Raging Bull

1980

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Jake La Motta and his sporting and biographical trajectory. But Raging Bull, in the Scorsesean epic, is far more than a mere filmed biography; it is an uncompromising descent into the depths of self-destruction, a lyrical work on the primordial bestiality lurking within man and on the tormented search – or its painful absence – for redemption. Scorsese, a filmmaker of deep Catholic sensibility and inner torment, was so fascinated by reading La Motta's biography that he perceived in it the echo of his own demons, his own obsessions with violent masculinity and guilt, and decided to make a film of it, involving his trusted Paul Schrader, already a collaborator with the director on Taxi Driver, to write the screenplay. Schrader's imprint here is unmistakable: the portrayal of the isolated individual, the Alpha male incapable of communicating except through violence, and the almost biblical desire for self-punishment that manifests through physical and moral annihilation, a recurring theme in his canon of dispossessed and self-destructive characters.

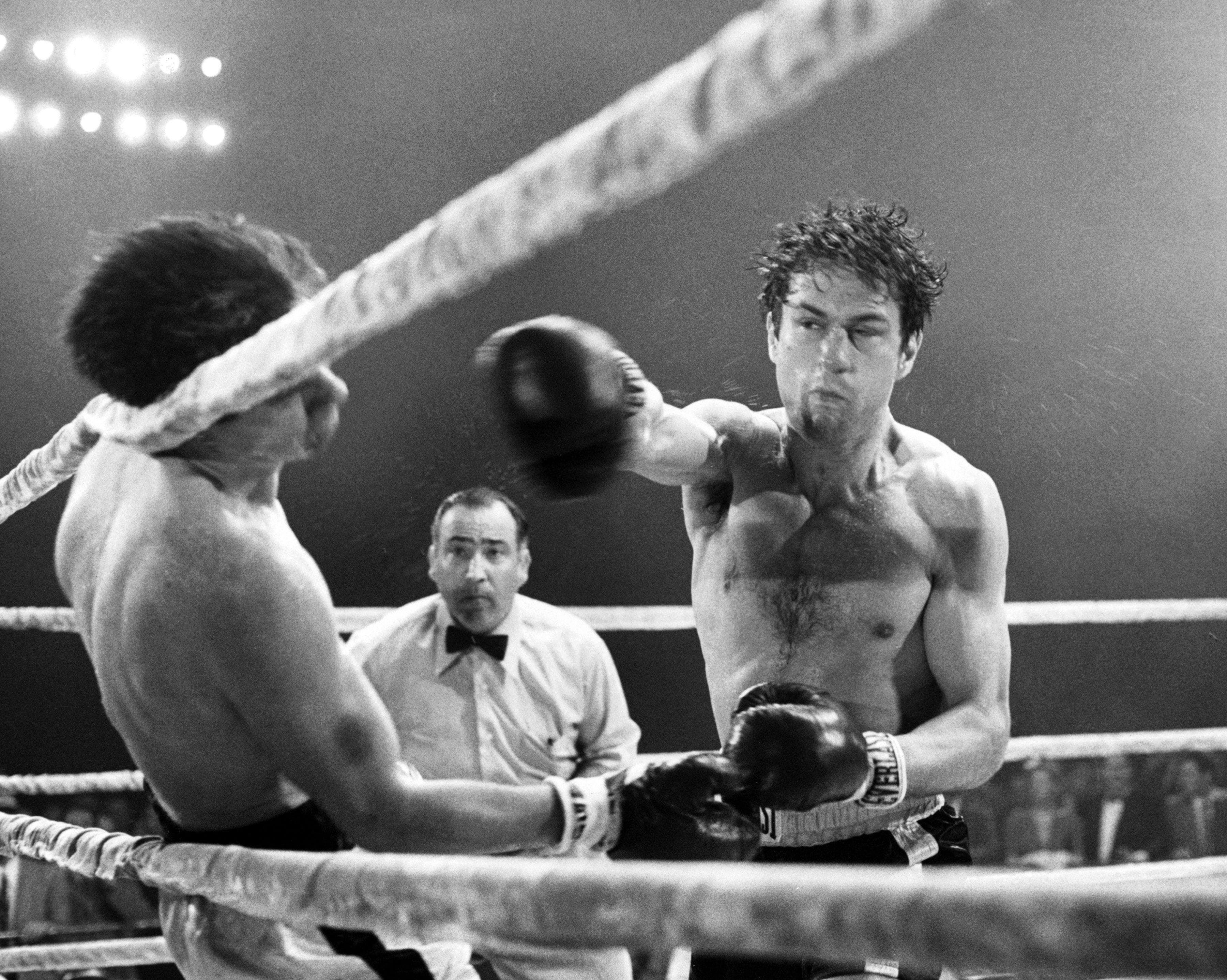

The events of the champion's life are paradigmatic of how personal affairs can be reflected in an athlete's sporting career, reverberating in the ring all the contradictions of a man who knew no limits, not even in his dearest affections. La Motta's violence is not merely physical, a brute force unleashed in a macabre and controlled dance between the ropes; it is an existential pathology, a blind rage that contaminates every relationship, every glimmer of domestic peace. The paranoid jealousy towards his wife, the irascibility that explodes in fits of uncontrollable fury, the savage violence even against his own family – epitomes of an obsession that devours him from within – are some of the distinctive traits of a man whose fury is relentlessly turned against himself. He is the matador who impales himself, the embodiment of a tragic archetype whose hubris inevitably leads to his downfall. Thus, the moment he was beaten by Sugar Ray Robinson in the ring, he lost everything: world title, marriage, home, fortune. This defeat is not a simple sporting setback; it is the culmination of a personal via crucis, the cathartic (or, more likely, anti-cathartic) moment when the man is forced to confront his own emptiness, his own unbridled bestiality.

His sad decline, which saw him lose every glimmer of greatness and dignity, slipping into a sordid existence as a nightclub manager and entertainer for a pittance, was somewhat mitigated by his performances in Italian-American nightclubs that called upon him to entertain the public. These scenes, far from offering true redemption, reveal a kind of secular purge, a purgatory where the wounded lion is forced to perform for crumbs, telling jokes or recalling lost glory. The famous final sequence, with La Motta reciting "I coulda been a contender" from the film On the Waterfront, is not a casual quotation, nor a mere cinephilic homage; it is the lament of a wasted opportunity, the cry of a man who exchanged the ring of life for the prison of his own mind, an echo of the Elia Kazan-esque Marlon Brando, which here takes on the connotations of an epic failure of the American dream.

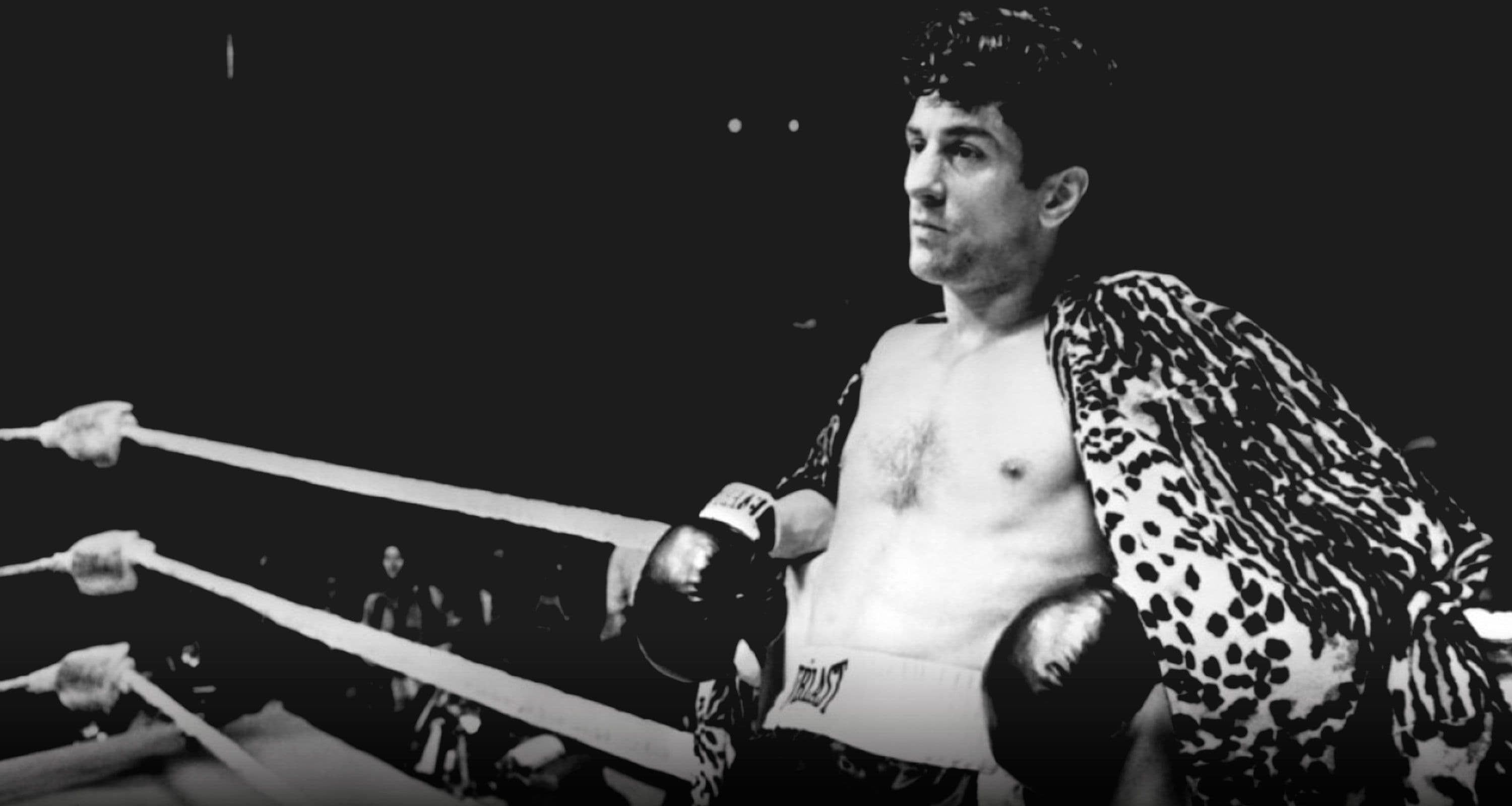

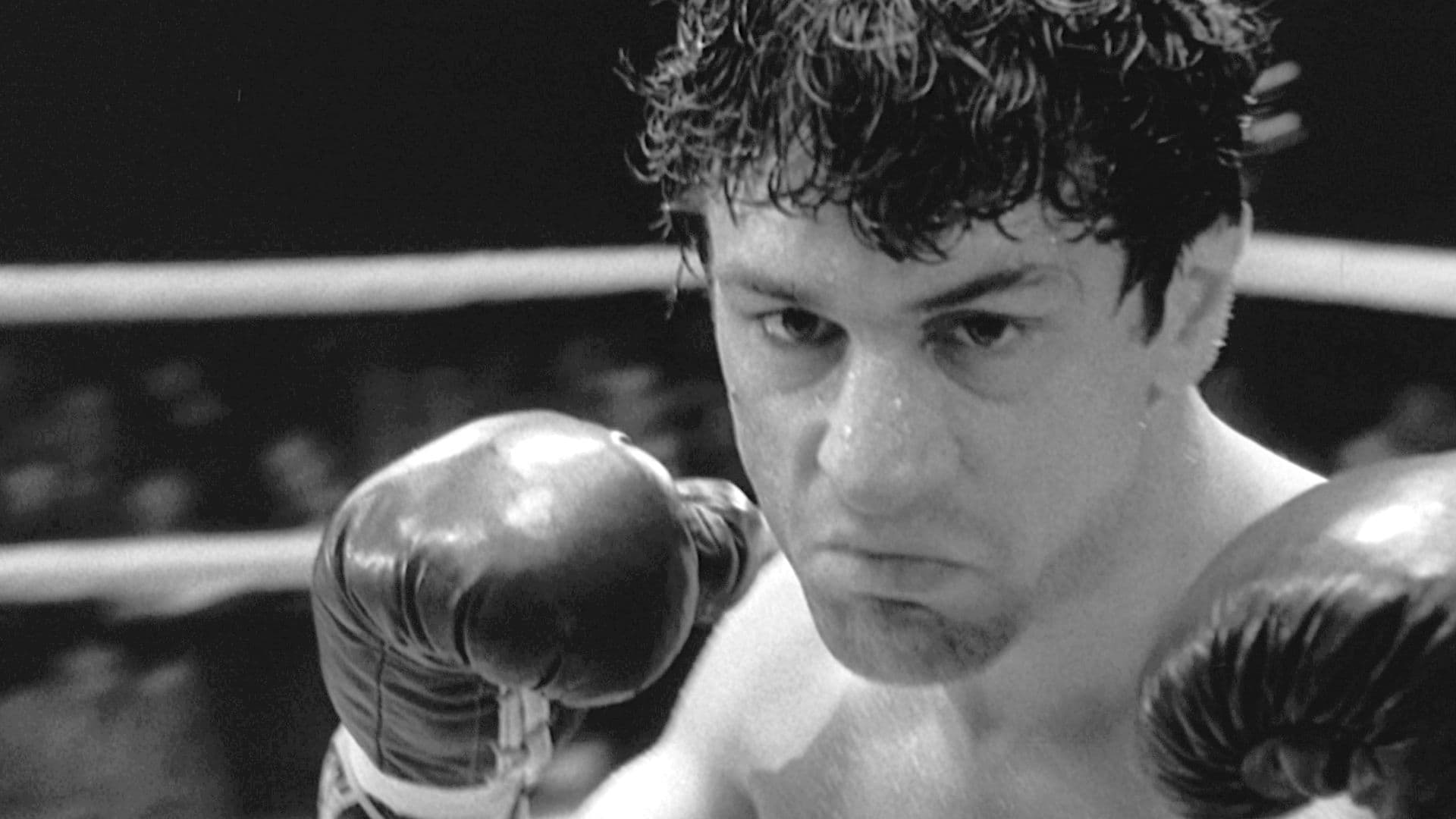

A sensational De Niro forges the character with maniacal professionalism, a true model for aspiring actors. His physical transformation – the agile and sculpted La Motta of his golden years contrasted with the flabby belly and panting breath of the boxer at the end of his career, a change achieved through disciplined gluttony that led him to gain over twenty kilos – is legendary, a feat that redefined the concept of "method acting," but it is his ability to bring out Jake's putrid yet pathetic soul that makes the performance immortal, a fusion of repulsion and tragic empathy.

Scorsese's direction completes the picture of this great film, transcending the sports narrative to paint a universal fresco of toxic masculinity, violence as a distorted language, and the impossibility of escaping one's fate. His staging is always attentive to every emotional surge and always precise in delivering a story that is as compelling and faithful to the narrative as possible. But this adherence is not mere reproduction; it is a stylistic re-elaboration that elevates chronicle to myth, an almost documentary immersion into the brutality of boxing and the protagonist's inner hell. The choice of black and white, in an era when color was the norm, is by no means an aesthetic whim, but rather an act of profound artistic coherence. It lends the film a timeless aura, almost like a journalistic chronicle from another era, and simultaneously intensifies the inner drama, making the blood on the canvas almost tangible in its visceral contrast, and the dingy patina of the nightclubs even more suffocating. It is a Goya painting in motion, where darkness and light clash to reveal human miseries, amplifying violence and solitude. Michael Chapman's cinematography is a masterpiece of expressionism, capable of transforming every bead of sweat, every bruise, into a sculptural detail, and every ring into a tragic arena, a stage for a restless existence. Raging Bull is not just a film about boxing, but a work of art about the human condition, about the animality that dwells within us and the extreme consequences of not knowing how to tame it, a visceral and unforgettable warning that has carved its place in the pantheon of world cinema.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...