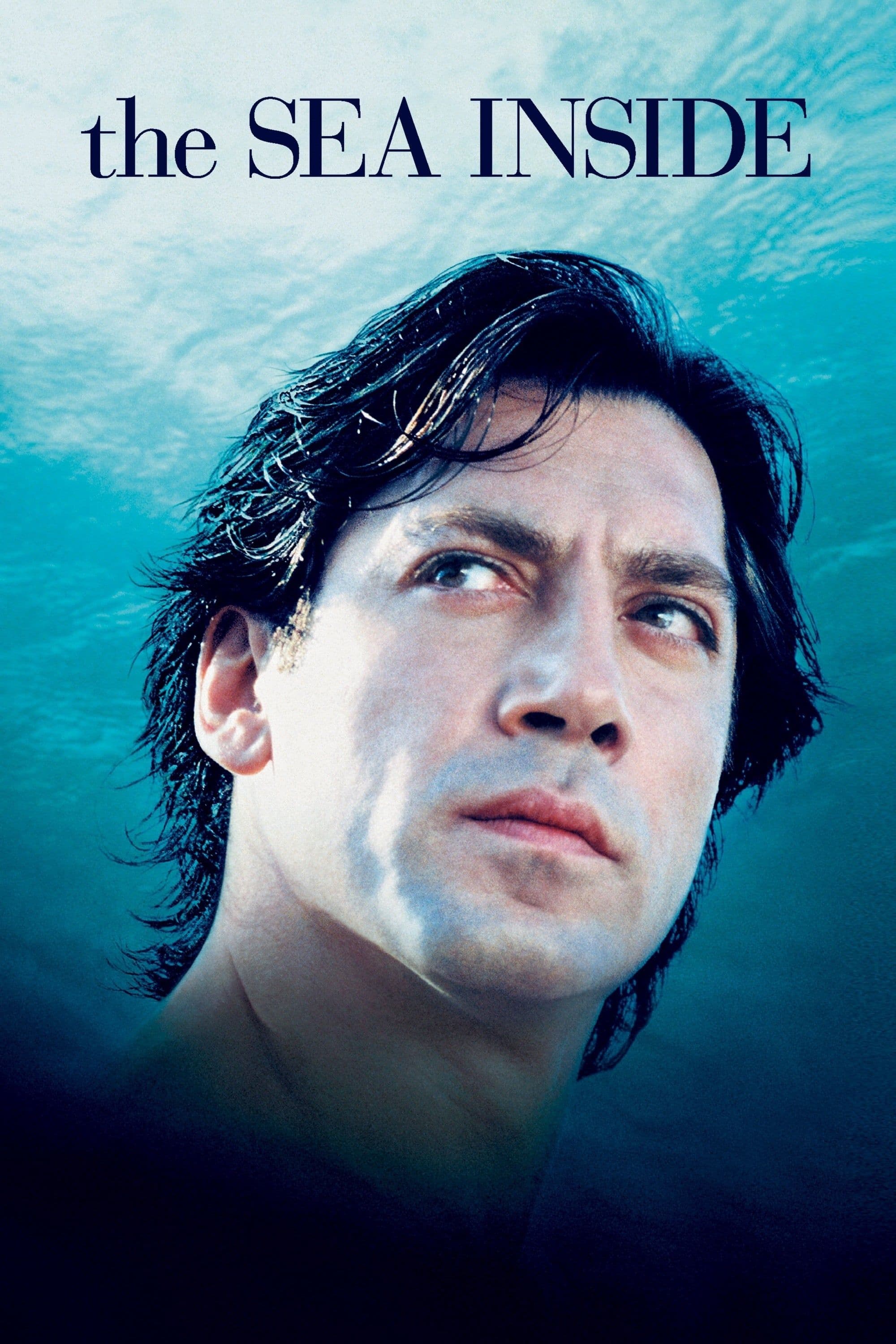

The Sea Inside

2004

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A film that deeply moves with its delicate poetry, presenting a subjective vision of a man's disability that inevitably stirs, unveiling his oceanic suffering. This is thanks also to Amenábar's impalpable direction, and ultimately, it succeeds in touching the viewer through Javier Bardem's magnificent, graceful performance. It is not merely the narrative of a tragedy, but an immersion into the soul of those who experience it, an exploration that avoids the pitfalls of pietism to embrace the complexity of existence. Amenábar’s hand, in this, is sublime: almost invisible, it merely guides the gaze, allowing emotional depth to emerge from the truth of the characters and from the raw, yet always dignified, representation of an extreme condition. It is a direction that does not judge but embraces, that does not sensationalize pain but renders it tangible, almost breathable, through a visual aesthetic of rare elegance and a skillful use of silence and light. Bardem, for his part, does not merely impersonate, but embodies Ramón Sampedro, blending his own physicality with the character's immobility in an acting tour de force that goes far beyond mimicry, reaching heights of empathy and understanding rarely seen on screen. Every subtle expression, every flicker in his eyes, every vocal inflection becomes a vehicle for a boundless inner universe, confined within a body, yet capable of a disarming spiritual freedom.

The Sea Inside is the precious testimony of a man and his suffering that becomes a poetic abyss, a melancholic counterpoint to the wonders of life and the infinite tension towards these beauties. In an era dominated by frenzy and the imperative of uninterrupted productivity, Amenábar's film emerges as an oasis of reflection, an invitation to contemplate the intrinsic value of existence even when it is burdened by an unbearable weight. It is not a celebration of suffering, but rather a lucid recognition of the boundaries between life and death, between the freedom to choose and the condemnation to immobility. It is a cinematic essay on self-determination, imbued with a dignity that elevates the ethical debate above sterile polemics, placing the individual and their inalienable right to decide their own destiny at its center. The film, in this sense, aligns with that artistic and literary tradition which, from Leopardi to Camus, has plumbed the absurdity of existence and the search for meaning even in nonsense, without ever succumbing to nihilism, but finding its redemption in poetry itself.

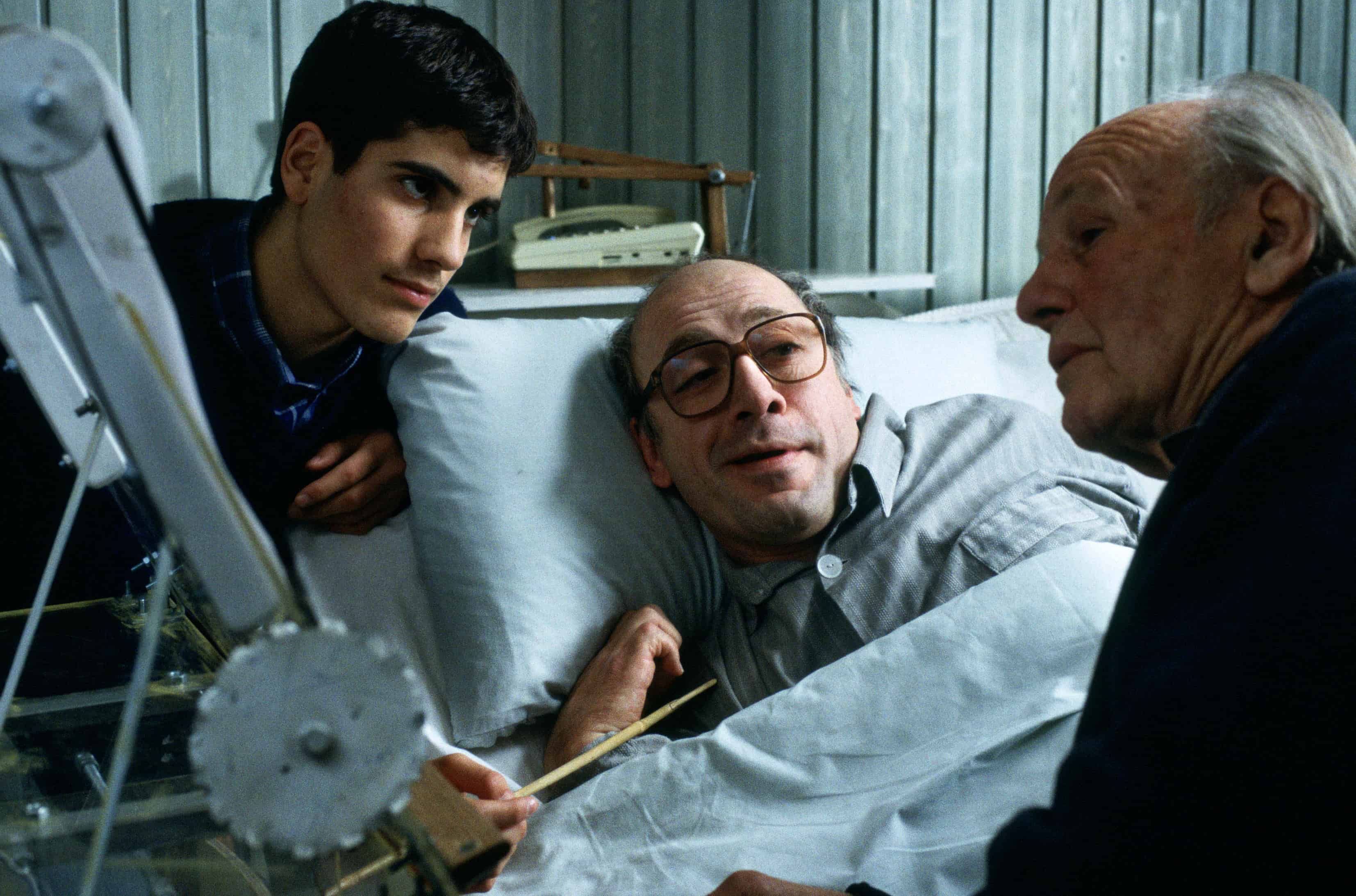

A film that transforms man, his desires, his inescapable affinity for life into an enchanting elegy. The story is that of Ramón, quadriplegic for over twenty years due to a dive into the sea. But the most extraordinary aspect of its narrative lies not so much in the account of facts, as in the way Amenábar manages to transfigure the biography of Ramón Sampedro – a real figure whose battle for the right to a dignified death shook the foundations of Spain and beyond – into a universal parable about the human condition. His is not a story of pure resignation, but rather the odyssey of a spirit that, though immobilized, never ceased to travel, to love, to dream. The choice not to indulge in didactic flashbacks about Ramón's previous life, except through dreamlike fragments, reinforces the idea that his true existence has moved elsewhere, into that inner dimension that cinema, with its evocative power, can render palpable.

Ramón's life is punctuated by small events that brush against him and affect him, like the sound of the sea, the color of the sky, the crash of lightning, glimpses of a blue that he carries within him like a seasoned poet. His room, more than a prison, transforms into a privileged observatory of the universe, a microcosm from which Ramón distills his deeply personal vision of the world, filtered through the prism of an extremely keen sensibility. In a striking parallel with works like Julian Schnabel's The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, where the protagonist, also immobilized, communicates through the blink of an eyelid, The Sea Inside immerses us in the abyssal depth of a mind that, though confined, remains the only true space of freedom. Ramón wishes to die and seeks in euthanasia the final solution to his immense suffering. This request, far from being an act of desperation, is presented as the ultimate expression of his will, a gesture of consistency with his own philosophy of life, an act of self-determination that directly confronts social, religious, and legal conventions. The film does not merely expose the ethical dilemma, but animates it through the figures revolving around Ramón: the lawyer Julia, who fights for his rights, and Rosa, the woman who falls in love with him and tries to convince him that life, in any form, deserves to be lived. These are contrasting voices that reflect the complexity of a debate that still tears at consciences today, but which the film handles with rare delicacy and intellectual honesty, avoiding easy Manichaeism.

Some scenes remain memorable, like Ramón's flight from the open window, soaring low over forests, valleys, and mountains, to the notes of “Nessun Dorma,” a daydream that gets under the skin; and through that flight, the suffering of a man forced into cruel bodily segregation, yet free to soar with his mind and soul, is palpable. This sequence, which alone would make the entire film worth watching, is a masterpiece of aesthetics and meaning, a crystal-clear example of how cinema can transcend reality to express the most intimate truth of the human spirit. The air caressing his face, the immensity of the landscape beneath him, the lyrical ascent of Pavarotti's voice: everything converges to create a moment of pure catharsis, a hymn to the freedom of the spirit that nullifies, albeit briefly, the tyranny of the body. It is an image that imprints itself on memory, a powerful reminder not to confuse life with mere physical existence, but to recognize it in the capacity to dream, to love, to imagine. Ramón's verses are, in this sense, the mirror of an indomitable spirit constrained by captivity yet still swollen with love: “Your gaze my gaze, like an echo repeating, wordlessly: deeper, deeper, beyond everything, through blood and marrow. But I always wake up, while I always want to be dead, so that I with my mouth may always remain within the net of your hair.” In these words, steeped in an almost ancient lyricism, resonates the irrepressible desire for a profound connection, for an intimacy that transcends the corporeal, testifying to the persistence of love and passion even in the face of the inevitability of limitation. A film that does not merely tell a story, but creates a poetic dimension that endures long after viewing, pushing the spectator to confront their own concepts of life, freedom, and dignity.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...