Cries and Whispers

1972

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

This work represented for Bergman the natural evolution of his speculative journey into incommunicability, which began with Persona, an existential inquiry that here condenses into a claustrophobic examination of the failure of the most intimate bonds. If in Persona the abyss was carved out of the silence between two women, here it multiplies and amplifies, taking on the complex and painful nuances of a family kaleidoscope destined for disintegration. And both the poetics and the narrative revisit the previous work and develop its warp, tinging it with a suffocating lyricism; here it is a lacerating portrait of human indifference, not merely an absence of feeling, but rather the inability or refusal to empathize, an ontological egoism that condemns one to the cruellest isolation.

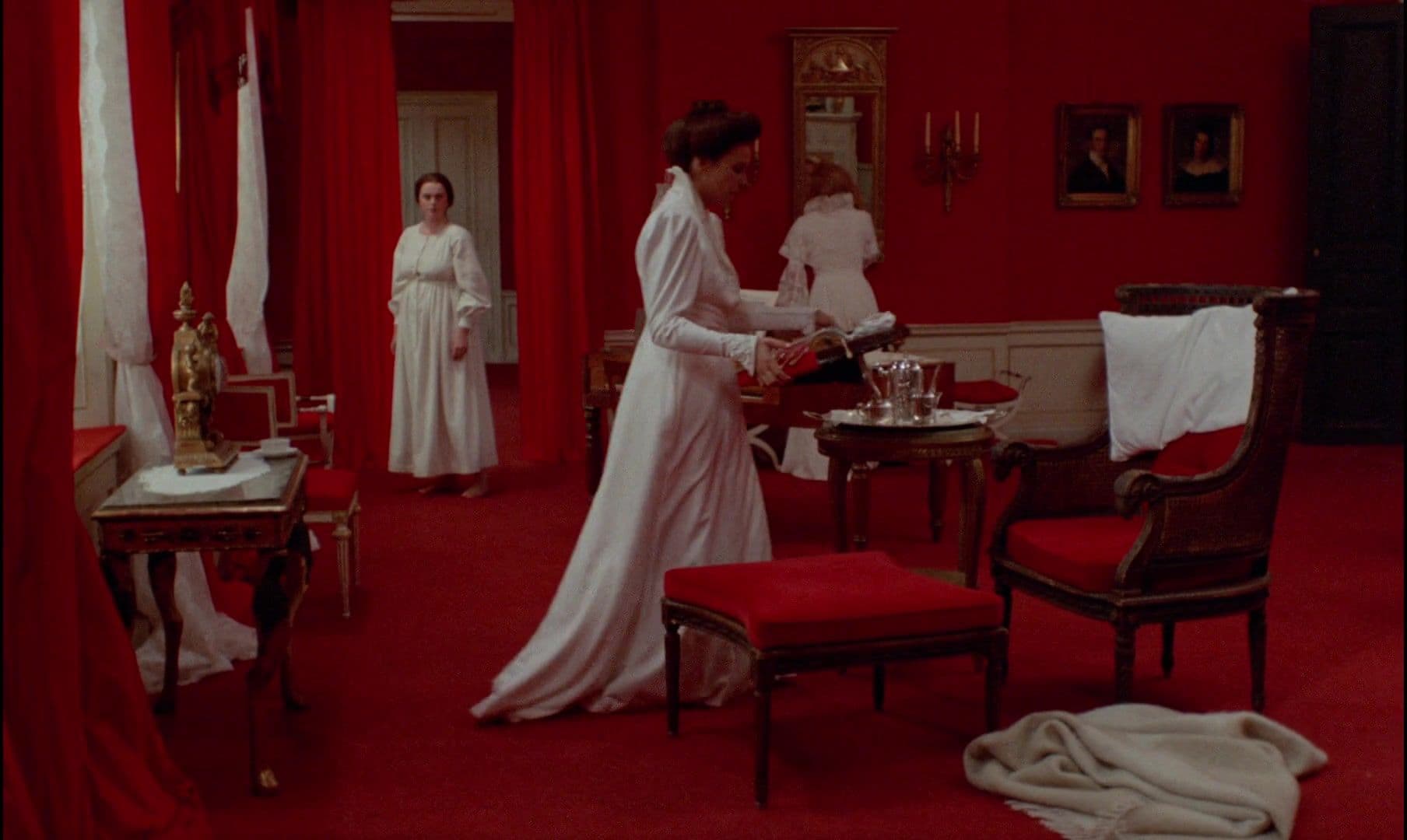

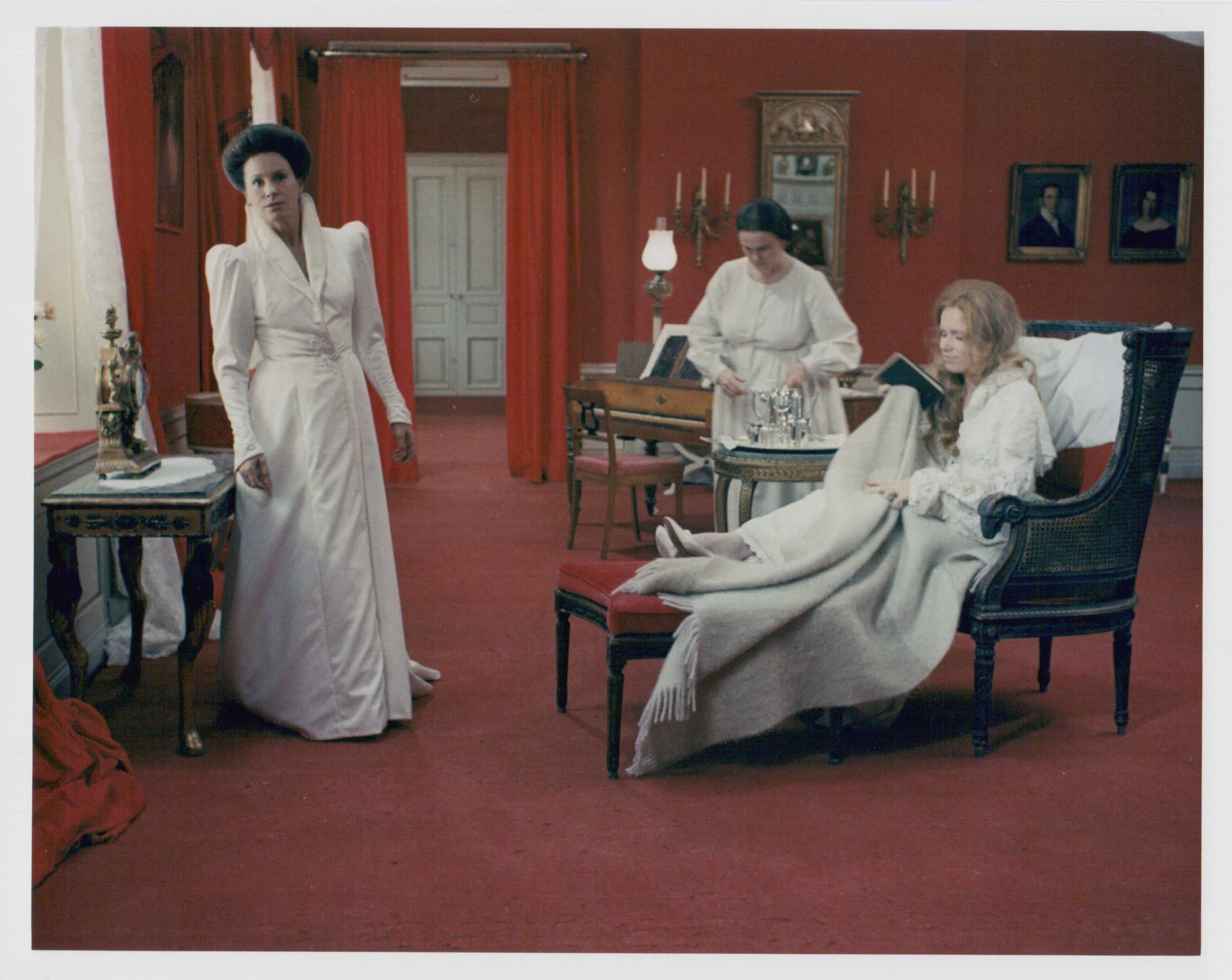

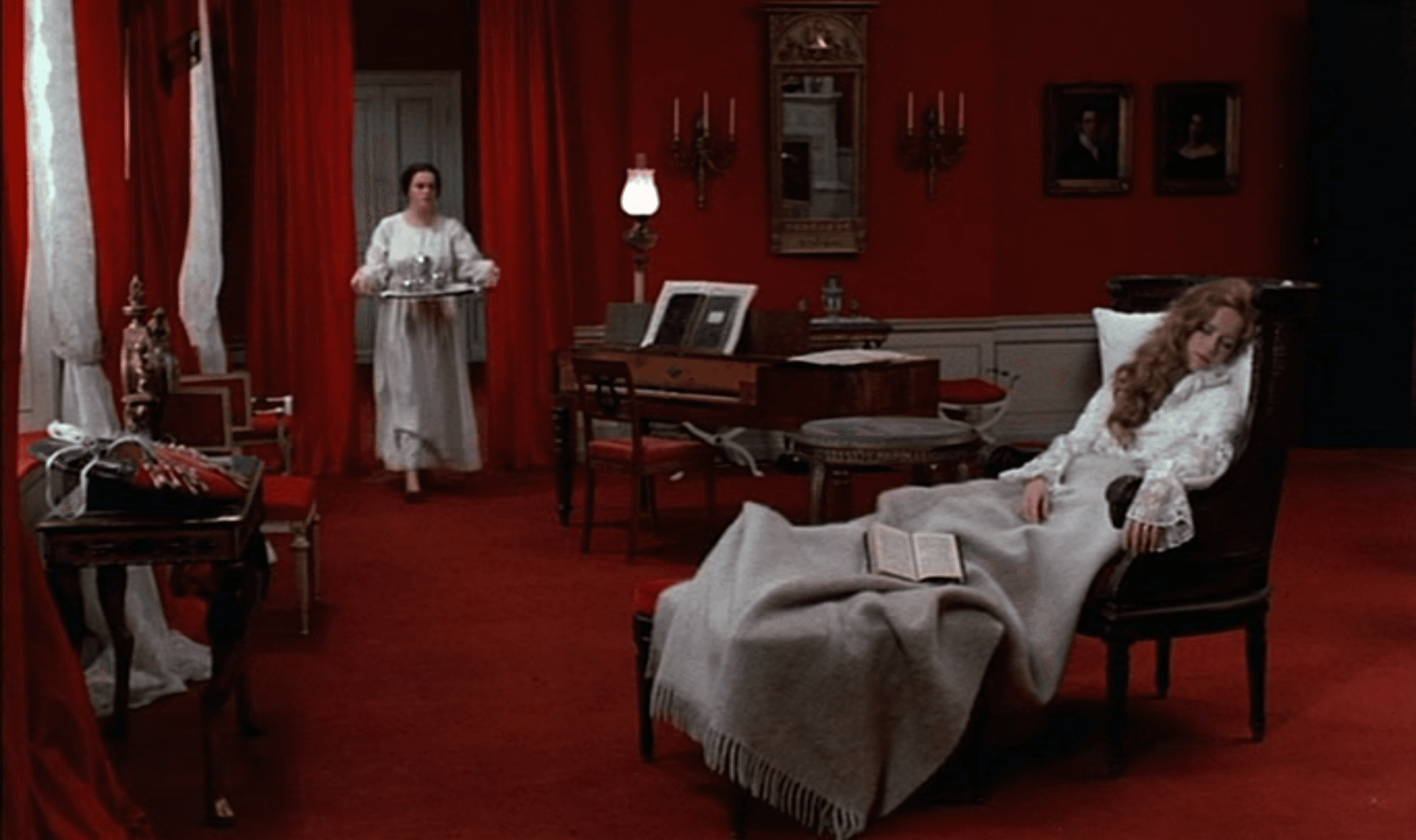

The story is set in a rural house in early 20th century Sweden, a setting that is not merely a backdrop, but almost a character in itself. The velvety tapestries and heavy red drapes do not offer warmth or comfort, but rather a sense of oppression and a gilded cage, a sumptuous yet suffocating shell that seals the drama. The early twentieth century, with its rigid bourgeois conventions and latent fin-de-siècle malaise, amplifies the feeling of a world where emotions are relegated to the unsaid, to furtive gestures or repressed explosions.

The young mistress of the house, Agnes, is dying of cancer and receives a visit from her sisters, Karin and Maria. It is not a comforting reunion, but a catalyst for the exacerbation of never-healed wounds. A gradual deterioration of human relationships among the three women will begin, a slow and inexorable erosion caused by a dialectical confrontation perpetually off-key, where every attempt at rapprochement clashes with invisible walls, erected by decades of resentments and misunderstandings. Agnes, even in her agonizing physical pain, becomes the mute center around which her sisters' neuroses revolve: the frigid and masochistic Karin, tormented by self-disgust that leads her to the most shocking self-mutilation, and the volatile and superficial Maria, prisoner of a vacuous hedonism that masks a deep existential void. Counterpointing their ruthless emotional aridity is Anna, the maid, a silent and maternal figure who, alone among them all, offers authentic compassion to Agnes, embodying a form of pure and unconditional love, almost primordial, in stark contrast to the glacial rhetoric of the mistresses.

The impression is that each of the women remains hermetically sealed within her own Monad, an explicit reference to Leibniz's philosophy, where individual substances are autonomous universes, without "windows" that allow direct communication with the outside. Despite their efforts, and sometimes even desperate pleas for closeness, they fail to communicate, condemned to an eternal inner solitude. Every attempt at connection is a failure: a rejected embrace, an unheard confession, a gaze that slips away.

It is a work where words become suffering, almost ethereal, unreachable, a vehicle of uncertainty and, often, of deception or veiled violence. Language, far from being a bridge, reveals itself as another wall, incapable of expressing unspeakable pain or the depth of resentment. Whispers are fragments of missed intimacy, cries are manifestations of an anguish that finds no outlet, echoes of an existence in which emotional truth is imprisoned. Silence is not rest, but the deafening reverberation of isolated hearts.

Bergman performs an extraordinary work from a cinematographic standpoint, an authentic aesthetic vertigo. Shot with unparalleled stylistic cleanliness and refinement, the film is a visual tour de force that transcends mere narration. The chromaticism, in particular, is a foundational and obsessive element: crimson red pervades every shot, from the walls of the house to the clothes, from spilled blood to the vibrant pulp of the soul. This color, often associated with pain, passion, life itself and death, becomes a visual metaphor for the maternal womb from which one is born and to which one returns, a symbol of familial blood that binds and suffocates, of Agnes's visceral pain and the intense emotional universe that the sisters cannot decipher. It is a red that bleeds and pulses, a living color in an environment of spiritual death, a striking contrast that evokes the expressionist palette of Edvard Munch or the intimate dramas of Scandinavian Symbolist painters.

The iconic scenes, borrowed from paintings, are living pictorial compositions: the image of the three sisters and Anna crying together in Agnes's bed, for example, recalls Renaissance Pietàs or classical sculptural groups, imbuing personal suffering with a universal and timeless dimension. The contrasts of shadows and light, masterfully sculpted by Sven Nykvist's cinematography, are not merely technical elements but hermeneutical tools: light reveals Agnes's purity and suffering, while shadows conceal Karin's darkest torments and Maria's superficiality. Everything is arranged with refined craftsmanship, a choreography of bodies, spaces, and colors that communicates more than any dialogue. Bergman, who personally financed a large part of the film's production, demonstrated not only an unwavering artistic vision but also a profound and courageous trust in his own poetics, risking everything to bring to life a work as intimate as it is lacerating.

The Swedish director delivers another masterpiece to us, and he does so with the bitter smile of one who knows how difficult it was to wrench it from his own poetics, from his own inner demons. Cries and Whispers is not just a film, but a cathartic experience, a brutal yet sublimated exploration of the human condition, of inescapable solitude and the desperate search for contact that too often remains a mirage. It is a testament to cinema's ability to probe the depths of the soul, leaving an indelible scar on the viewer and the awareness of the dizzying beauty that can emerge from the most authentic pain.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...