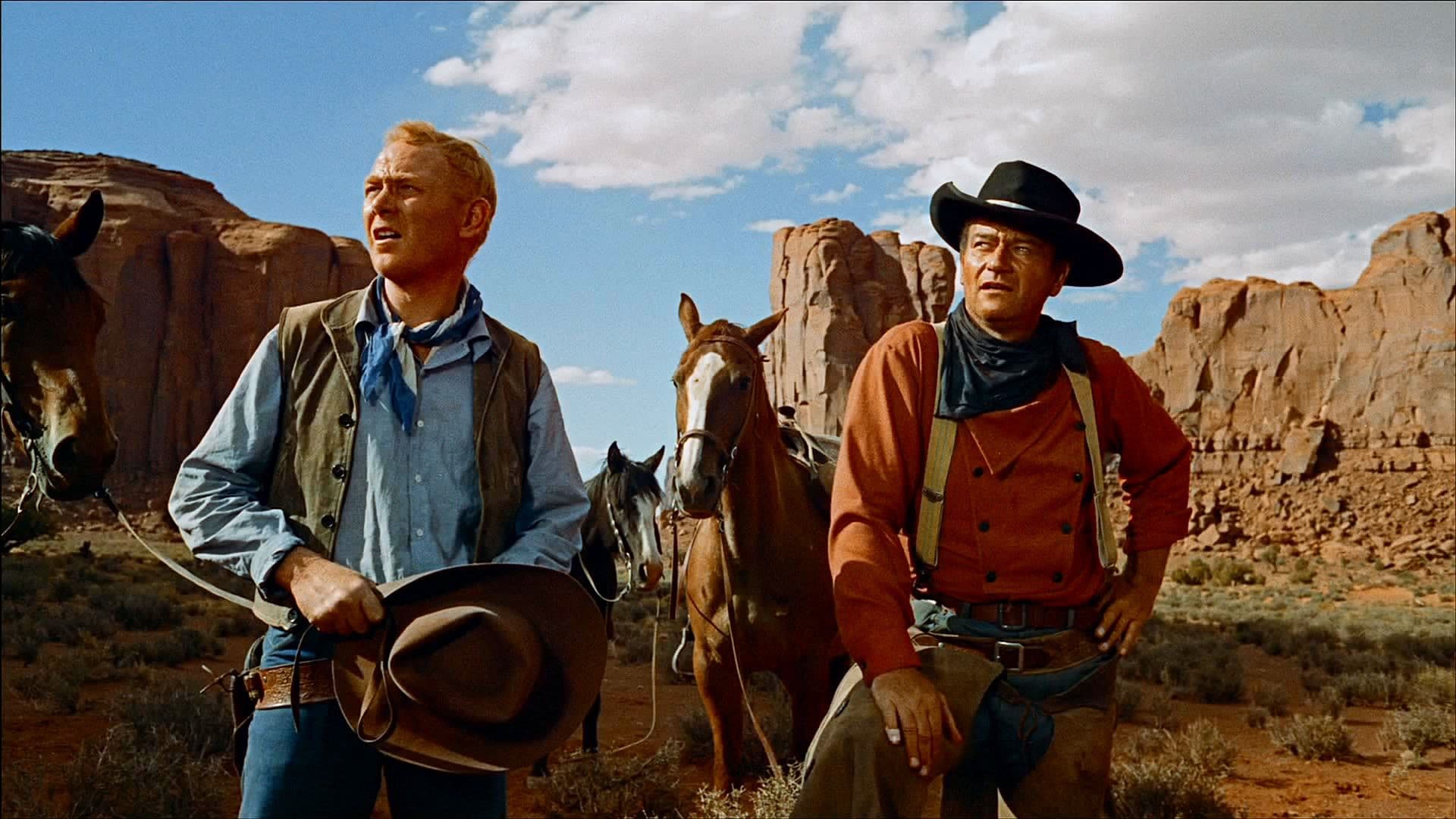

Director

One of Ford's most controversial films, due to the challenging portrayal of the main character. But also a work of immense beauty where man and nature interpenetrate, challenge each other, and discover one another, in a visual symphony that elevates the wild prairie, sculpted by wind and time, to a co-protagonist. The landscape of Monument Valley, which Ford had already immortalized in masterpieces like Stagecoach, is not merely a backdrop here, but a surface onto which the characters' tormented psychologies are projected, a horizon of solitude and relentless beauty that amplifies the epic and the drama.

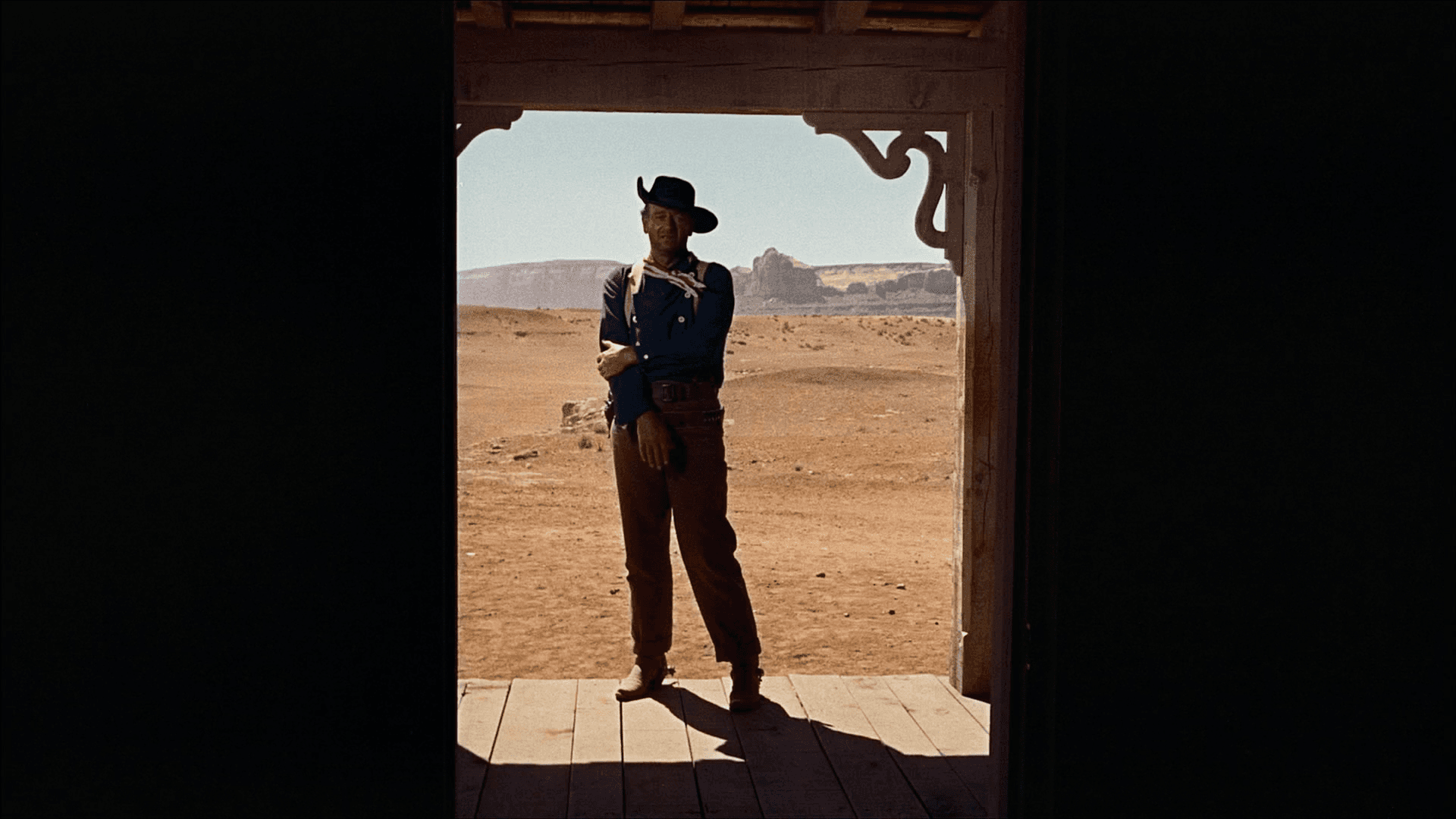

Based on a novel by Alan Le May, I cercatori (The Searchers) tells of a great search, or rather, an obsessive hunt. Ethan Edwards is an American Civil War veteran, a Confederate veteran whose return home heralds a rupture more than a reunion. His appearance from the desert dust, framed by an open door – a visual motif that will be iconically revisited in the finale – is the entry of a disturbing element. He sets out on the trail of a nomadic Comanche tribe, guilty of having abducted his young niece, Cindy, and of having wiped out his family.

His search, arduous on the trail, will become harsh and futile on a psychological level, where the man must confront his racism, no longer latent but visceral, and a misanthropy with often ironic undertones, yet a bitter, almost nihilistic irony. Ethan is not the untarnished and fearless hero of the classic western; he is rather a Homeric figure, an inverted Ulysses, condemned to eternal wandering, unable to find peace or a place to belong. His hatred for the "Indians," far from being a simple defense of "whites," becomes a pathology that devours him, transforming his rescue mission into a potential execution, reflecting a mind that does not contemplate the possibility of redemption or racial "contamination."

Ford's gaze is also cynical when he hints to the viewer that the hunt for the Comanches is no longer a pursuit to free the girl but to kill her (she has lived too long with the Indians and no longer has anything of the person she was before, according to old Ethan). This was not only a daring thematic step for the cinema of the time, but a radical deconstruction of the American foundational myth of "manifest destiny" and the civilizing hero. Ford, a master at exalting the frontier, here reveals its brutal contradictions, exposing the violence implicit in nation-building and the terror of "racial mixing" that fueled much of the ideology of the time. Ethan's fear that his niece has "become Indian" and can no longer be readmitted into white society reveals an uncomfortable truth about the moral foundations of that very society.

A gruff character, then, whose portrayal, as mentioned, proved difficult, both for the director and for the actor tasked with interpreting his complex character. John Wayne, an icon of the classic Western, delivers one of his most complex and nuanced performances in this film, shedding his aura of an immaculate hero to embody a man consumed by hatred, revenge, and a silent, almost mythological pain. It is an acting performance that marks a turning point in his career, demonstrating a dramatic depth rarely afforded to him. Ford, with his proverbial economy of direction and his ability to capture emotional essence in a few incisive glances, managed to extract from Wayne a portrayal of wounded and repressed humanity that still resonates today.

The final result is one of the most beautiful and compelling Western films ever, but above all a cinematic milestone, a work that has influenced generations of directors, from Martin Scorsese to Steven Spielberg, from George Lucas (the desolate landscapes of Tatooine in Star Wars are a clear homage to Ford's Monument Valley) to Wim Wenders. The final scene, with Ethan receding into the dust, condemned to remain an outsider, has become an iconic image, a universal symbol of alienation and solitude. That door, closing behind him, is not just a physical barrier but an insurmountable boundary that separates the man from the civilization he helped to found, a boundary that relegates him to a life of solitude, a ghost of an era that is closing.

The challenge is once again in favor of the one-eyed man behind the camera, who, as an invisible éminence grise, weaves the tapestry for his characters, guiding them through a landscape as much physical as it is internal. John Ford did not just direct a film; he created a myth and, simultaneously, dismantled it piece by piece, leaving us with a work of burning relevance, a profound inquiry into the mechanisms of hatred and the complex, often brutal, American identity. His direction, terse yet powerful, transforms a story of a search into a psychological odyssey, a journey into a darkness that resides as much in the human heart as in the unexplored folds of the continent.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...