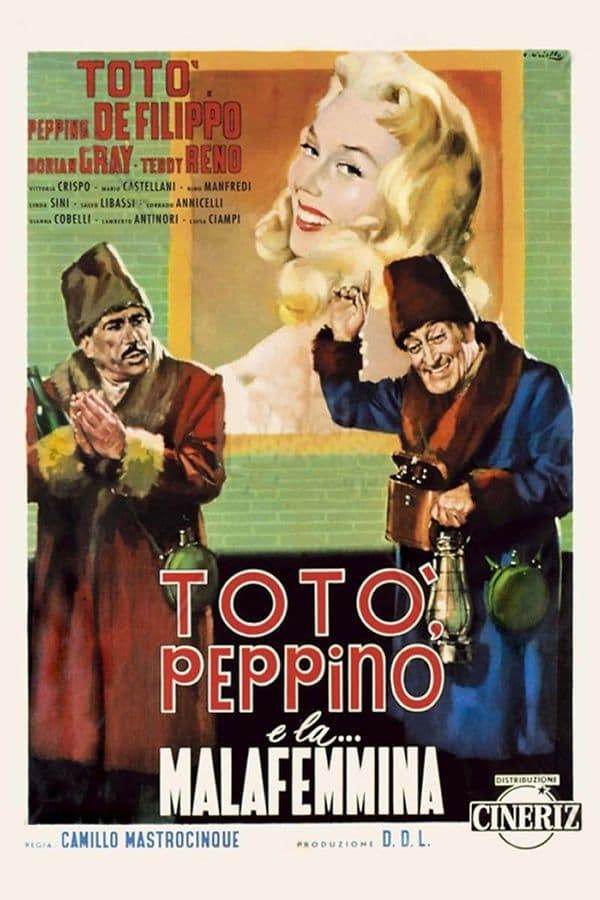

Toto, Peppino, and the Hussy

1956

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Camillo Mastrocinque, often underestimated among the giants of commedia all'italiana such as Risi, Monicelli, or Scola, was in reality a pioneer, a silent architect of that genre which would define an entire cinematic era. His direction, here at the service of the splendid duo formed by Totò and Peppino De Filippo, does not merely weave a "demented, ironic, and sarcastic" plot, but orchestrates a symphony of misunderstandings and cultural maladaptations with almost mathematical precision. Totò, the Prince of Laughter, and Peppino, his ideal foil, are not just simple actors here, but living archetypes of an Italy in transition, capable of translating the absurdity of everyday life into a universal humor, yet deeply rooted in the Neapolitan genius loci. Their understanding, made of glances, pauses, and sudden accelerations, transcends the screenplay, elevating every gag to a pure moment of comic grace, a mute yet deafening dialogue between two worlds and two mentalities.

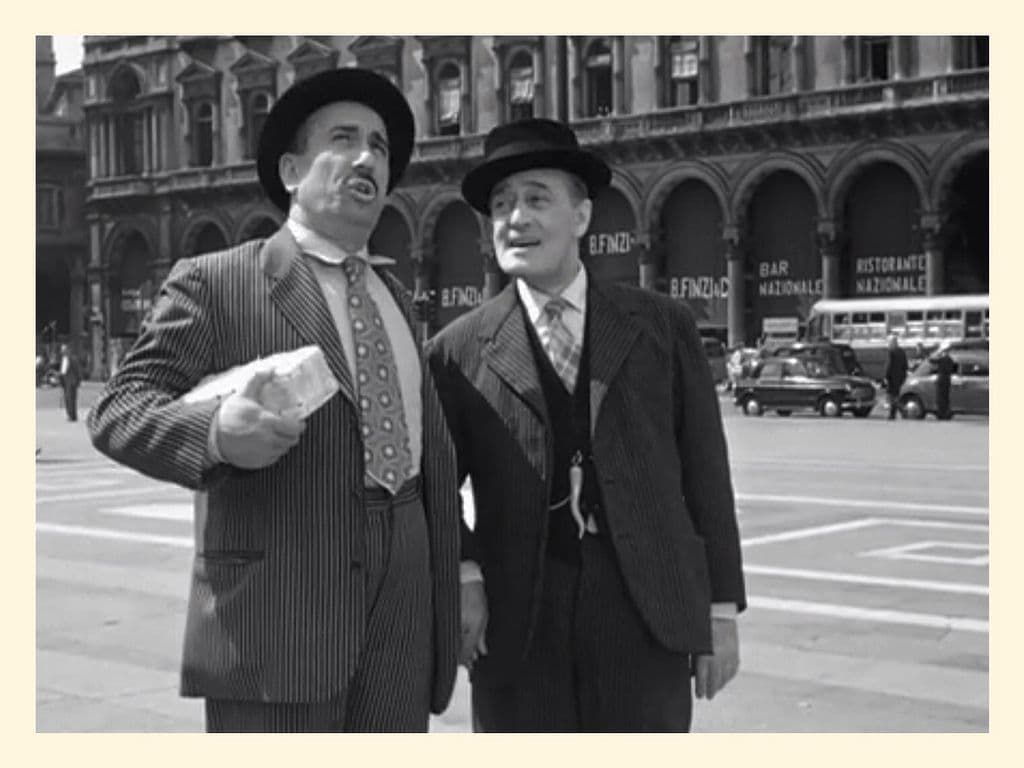

The story, in its almost fairytale simplicity, serves as a mere pretext to unleash the carousel of misunderstandings: the two uncles, Antonio La Quaglia and Peppino Caponi, depart from their small Southern world, a universe of customs and traditional values, with the redemptive mission to "redeem" their nephew Gianni, who dared to "lose his head" to the allure of a Milanese "malafemmina." But this journey to the "deep North," a metaphor for a rapidly evolving post-war and pre-economic boom Italy, proves to be an epic of disorientation.

Milan, with its still few but significant skyscrapers, its bourgeois frenzy, and its Cartesian logic, stands as an incomprehensible monolith in the eyes of the two provincials. It is not merely "alien and foreign"; it is a parallel universe, governed by social and linguistic codes that elude their comprehension, almost a ghost city of signs and signifiers erroneously decoded. The image of them, lost in traffic or in front of a modern restaurant, unable to order a simple meal, is the quintessence of the cultural clash that characterized the years of massive internal exodus. A contrast that in some ways recalls the anthropological approach of a Vittorio De Sica or a Pietro Germi in showing social rigidities, but here filtered through the distorted and liberating lens of laughter.

And it is precisely in this clash of worlds that, like a diamond set into the narrative fabric, the celebrated scene in which the two draft a letter to try and corrupt the woman who made their nephew lose his head, is inserted. It is not merely a gag, but a true anatomy of failed communication, an essay on the malleability and violence of language. Words, from tools of intelligibility, become weapons of semantic destruction, shattering any pretense of seriousness and logic. The choice to alternate between voi and lei (formal 'you'), the approximate declension of bureaucratic formulas, and the convoluted logic that leads to transforming an attempt at dissuasion into a surreal declaration of love or a veiled threat ("We highly desire to know: does Your Ladyship wish or not wish to leave our nephew?!"), are the stylistic hallmark of the entire sequence. The scene is so powerful that it has entered the collective imagination, cited and re-proposed in countless contexts, elevating Totò and Peppino not only to masters of comedy, but to veritable unconscious linguists, capable of dissecting the most recondite folds of popular and formal Italian. It is a moment of pure genius, demonstrating how the subtlest humor can emerge from the perfect mastery of linguistic imperfection.

It goes without saying that the Italian of the epistle is absolutely shaky, an understatement for saying it is a syntactic and grammatical edifice on the verge of collapse. But it is not simply incorrect Italian; it is creative Italian, a linguistic laboratory where dialect clashes with the pretense of an elevated register, all seasoned with conceptual errors and anarchic punctuation. It is the language of those who learned the rules by ear, applying them with a logic all their own, which disarms with its intrinsic, absurd consistency. The use of expressions like "vogliate gradire i nostri più sentiti ossequi" ("please accept our deepest respects") mixed with "siamo venuti con questa nostra... per dirvi" ("we have come with this ours... to tell you"), shows the collision between affected dignity and naive spontaneity. This linguistic anarchy is not a defect, but the very engine of the comedy, revealing the unbridgeable distance between intentions and their realization, between the pretense of authority and a genuine ignorance of forms. The scene, with Totò dictating and Peppino transcribing with the uncertain handwriting of a child, is a monument to communicative incapacity which, paradoxically, communicates more than a thousand speeches.

It should be noted how the comic verve infused into the screenplay, as often happens in Totò's films, presents relentless rhythms that are absolutely perfect in their synchronization with the narrative. Mastrocinque, with tight editing and shots that emphasize the protagonists' mimicry and gestures, manages to maintain high comic tension. Every line, every glance, every nervous tic of Totò finds its counterpoint in Peppino's exasperated yet always contained reaction. It is a comic ballet made of sudden accelerations and dramatic pauses, where silence is as eloquent as words. This dynamism is not accidental; it reflects the speed with which Italy was changing, an explosion of energies and contradictions that the two protagonists, with their apparent slowness and provincialism, manage to capture with brilliant immediacy. Their performance is not based solely on the script, but on the capacity for improvisation (or the illusion thereof), on the almost theatrical interaction that makes them one of the most unforgettable duos in Italian cinema, a veritable inexhaustible engine of laughter and reflection.

But the work is not just an ode to laughter; it also presents a not-so-subtle attempt to denounce social inequalities between North and South, and the latent racism that Southern Italians daily face in the North. In an era of massive internal migration, with millions of Southerners who left their lands to seek fortune in the factories of the industrial triangle, Mastrocinque's film stands as one of the first, and most astute, mirrors of this reality. Totò and Peppino, with their naivety and disorientation, become living symbols of an entire generation of migrants, viewed with suspicion, ridiculed for their accent or manners, treated with a condescension that poorly concealed deep prejudice. The film does not preach, nor does it emphasize drama, but through the deforming lens of comedy, it implacably stages the cultural, economic, and social gap. Their attempt to understand "modern" Northern habits – from the way they eat in restaurants, to interacting with bureaucracy or fashion – is a poignant satire on the rigidities and insularities of a society that struggled to accept its own internal heterogeneity. In this sense, "Totò, Peppino e la Malafemmina" anticipates themes that would be explored more openly by commedia all'italiana of the 1960s, confirming how laughter can be the most effective form of social denunciation.

A film that reconciles with a smile, but which obliquely, amidst a thousand laughs, also makes one think. It is the quintessence of Italian comedy in its noblest sense: an art capable of deeply entertaining while delving into human and social contradictions. The film is not only an timeless classic for the comedy of Totò and Peppino, but a valuable document of an Italy transforming at dizzying speed, divided between tradition and modernity, between regional identities and a nascent national consciousness. The "malafemmina" of the title, interpreted by a sensual Dorian Gray, is not just the object of desire or concern, but also the personification of a change in customs and morality that the two uncles, anchored to older values, can neither comprehend nor accept. The film, almost seventy years after its release, retains its comic power and social relevance intact, demonstrating that the most authentic laughter is that which stems from acute observation of reality, even its most uncomfortable aspects. A work that, without ever descending into the didactic, offers us an irreverent and profoundly human cross-section of an era and a country, confirming its status as a cornerstone in the pantheon of Italian cinema.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...