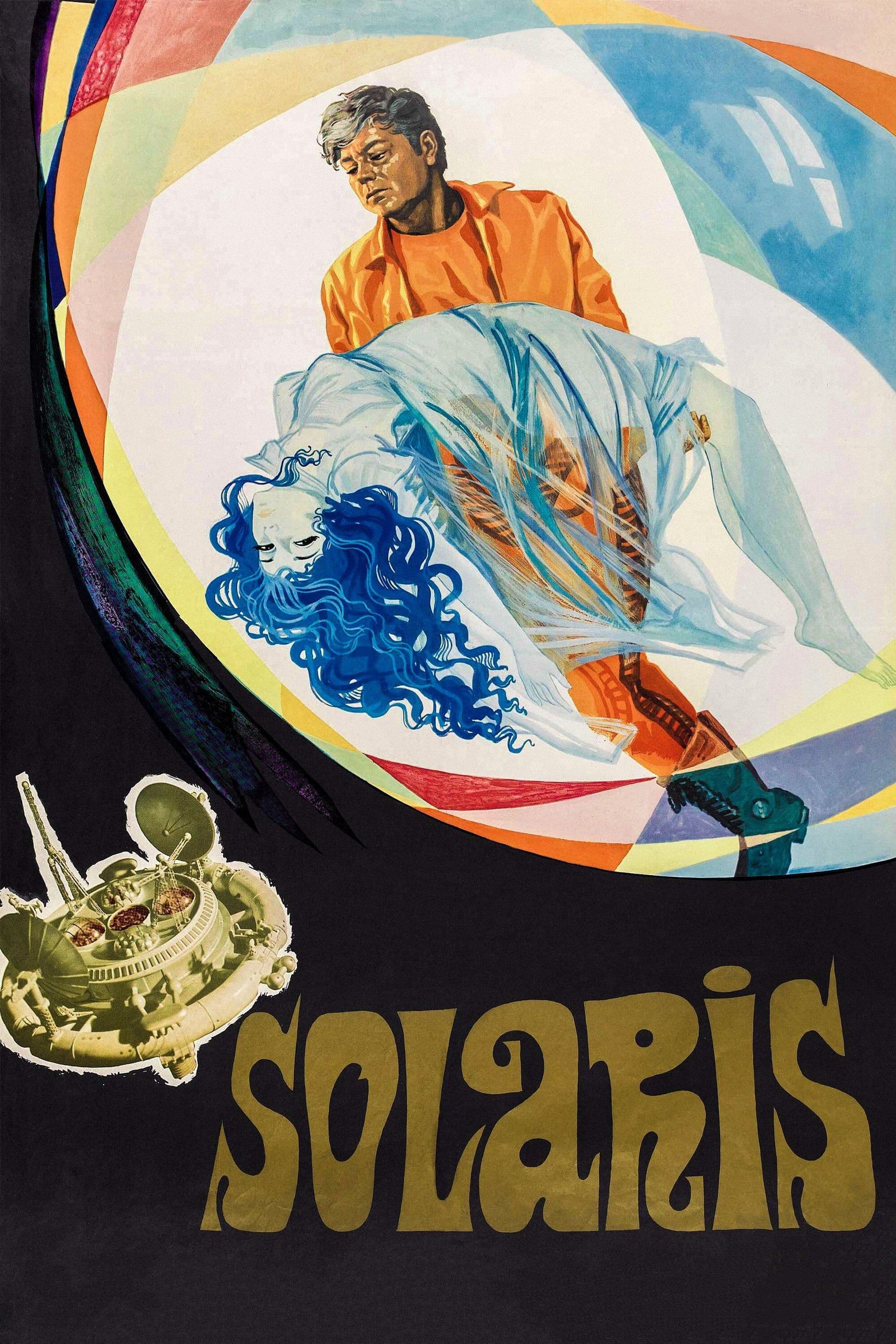

Solaris

1972

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

In Italy, this film was literally butchered by distribution: cut by 50 minutes and labeled as the Soviet answer to Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, a true abomination. An ill-fated juxtaposition, the result of cultural myopia that reduced art to sterile geopolitical competition, completely distorting the essence of two works, magnificent yet profoundly different. While 2001 was a glacial and almost mathematical exploration of cosmic evolution and artificial intelligence, a journey into the logical mind of the supercomputer HAL 9000 and an inquiry into human ontology in confrontation with the transcendent alien, Solaris reveals itself to be something entirely different: a suffocating immersion into the labyrinth of consciousness, an odyssey not towards the stars but into the very heart of the human being. Andrei Tarkovsky's own reaction to Kubrick's film, which he considered "sterile" and "aseptic," underscores this radical philosophical divergence between the Western vision of scientific progress and the profound spirituality and humanity that permeates the Soviet master's cinema.

A complex work centered on Stanislaw Lem's great novel, of which it renders every drop of melancholic disillusionment mixed with a growing anguish for the unknown. Although Lem himself was notoriously critical of Tarkovsky's adaptation, considering it too focused on human passions and too little on epistemological inquiry and the scientific unknown – for him, the film should have been a "paradigm of non-knowledge" – it is precisely in this "deviation" that the greatness and originality of Tarkovsky's work lie. He does not aim to replicate the novel's algid, speculative perfection, but rather to imbue it with a sorrowful soul, to root it in the fertile ground of regret and guilt, transforming cosmic mystery into an abyssal, heartbreaking inner drama.

The orbiting station around the planet Solaris has registered several problems culminating in the suicide of one of the three crew members. The other two members have also suffered some nefarious influence, showing clear signs of madness. Dr. Kris Kalvin, a renowned psychologist, is sent to investigate. He will realize that the planet is capable of manifesting human memories, giving them flesh and words. Not mere holograms or hallucinations, but real physical entities, "visitors" generated by the psyche, destined to torment and reflect the innermost fears and desires of their involuntary creators. He will thus have to confront his wife, who disappeared years earlier due to suicide, reliving the tremendous sense of guilt that binds him to the event. This is not merely a re-elaboration of grief, but an existential torture, a never-ending interrogation on the nature of reality, identity, and memory. He will begin a long journey through an undefined reality, interwoven with dreams and past memories, where the boundaries between what is tangible and what is merely psychic dissolve into a metaphysical agony.

A theme, that of Lem, very similar to Philip K. Dick's blurring of the real. Dream plane and real plane interpenetrate, giving rise to a kind of intermediate plane in which humans fiercely struggle to determine its topology. As in Ubik, one continuously has the distinct sensation of floundering in the mists of a dream, only to realize that one is fighting for one's life. This lability of the real, a stylistic and philosophical hallmark of both Dick and Tarkovsky, casts us into a limbo where perception is deceptive and truth elusive. It is an echo of the fragility of the human psyche in the face of the infinite unknown, a topos that traverses art and philosophy, from Platonic caves to post-Freudian anxieties about the "double" and memory as reconstruction. Tarkovsky, with his visual mastery and bold narrative experimentation, amplifies this disintegration of reality, immersing the viewer in a suspended, almost liquid-dreamlike atmosphere, where time itself seems to expand and contract in an ancestral breath.

His cinema is an almost tactile experience. The long, hypnotic sequences, the eloquent silences interrupted only by the patter of rain or the rustling of wind, the masterful use of color and monochrome that alternate like states of consciousness, create a cinematic universe where aesthetics indissolubly merge with spiritual reflection. Consider the film's opening minutes: the dacha immersed in lush greenery, the rain beating on the window, the stream – images of a living, pulsating land, of a primordial sensory memory, which violently contrast with the metallic sterility and cold geometries of the space station, transforming the film into a meditation on nostalgia, on the loss of what is human and organic. It is a journey not only through space, but through time and memory, a melancholic ode to the transience and fragile beauty of earthly existence. Every frame is a canvas painted with light and shadow, where detail takes on immeasurable symbolic value, elevating the narration to an almost mystical level and placing Solaris alongside other milestones of auteur cinema that investigate human interiority with equal depth, like certain works by Bergman or Bresson.

A film we do not hesitate to call a metaphysical masterpiece, a work that transcends genres to establish itself as a profound investigation into the nature of the human soul. It is not science fiction in the traditional sense, but an existential tragedy disguised as a space epic, an exploration of the depths of guilt, love, and memory. It is a work that grips you not with special effects, nor with spectacular action, but with the strength of its ideas, with its inexorable beauty and its piercing sorrow. Tarkovsky does not provide answers, but poses essential questions, leaving the viewer to wander in those "intermediate planes" of consciousness, to confront their own ghosts and unconfessable truths. A visual and intellectual experience that, more than fifty years after its creation, continues to resonate with a rare power, demonstrating how cinema can be a vehicle not only for entertainment, but for authentic, overwhelming revelation.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...