The Shining

1980

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Jack Torrance is hired as the winter caretaker at the Overlook Hotel, a large hotel in a secluded area of the Rocky Mountains. A choice dictated by necessity and the hope of finding the quiet needed to dedicate himself to writing, but one that will prove to be a descent into hell.

A part-time writer, he decides to bring his family with him: his wife Wendy and his seven-year-old son Danny. Soon they will be completely isolated, cut off from the world by a relentless snowfall, and Jack will succumb to the venomous spell of that solitary and silent place, an evil entity that not only infuses paranoia but seems to draw upon and amplify his darkest impulses. The claustrophobia of infinite spaces, the echo of nothingness filling the immense halls, become a catalyst for a latent malaise, a chilling metaphor for the mental prison in which Jack is closing himself.

Indeed, years earlier, mysterious murders had occurred in the establishment, and Jack increasingly encounters strange apparitions that seem to restore the hotel to its former glory: the grand Hall comes alive with ghostly, festive yet sinister clients, and in this kind of parallel world from the past, Jack can calmly sip a drink at the bar counter while the mischievous bartender Lloyd, custodian of an unsettling infernal wisdom, amiably chats with him, providing pretexts and justifications for his increasing moral dissolution. These encounters are not mere visions, but an increasingly deep immersion into a distorted reality, where the line between the present and a bloody past becomes increasingly blurred, almost suggesting that the Overlook's history is not a mere memory, but an active and corrupting force.

Danny also encounters the same visions. Danny is a special child: he is a psychic and possesses the gift of second sight, the "Shining" that gives the film its title, and which allows him to see hidden things, to perceive the echoes of evil that permeate the hotel. His gift, far from being a blessing, proves to be a burden, making him prey to the most horrifying manifestations. In the labyrinthine corridors of the Overlook, Danny often sees two twin girls staring intently at him, spectral presences that recall the victims of a previous massacre and embody a childish yet deeply disturbing threat. The use of the Steadicam, employed so extensively for the first time, physically drags us behind Danny's tricycle, amplifying the perception of the vastness and isolation of the spaces, transforming the corridors into a labyrinth not only physical but also psychological.

One day, passing by room 237, Danny has a horrid apparition, and later Jack, entering the room to check, also sees a beautiful woman in the bathtub, literally liquefying under his hands and putrefying. This scene, a masterpiece of psychological body horror, is not just a visceral jumpscare, but a symbol of the corruption that the Overlook enacts: beauty transfigures into putrefaction, desire into repulsion, dream into nightmare. It is the point of no return for Jack, where objective reality gives way to the most grotesque hallucination.

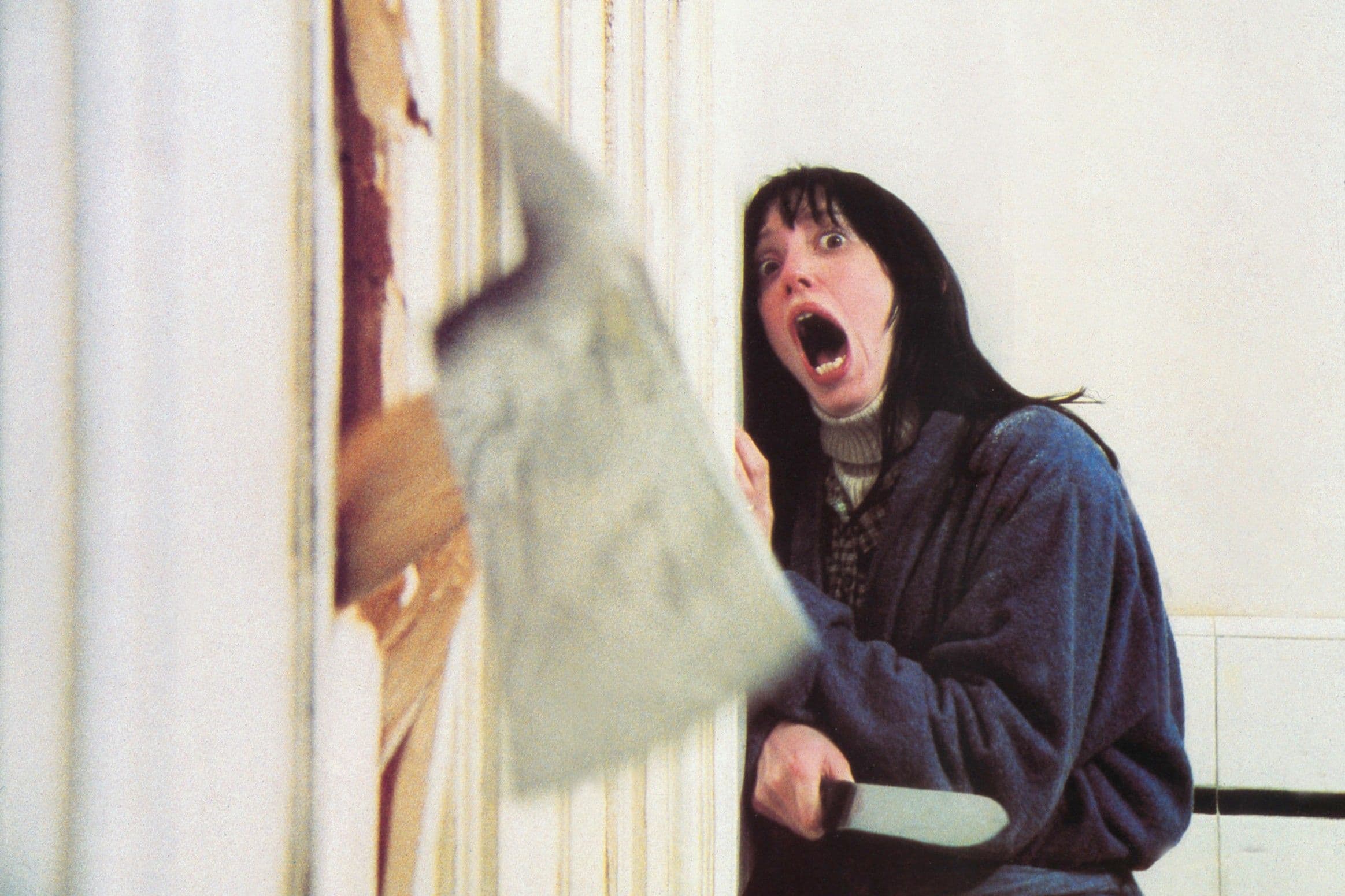

Jack becomes increasingly paranoid, and events will escalate until he is convinced that exterminating his family is the right thing to do, an action that, in his distorted mind, becomes almost a moral imperative dictated by the hotel's "guests." Meanwhile, Wendy, the embodiment of a frightened fragility that transforms into fierce determination to protect her son, approaches Jack's writings and leafs through the pages of his novel to realize with horror that they contain only the proverb "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" (which in the Italian version Kubrick changed to the equally iconic "Il Mattino ha l’oro in bocca") repeated endlessly throughout the pages. This is not just a sign of madness, but a chilling representation of Jack's creative sterility and his inability to produce anything but obsessive repetition, a mental loop that has consumed him, transforming artistic ambition into mere macabre automatism. Jack's madness is now manifest, and the macabre final dance can begin, a deadly dance between life and madness, love and hatred, family and destruction.

Kubrick tackles the Horror genre for the first time, and he does so in his own way, deconstructing and recoding it. For Kubrick, the demonic, esoteric aspect is relatively unimportant: true horror comes from man, from his self shattered into serial gestures, dispersed in an anechoic solitude, annihilated by paranoia. The hotel is not an entity that possesses Jack, but rather a magnifying glass that reveals and accelerates his pre-existing pathology, a predisposition to violence and abuse (as suggested by his past as an alcoholic and allusions to violence against Danny). The apparitions are not so much external ghosts as they are mental constructions of Jack, reliving the diabolical murders that occurred in those places, or projections of his own homicidal intentions, thanks to a manifest madness that drags him into a mental loop from which there is no escape. This interpretation elevates it far beyond simple supernatural horror, making it a chilling psychological study on the fragility of the human mind and the dangers of extreme isolation.

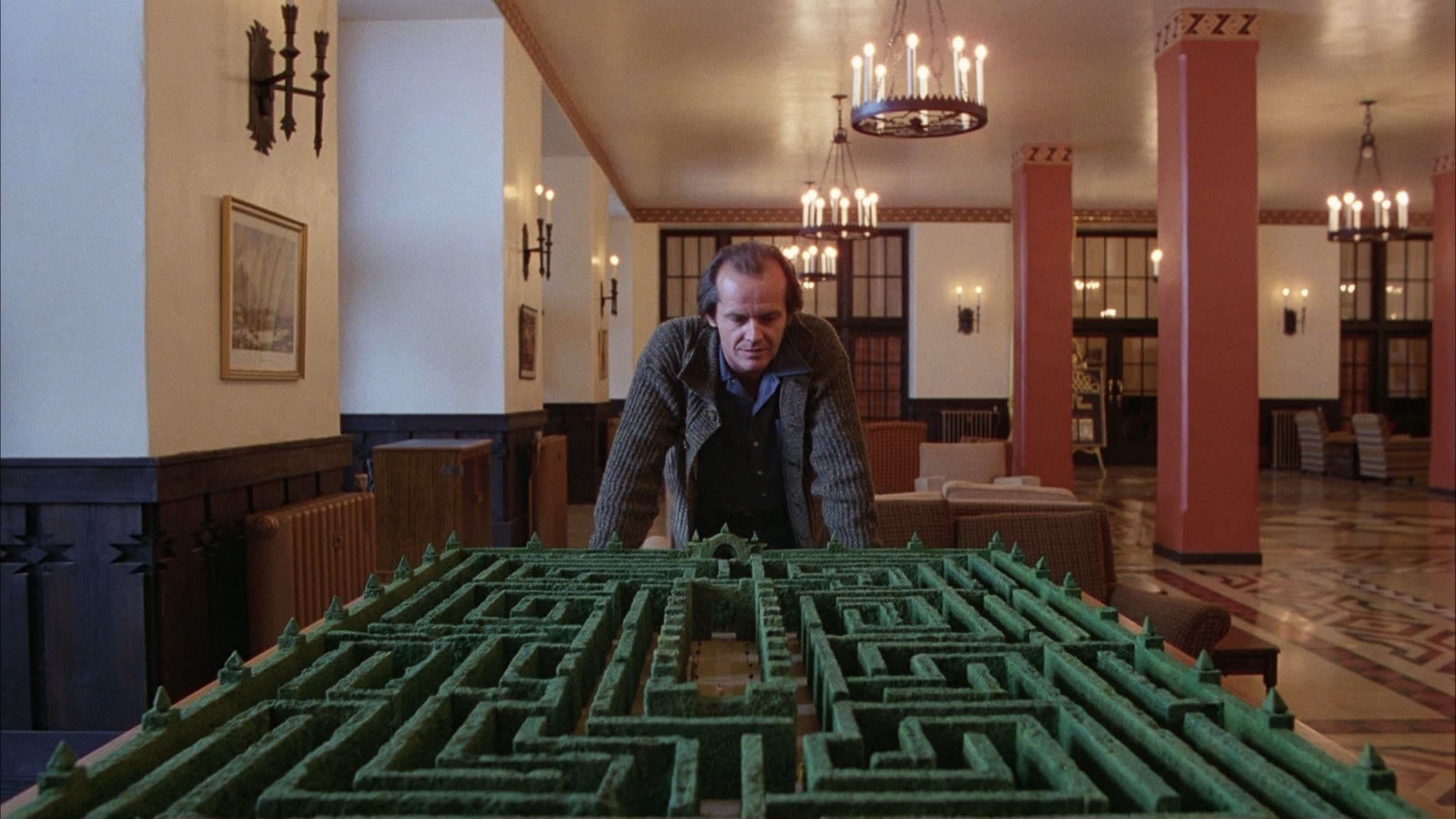

The Shining presents numerous essential traits of Kubrickian aesthetics: the deadly symmetry of objects and shots (the outdoor maze model, reflecting Jack's insane mental geometry; the hypnotic geometric shapes of the carpet in the corridors, true visual traps; the shots of the corridors themselves, always perfectly symmetrical with respect to the central vanishing point, creating a sense of claustrophobia and inevitability), the maniacal attention to the setting (the interiors were reconstructed in London with obsessive fidelity, allowing the director total control over every scenic and lighting element), the formal directorial perfection that translates into a visual and auditory experience of rare intensity. Every shot is a pictorial composition, every sound (from the chilling music of György Ligeti and Krzysztof Penderecki, which amplifies unease, to the almost unnatural silence that permeates the hotel) is calibrated to penetrate the viewer's defenses. The choice to shoot the film with an inordinate number of takes for each scene is not just anecdotal, but testifies to his maniacal pursuit of perfection, pushing the actors, particularly Shelley Duvall, to the brink of a nervous breakdown, thus reflecting the very anguish of their characters.

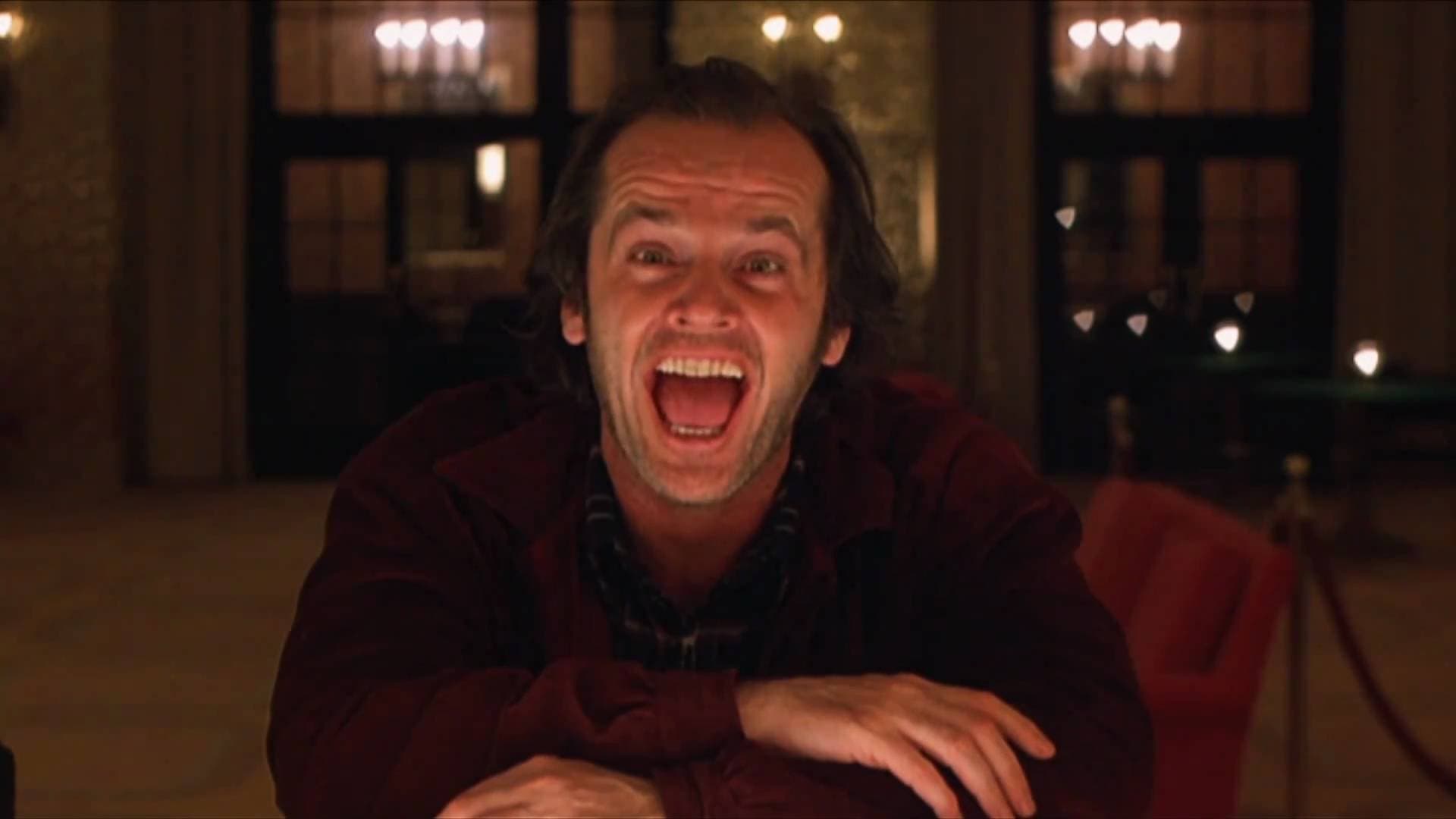

Some scenes have inoculated themselves into the collective imagination like indelible tattoos: such as the breach in the door through which a demonic and grinning Nicholson peers, eyes bulging, while intent on smashing open the bathroom door where Wendy has locked herself, with his famous "Here's Johnny!" which became a legendary improvisation. Or the already mentioned scene of the embrace of the putrefied body of the woman from room 237, an image of pure repulsion and horror. Or the elevator that, opening, floods the corridor with a surging river of blood, a scarlet wave that overwhelms the viewer, symbolizing all the unexpressed violence and the history of massacres that the hotel has absorbed and now erupts. Iconography from which it is impossible to escape and which constitutes an archetype that every director must sooner or later confront, a milestone that redefined the horror genre, demonstrating that true terror does not reside in the monster under the bed, but in the human psyche at the limit of endurance. A masterpiece of formal control serving devastating narrative and emotional chaos.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...