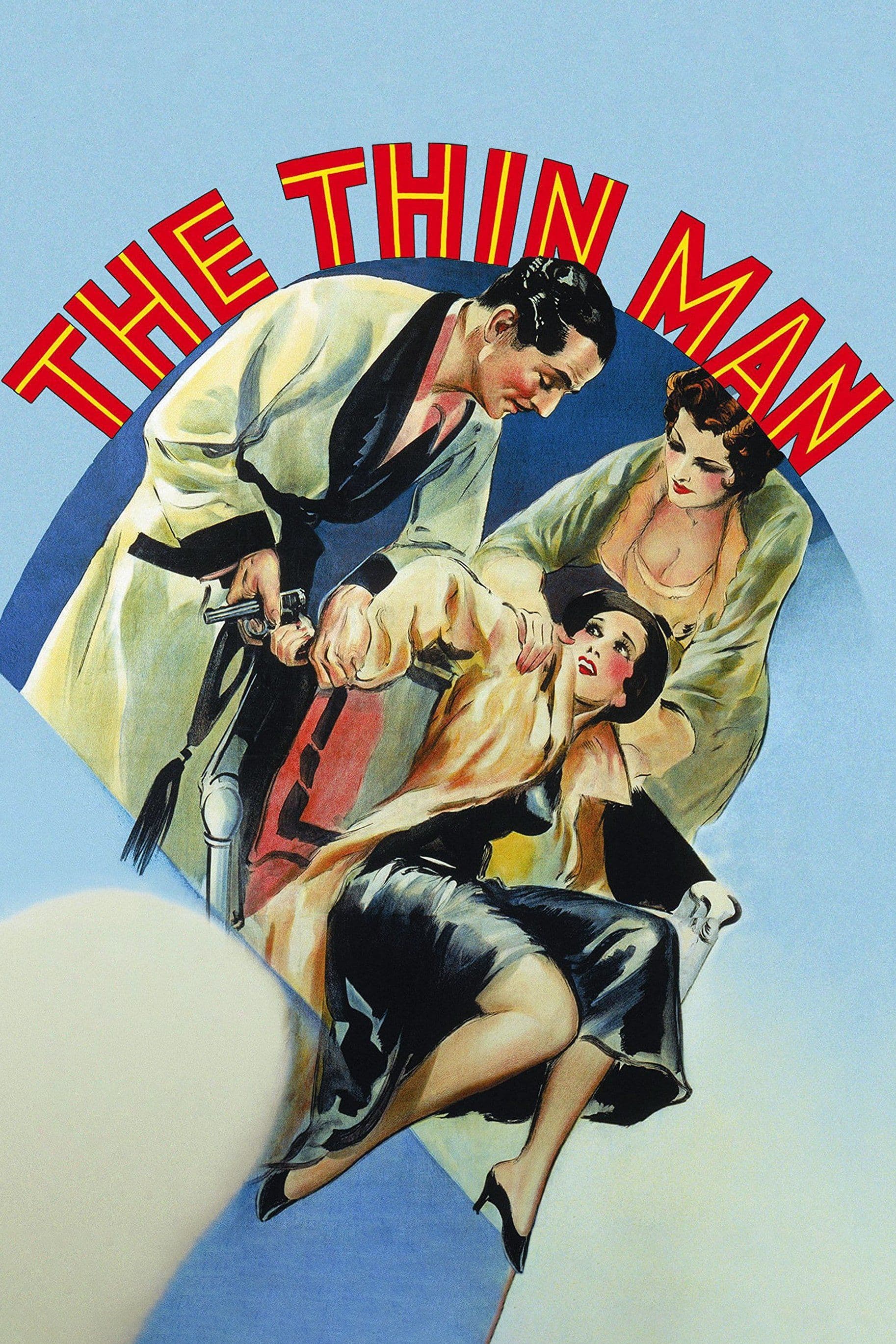

The Thin Man

1934

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The film is a faithful paradigm of its creator's modus operandi: Woody Van Dyke. And so, from a tight, breathless noir plot emerges the art of a director who was nicknamed "one take" for his habit of shooting a film almost in a single take (he took 12 days to shoot The Thin Man). This approach, almost counter-current to the meticulousness of other masters, was not mere production pragmatism, but a true creative philosophy. Van Dyke firmly believed that the energy and spontaneity of performances could best be captured in a few, intense takes, avoiding the excessive analysis and rigidity that could result from endless repetitions. This methodology imbues The Thin Man with a palpable vitality, an almost theatrical freshness, where the lines and reactions between actors seem to arise in the very moment, with an alchemy difficult to replicate in more deliberate productions. The film's fast pace and narrative fluidity are indebted to this "single take" aesthetic, which perfectly matches the protagonists' mental agility and the rapid succession of events.

The Thin Man is not just a detective film; it's a cinematic experience that brilliantly blends the thrill of mystery with the elegance of sophisticated comedy, all seasoned with a touch of Hollywood glamour. Based on Dashiell Hammett's novel of the same name, the film introduces us to the fascinating world of Nick and Nora Charles, a detective couple portrayed with irresistible charm by William Powell and Myrna Loy. Theirs is a performance that transcends mere acting; it's a dance of glances, gestures, and intonations that defines an unprecedented marital and professional understanding on screen. With brilliant dialogue, a refined atmosphere, and a touch of irony, the film captivated audiences and critics, giving rise to a successful series of sequels (no less than five!) and profoundly influencing film noir for years to come. The adaptation, while taking some liberties with Hammett's darker tone – he was, after all, the father of hardboiled with his disillusioned and cynical figures – manages to capture the essence of the intrigue and infuse an unprecedented lightness, almost a champagne bubble in a genre that would soon be steeped in shadow.

The plot, set during the Christmas holidays in dazzling 1930s New York, immerses us in an intricate and suspenseful investigation. This festive setting, rather than diluting the intrigue, enhances its contrast, creating an aura of superficial carefree-ness that conceals the dark underlying plots. Nick Charles, a former private detective now devoted to idleness and life's pleasures, finds himself reluctantly involved in the investigation into the disappearance of a scientist, Clyde Wynant. The scientist's daughter, Dorothy, asks Nick for help finding her father, who is suspected of murder. Nick, joined by his wife Nora, a wealthy heiress who loves fun, cocktails, and has a weakness for murder cases, moves effortlessly between high society drawing rooms and the city's seedy underbelly.

The dynamic between Nick and Nora is the true beating heart of the film, a surprisingly modern and gender-equal model for its time. Nora is not the classic "detective's wife" waiting in the wings, but an active, resourceful partner with her own peculiar moral compass, often bolder and more impulsive than Nick. Their relationship, made up of affectionate squabbles, continuous toasts (an implicit challenge to the recently ended Prohibition, which made their alcohol consumption a symbol of freedom and ostentatious well-being), and mutual admiration, becomes a fascinating subplot in itself. It is their relationship, rather than the mere detective enigma, that keeps the viewer glued to the screen, eager to witness the next spark between the two. Completing the family picture is the unforgettable terrier Asta, a true mascot and unwitting catalyst for comedic moments, demonstrating how even an apparently secondary element can contribute to the film's overall tone. Interrogating eccentric suspects like the inventor Gilbert Wynant, the mistress Julia Wolf, and the shady lawyer Herbert MacCaulay, and following intricate leads, Nick and Nora navigate elegant parties, refined dinners, and ample glasses of whiskey, uncovering a web of deceptions and secrets, until they discover the true culprit in a final plot twist that gathers all the protagonists in an ensemble scene, almost a theatrical skit.

An ironic and disorienting work that anticipates some aspects of film noir, such as the nocturnal urban setting, ambiguous and morally complex characters, and fatalistic atmospheres, but does so with a touch of lightness and irony that makes it unique in its genre. Unlike subsequent noirs, where fatalism and disillusionment were dominant, The Thin Man offers a vision of the criminal world that, though dangerous, is approached with a playful detachment, almost as if it were a giant board game. This lightness brings it closer to screwball comedy, of which Nick and Nora are perfect performers with their witty banter and explosive chemistry, placing them alongside iconic couples like Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby or Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in Adam's Rib. The film's ability to navigate the strict morals of the Hays Code, which was about to come into effect, is notable: Nick's alcoholism is shown with irony, never as a destructive vice, and allusions to extramarital affairs or the more sordid aspects of crime are skillfully concealed behind a veil of sophistication that made acceptable what would otherwise have been censored.

Furthermore, The Thin Man stands out for its innovative use of dialogue, brilliant and full of memorable lines, which contributes to creating an atmosphere of sophisticated irony and defining the characters with great efficacy. It's not just simple witty banter, but a true cryptic language that the two protagonists master with art, revealing the depth of their bond and their ability to read between the lines. It's a conversation that never stops, a continuous flow that reflects their intelligence and their ability to enjoy life even amidst the chaos of an investigation. Nick and Nora, with their delightful squabbles and torrential dialectic, inspired other famous detective duos like Sam Spade and Brigid in John Huston's The Maltese Falcon (1942), or Marlowe and Vivian in Howard Hawks's The Big Sleep (1946), to name just two very famous titles. It is, however, crucial to note the difference in tone: while subsequent hardboiled couples often exhibited a more pronounced cynicism and a dangerous attraction, Nick and Nora embody an emotional solidity that acts as a bulwark against the chaos of the outside world.

The Thin Man thus left an important legacy in film noir, influencing the portrayal of the detective, as well as the setting and narrative tone. Its ability to blend genres, to infuse lightheartedness into a crime context, and to present complex and fascinating characters opened new avenues. Van Dyke's film, with its elegance, its humor, and its subtle intelligence, contributed to creating a new type of noir, more sophisticated and ironic, which had a great influence on subsequent cinema. Not only in the crime genre, but also in romantic comedy, where the idea of an equal and astute couple navigating life's (or crime's) difficulties has become a lasting archetype. It is a work that, almost a century later, retains its effervescent charm, reminding us that even the darkest mysteries can be unraveled with a smile and a good glass of gin.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...