A Man Escaped

1956

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Perhaps one of the most beautiful prison films ever made, Robert Bresson's 1956 work enchants with its minimalism, its essentiality, its iconographic stripping down to the bare bones of meaning. A Man Escaped is not simply a film, it is the sum of its author's beliefs, a work that Bresson would not call “cinema” but, using his favorite term, “cinematography.” Bresson infuses this film with every drop of his cinematic philosophy, namely the disintegration of the cornerstones on which every film was built at the time: acting, editing, and soundtrack. For Bresson, cinema was filmed theater, an impure art contaminated by performance. His cinematography, on the other hand, was a new, pure art form that sought truth not in the actor's emphasis but in the relationship between images and sounds. Bresson pursued an anthropocentric cinema, where man is at the center of the scene and where every embellishment, every artifice must be reduced to the essential in order to maintain an obsessive focus on the character on stage. To achieve this, he did not use actors, but ‘models’, ordinary people forced to repeat gestures and words until they were emptied of all acting intention, until they became pure automatons. It is in this ‘automatism’, according to Bresson, that a deeper truth lies, an emotion that emerges involuntarily, almost by grace. Acting becomes the furthest thing from emphasis, with dialogues consisting almost entirely of monosyllables. The soundtrack, except for the heart-rending pauses of the Kyrie from Mozart's Mass in C minor, is entrusted with the role of subdued commentary on the images, nothing more than a whispered suggestion. The editing is nothing more than a didactic chronological scanning of the narrative. A powerful and realistic film that never fails to fascinate, as it establishes a solemn pact between director and viewer: the promise of Truth stripped of all fiction, as the opening caption states: “This story is true. I tell it without artifice.”

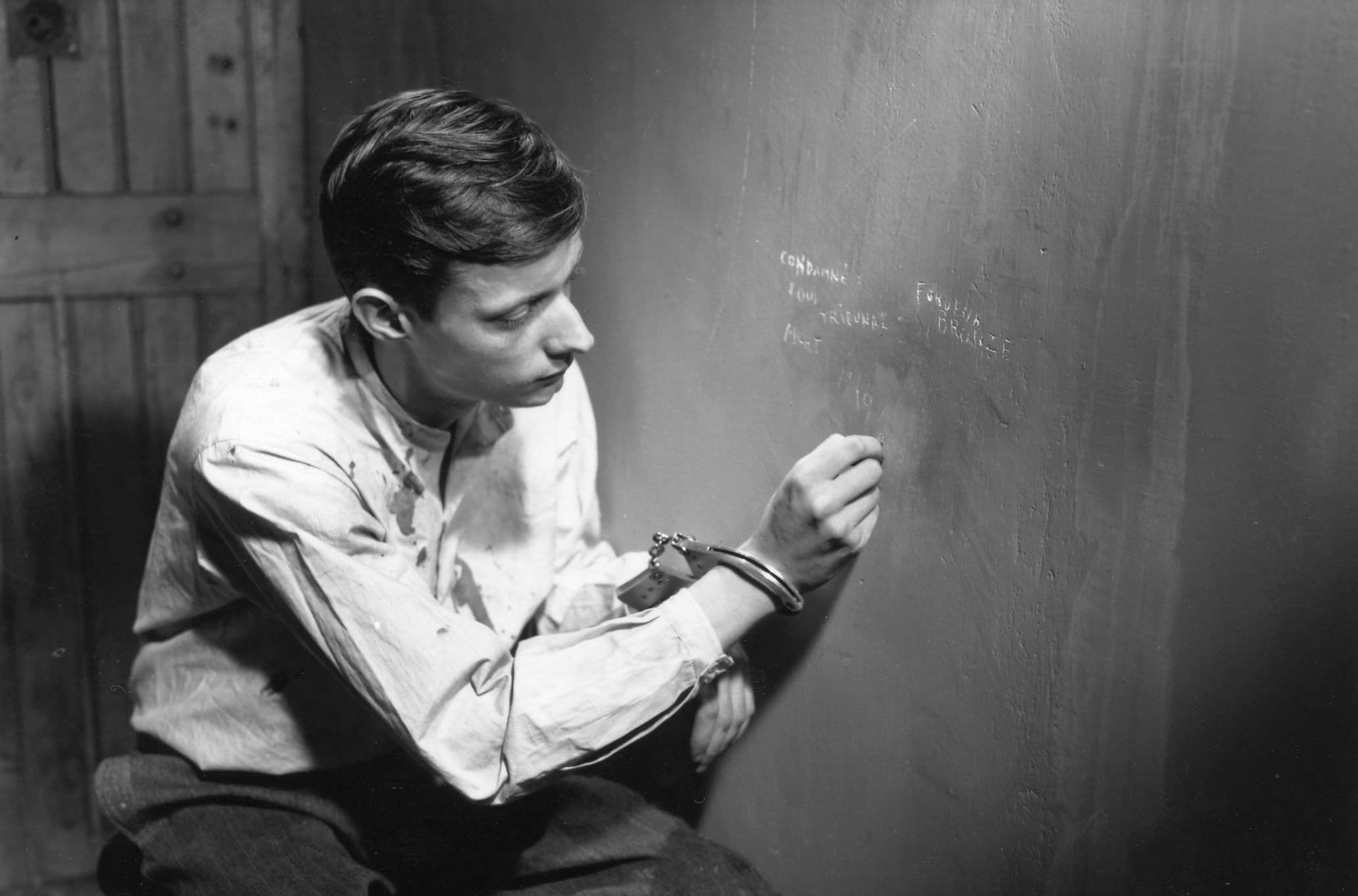

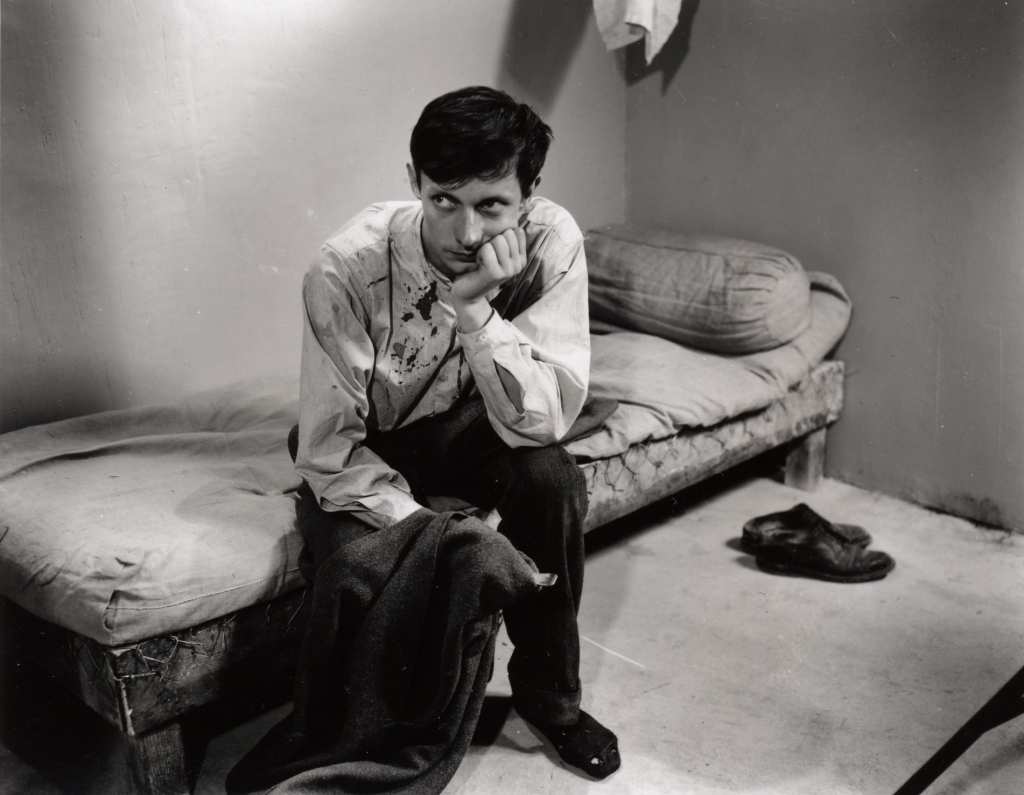

Based on an autobiographical account by André Devigny, a French resistance fighter who was captured and escaped from Montluc prison in Lyon, Un Condannato was triumphantly received by critics and won the award for best director at Cannes. Fontaine is a member of the French resistance who is captured after attempting an assassination. The man is taken to prison where, during interrogation, he is brutally beaten by the Gestapo before being locked up in a cell. The cramped space and sense of oppression weigh heavily on Fontaine, who nevertheless soon manages to shake off his despondency by thinking about how to escape from that place as soon as possible. What follows is not a simple chronicle of an escape, but a parable about faith and grace, imbued with an almost Jansenist rigor. The prison microcosm is made up of repeated gestures, whispers and gestures of understanding far from the gaze of the guards, of lives that intersect their destinies through the meat grinder of history. Fontaine befriends other inmates before seeing some of them brutally killed by the invader's summary justice. Realizing that the wooden door of his cell can be broken down, he works day after day, with the help of a sharpened spoon, to dig out the central panels to create an opening. He also makes ropes and hooks using makeshift materials he finds in his cell. Bresson dwells on this process with almost fetishistic precision. His hands, rather than his face, become the protagonists. It is tactile, sculptural cinema that celebrates human ingenuity and perseverance. When everything is ready for the escape, he is assigned a young cellmate, François Jost, apparently a deserter from the collaborationist French army. Fontaine, now close to execution, must decide as soon as possible whether to trust the boy, risking betrayal, or kill him to protect his goal of freedom.

A film that enters the imagination with the deadly precision of a sharp blade. The comparison with another masterpiece of the genre, Jacques Becker's Le Trou, is illuminating. If Becker's film is an epic tale of collective solidarity that ends in the tragedy of human betrayal, Bresson's is the story of a solitary and spiritual struggle. The success of Fontaine's escape does not seem to depend solely on his skill, but on an almost miraculous intervention, a form of divine grace. It is no coincidence that the full title of the film is A Man Escaped, or The Wind Blows Where It Wills. The latter part is a direct quote from the Gospel of John, alluding to the inscrutable nature of the Holy Spirit, and therefore of grace. Fontaine manages to escape not only because he is tenacious, but because the “wind” was on his side. The decision to trust Jost is not a strategic one, but an act of faith. Some scenes remain indelibly etched in the memory, such as the killing of the guard after climbing down from the first wall. Fontaine waits behind a shelter for the right moment to attack the German soldier, sharing his breath, the bored sound of his footsteps, and the smoke from his cigarette. Fugitive and Secondino merge into one another, and Bresson lingers with the camera on this suspension of time, as if every event were crystallized in that moment. Then Fontaine springs into action, and the camera remains fixed on the wall where he was hiding, while off-screen, with a sharp, terrible sound, he kills the guard. Only an eye as sensitive and brilliant as Bresson's could conceive such a beautiful and ferocious scene, where violence remains latent and never comes to light, but where two men from opposing factions are, for a brief moment, entwined in the silence of the night, both victims of the same death machine.

Bresson's greatness lies in his aesthetic of subtraction, an almost ascetic approach that brings him closer to a painter like Piet Mondrian than to a conventional director. Just as Mondrian reduced painting to straight lines and primary colors to achieve universal harmony, so Bresson strips cinema of all trappings to arrive at a spiritual essence. The ending is disarmingly simple. Fontaine and Jost walk through the fog of an almost ghostly Lyon, finally free. There is no triumphant climax, only the sound of their footsteps and Fontaine's voiceover uttering a sentence of almost shocking normality: “If my mother could see me...” After an hour and a half of metaphysical tension, the film ends with the most human and earthly of thoughts. It is in this fusion of transcendental rigor and the simplicity of human detail that the miracle of this film lies, a work that is both a breathtaking thriller and a profound meditation on freedom, faith, and grace.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...