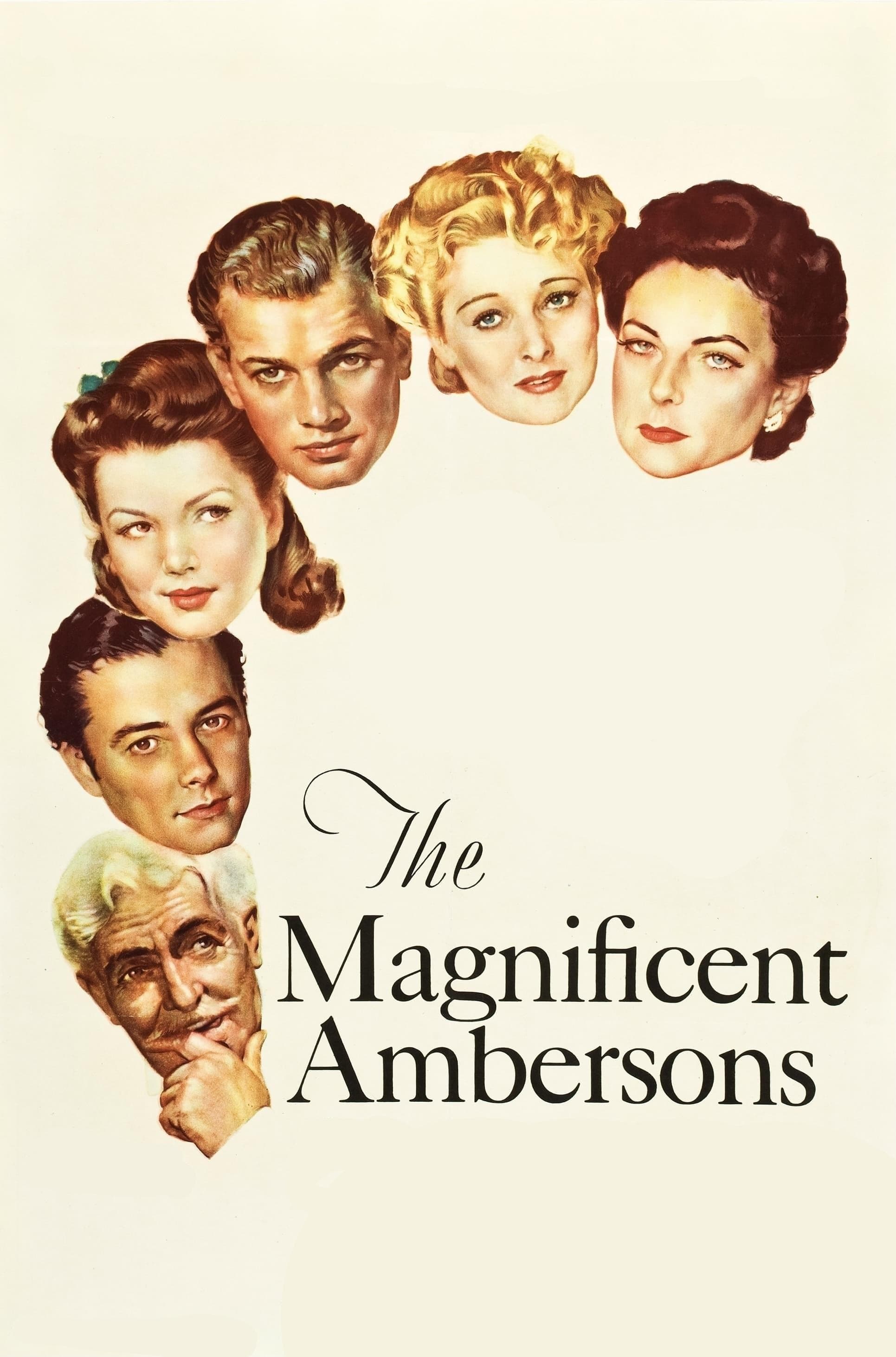

The Magnificent Ambersons

1942

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Based on a novel by Booth Tarkington, The Magnificent Ambersons is Orson Welles' second directorial effort, made amidst a violent conflict with the production company RKO, which would eventually cut over 40 minutes from the original footage (!!!). That conflict was not a simple contractual dispute, but an authentic artistic evisceration, a betrayal that shaped not only the perception of this masterpiece but also the entire trajectory of Welles' career in Hollywood. The brutal intervention by RKO, which was not limited to mere cuts but removed crucial sequences, rewrote the ending, and even commissioned new footage, transformed a monumental elegy into an open wound, an unfinished work that yet, miraculously, retains its power and charm intact. It is the story of a cinematic martyrdom, culminating in the legend of the lost reel, of the negative thrown into the sea, a tragic parable that has made The Magnificent Ambersons a totem of the struggle between artist and industry.

Despite this, it is a great film, it could not be otherwise, featuring an immense Joseph Cotten, an actor too often forgotten but of great acting verve. Cotten, here in his hieratic, almost sculptural composure, embodies not only the wounded "good boy" but also the modern visionary, a symbol of inexorable progress clashing with the immobility and arrogance of the old world. His performance is an exercise in subtle melancholy and dignity, an ideal counterpart to the furious, infantile egoism of George Minafer Amberson. His presence, so solid yet so vulnerable, is one of the emotional pillars of a work that pulses with regret and missed opportunities.

The story is a family saga: the Ambersons, a rich and powerful family unable to cope with their inexorable decline. At the heart of this saga is not just the chronicle of an economic or social decline, but the merciless examination of the vanity of pride, the blindness of privilege, and the dissolution of an era. Tarkington, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, had skillfully captured the nuances of turn-of-the-century America as it entered the industrial era, and Welles elevates this narrative to an epic fresco of Shakespearean proportions. The automobile, a symbol of progress for Eugene Morgan, is for the Ambersons the vehicle of their downfall, the deafening noise that drowns out the melody of their presumed greatness. Their house, imposing and lavish, progressively becomes a mausoleum, a labyrinth of shadows and dusty memories, reflecting the emotional claustrophobia of its inhabitants.

In the background is Eugene Morgan, a brilliant young man, in love with Isabel Amberson, who is set aside for an inept and insensitive suitor. Isabel, portrayed with ethereal beauty by Dolores Costello, is the fulcrum of this conflict, the woman whose repressed desires and duty-driven choices trigger a chain of fatal events. Her figure is an emblem of the Belle Époque woman, trapped between social conventions and personal urges, condemned to a surrogate happiness that translates into deep sorrow for herself and her loved ones, especially for her son George, the archetype of the spoiled and arrogant "brat," whose downfall is as inevitable as it is deserved.

But the story does not end with that rejection. The narrative continues, as ineluctable as the fate that befalls the Ambersons, showing the long-term consequences of decisions made and prejudices cultivated. Fate spares no one, not even the extraordinary Aunt Fanny Minafer, portrayed by a legendary Agnes Moorehead (whose hysterical kitchen table scene is one of the acting peaks in cinema history, worthy of a Tennessee Williams monologue), the bitter and frustrated spinster, whose bitterness is a painful reflection of denied opportunities and shattered dreams, a character who embodies the emotional claustrophobia of the family and the tragic nature of its end.

Orson Welles makes us understand the extent of his ability to delve into the psychological sphere of every "dramatis persona" involved in the narrative plot, presenting them to us laid bare, a soul of glass to be studied with merciless calm. This psychological penetration is made possible not only by the writing and direction but also by the visual and sonic magnificence. Welles, with his mastery, uses the deep focus he had experimented with in Citizen Kane, but here he adopts it with a darker, almost operatic intensity. Every shot is a baroque canvas of shadows and light (thanks also to Stanley Cortez's cinematography), where chiaroscuro is not merely a stylistic flourish but an emotional language, amplifying the desolation and isolation of the characters, trapped in the magnificent but decaying mansions of their arrogance. The famous backward dolly shot in the Amberson house, revealing the empty vastness and decadent elegance, is a visual metaphor for their inexorable evaporation. And then there is his warm and melancholic narration, which weaves the tapestry of time and memory, elevating the story to an almost mythological dimension, a requiem for a lost era. Despite the wounds inflicted by the production, The Magnificent Ambersons remains one of the most poignant and tragic meditations on time, memory, and the transience of greatness, a cinematic monument to Orson Welles' stifled but never entirely extinguished genius.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...