The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

1962

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Senator Ransom Stoddard returns to his hometown to attend the funeral of an old friend. This will be an opportunity to recall what he did for his town and how he achieved success, thanks in part to the killing of his nemesis, Liberty Valance.

This seemingly simple opening, in reality, conceals the pulsating heart of a work that delves deep into historical narrative and myth-making. The funeral itself is a solemn ritual, but its true function is that of a catalyst for a posthumous investigation into the genesis of a legend, forcing Stoddard to confront the abyss between his celebrated public persona and the hidden truth that forged him. His is not a mere nostalgic journey, but a pilgrimage to the roots of a constructed identity, where Ford, with his inimitable acumen, immediately introduces us to the central theme: the supremacy of necessary narrative over crude factuality, a concept that will resonate far beyond the dusty streets of Shinbone.

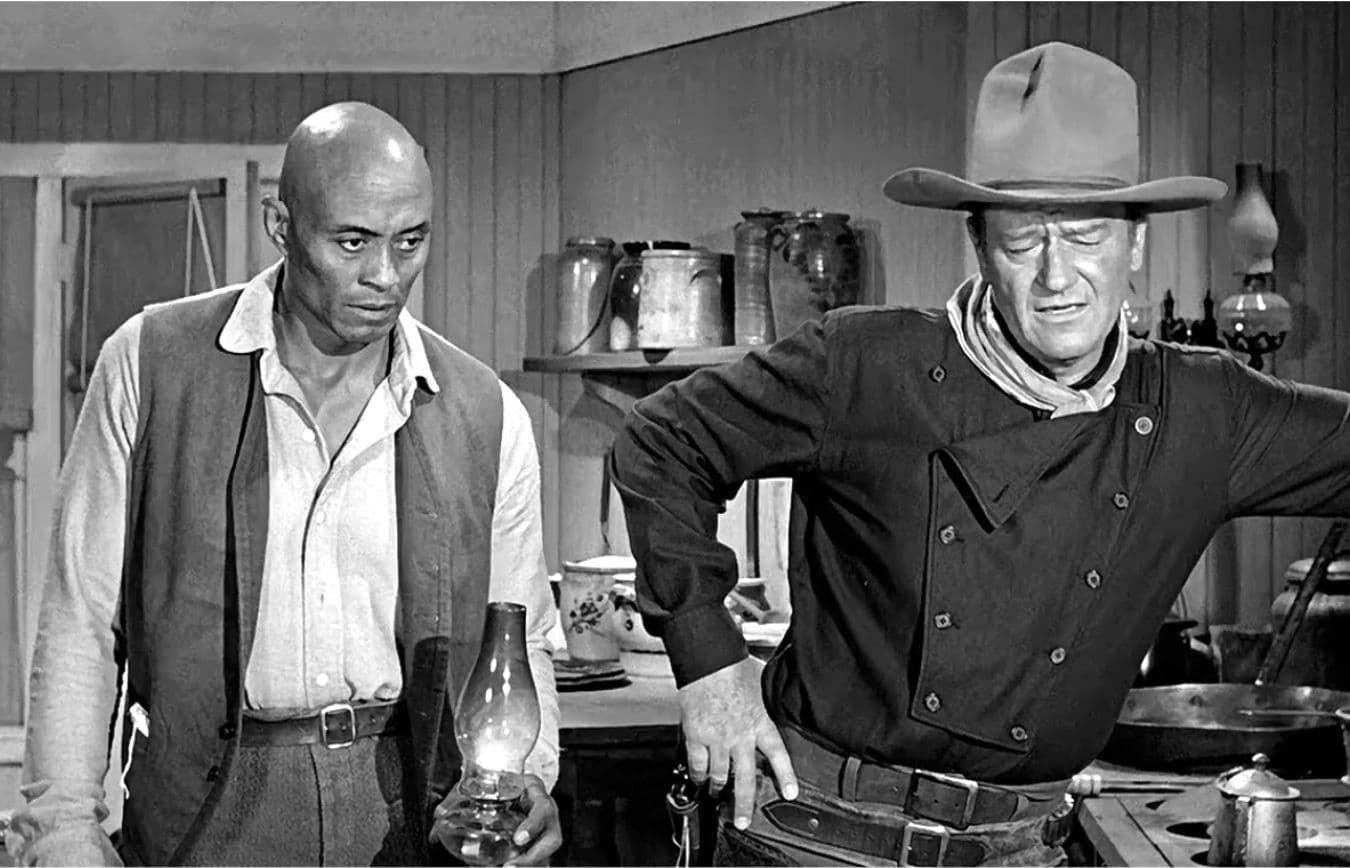

For the first time together, John Wayne and James Stewart participate in John Ford's mature masterpiece, a director who rewrote the American pioneering era in a modern key with careful psychological inquiry and a dynamic, empathetic conception of imagery. The presence of these two giants of American cinema – John Wayne, the emblem of the rough and pragmatic West, and James Stewart, the idealistic and unarmed intellectual – is not a mere casting gimmick, but an ideological collision orchestrated with almost Shakespearean mastery. Their interaction embodies the film's central conflict: the epochal transition from a frontier governed by the gun and brute force to the advent of law, democracy, and civilization. Ford, having reached the pinnacle of his art, largely abandons the boundless and iconic panoramas of Monument Valley to confine his characters to almost claustrophobic interiors, a choice not only pragmatic (the film was shot entirely in a studio, an anomaly for the Maestro) but deeply symbolic. The external vastness of the West gives way to the intimacy of consciences and human relationships, where the true drama unfolds, far from gunshots and horseback rides. The Fordian psychological inquiry here is not a mere embellishment, but the beating heart of a work that deconstructs the foundational American myth, revealing its scars and inevitable compromises.

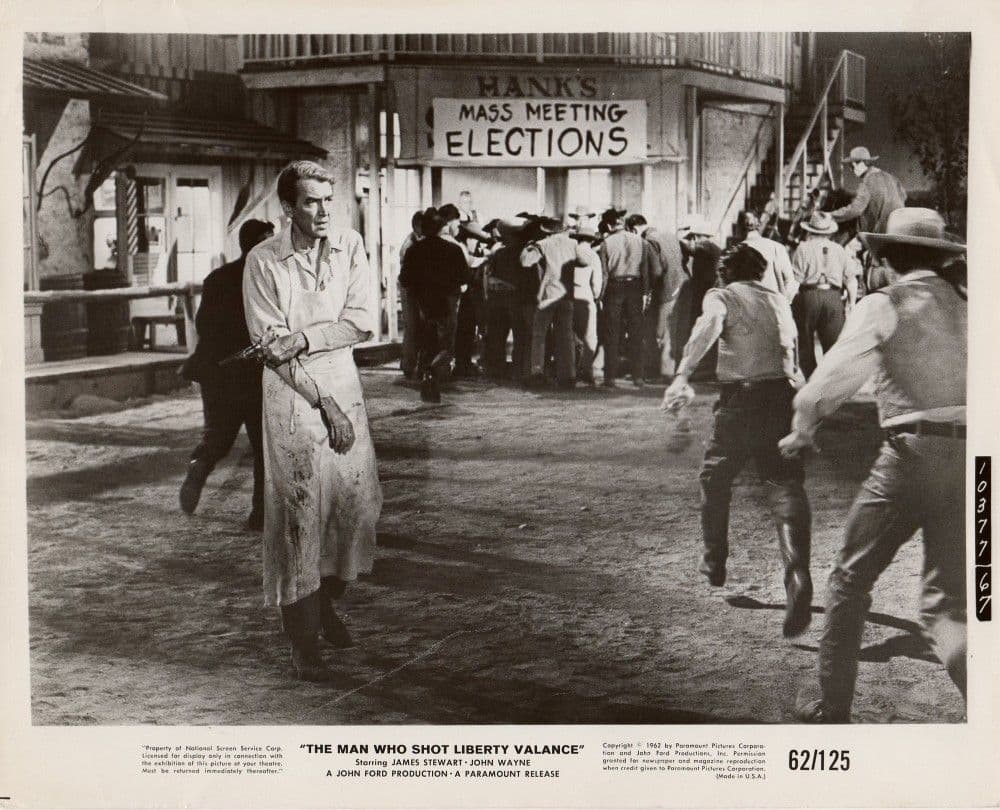

A twilight western where action is carefully and soberly doled out and where the Maestro prefers to have characters interact through tense dialogues and dialectical confrontations that gradually reveal each one's emotional sphere. This "twilight" is far more than a simple genre label; it is the stylistic and conceptual hallmark that permeates every frame. We are at the sunset of an era, that of gunfighters and lone heroes, and at the dawn of another, governed by ballots and legislative acts. Ford doles out action with the parsimony of a true playwright, knowing that the real duel is not fought with gunpowder, but with sharp words and eloquent silences. The dialectical confrontations between Stoddard, the lawyer who brings law and education, and Tom Doniphon, the man of the gun and the land, are true philosophical clashes. They are not just characters, but archetypes of antithetical principles destined to collide, with one having to sacrifice himself so that the other, and with him progress, can flourish. It is a moving elegy for a disappearing world, a lament for heroes who, despite building the foundations of civilization, are destined to remain in the shadows, their greatness concealed so that the light of modernity can shine, even if upon a necessary lie.

For the first time, Ford makes extensive use of flashbacks, and it is precisely with this technique that he reveals throughout the story the true events that led to the killing of Liberty Valance and the connection between every character involved. The massive adoption of flashback, in fact, marks a bold turn in Fordian poetics, giving the film a narrative structure that closely resembles the labyrinthine architecture of Citizen Kane in its quest for a foundational truth. It is not a simple nostalgic evocation, but an almost forensic investigation, an archaeological excavation into memory that unearths layers of convention to reach the nuclear truth – and simultaneously, to confirm its inherent malleability. Every fragment of the past, every testimony, contributes to deconstructing the myth of Ransom Stoddard, revealing its genesis not as an act of solitary heroism, but as the result of collective sacrifice and a providential omertà. This narrative device is the engine that pushes the film beyond the boundaries of the traditional western, transforming it into a keen examination of the nature of history, the formation of legends, and the inevitable compromise between what happened and what was told for the greater good of the community.

Thanks to these devices, Liberty Valance remains an atypical work in Ford's filmography, certainly fascinating in its creative effort to innovate the genre through atypical canons, which make this film a sort of wonderfully decadent work. "Wonderfully decadent" is the exact definition of a work that, while celebrating the birth of a civilized and democratic nation, bitterly laments the loss of innocence and the wild romanticism of the frontier. It is a bitter reflection on the necessity of sacrificing "true" heroes – those forged by the harsh law of survival – in the name of a cleaner, more edifying, and presentable image for progress. The film's iconic line, spoken by an elderly newspaper editor at the climax of the revelation, "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend," is not a cynical warning, but a pragmatic observation on the art of governance, the power of narrative, and the fundamental human need for heroes, real or fictitious. It is a statement that delves deep into the American consciousness, exploring the need for foundational narratives, even when they diverge from the raw, uncomfortable truth.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is not just a western, but an almost Pirandellian examination of identity, social masks, and the price of progress. In an era when the western was beginning its downward trajectory, Ford not only boldly innovated it but also wove its eulogy, with a dry realism and an intrinsic melancholy rarely found in genre works. The film stands as a monument to moral complexity, a work that transcends its own boundaries to interrogate the very nature of historical memory and the sacrifice necessary to forge a civilization. Its atypicality lies precisely in this courageous intellectual honesty, in the refusal to embellish a reality that, however cruel, was the true matrix of modern America. It is a masterpiece not only for its technical execution and the brilliance of its performances, but for its ability to make us reflect on what we choose to believe, and why, in the vast and shifting landscape of human history, and on how the foundations of a nation are sometimes built not on truth, but on the inescapable beauty of legend.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...