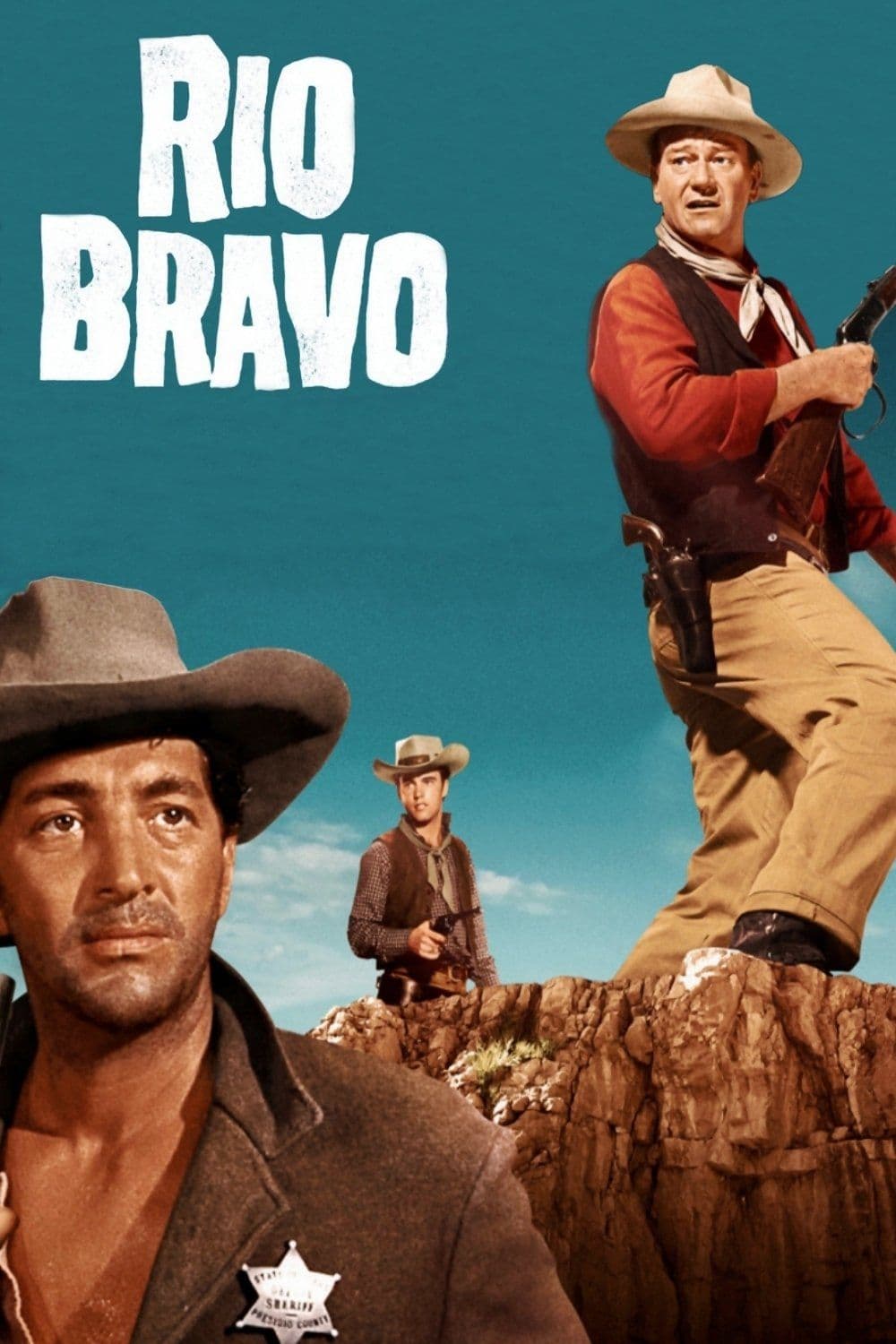

Rio Bravo

1959

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

For some (like Quentin Tarantino), Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo is THE quintessential Western film: a masterpiece of cinematic theatricality in which the three Aristotelian unities give rise to a crescendo of intangible tension, of hostility shut out, of invisible enemies kept at bay by a handful of desperadoes. And it is precisely in its rigorous adherence to what we might call a "chamber theatricality" that the film finds its most unusual strength. The almost total observance of the unity of place – confining the action mainly to the sheriff's office and its immediate vicinity – and the unity of time, with the story unfolding over a few days of grueling waiting, is not a limitation, but a brilliant device. It amplifies the psychological claustrophobia, forcing the characters to confront not only the external threat, but above all their own internal vulnerabilities and interpersonal dynamics. Hawks, a master of subtraction, demonstrates that true action does not lie in the roar of gunfire, but in the subtle alchemy that binds and unravels a group under pressure, transforming the Western genre from an epic of landscape to a drama of the soul.

The plot, quite sparse in truth, recounts the arduous confrontation between Sheriff John T. Chance, aided by three motley assistants, and a band of gunmen determined to free a colleague from jail. But beneath this narrative simplicity lies a thematic architecture of rare complexity. The film stands, not by chance, as a monumental reply to Fred Zinnemann's more acclaimed and perhaps morally ambiguous High Noon. Where Gary Cooper, Sheriff Kane, begged for help from a cowardly and indifferent community, John T. Chance embodies Hawksian stoic professionalism: help is not sought, it is only accepted if offered, and one faces one's problems with competence and an inflexible code of honor. Here there is no room for the rhetoric of the solitary and suffering hero; rather, the strength of professional cohesion and male camaraderie emerges.

Set almost entirely in the sheriff's office, it strikes for the perfection of its dialogues, for the complex architecture of its pacing, for the unparalleled atmosphere of uneasy fatalism that hovers over the narrative. Every line, every pause, every exchange of glances contributes to weaving an invisible web of tension and mutual understanding. The screenplay, chiseled by Leigh Brackett and Jules Furthman, elevates everyday chatter into an art form, revealing personalities, motivations, and fears without ever resorting to didactic explanations. Consider the moving parable of Dude (Dean Martin), the former gunman reduced to alcoholism, whose struggle for redemption is the true beating heart of the film. His vulnerability and his obstinacy in wanting to regain his professional dignity, with Chance's discreet but firm help, offer a profound reflection on addiction, friendship, and the possibility of redemption, far removed from the clichés of Hollywood heroism.

Alongside them, the gruff and irascible Stumpy (a masterful Walter Brennan) provides the comic counterpoint and the voice of popular wisdom, while the young, taciturn, and lethal Colorado (Ricky Nelson, surprisingly effective in his aura of mystery) represents the new generation of professionals, capable and disillusioned. And then there's Feathers (Angie Dickinson), a female figure of rare independence and wit, who is not simply a love interest, but a destabilizing and humanizing force for the taciturn Chance, capable of penetrating his shell of reserve with intelligence and mischievous irony. Their verbal skirmishes are an essay in seduction based on acumen and intellectual parity, a subtle duel that adds layers of richness to the protagonist's psychology.

The atmosphere of uneasy fatalism, moreover, does not stem from continuous explosions or shootouts, but from the constant presence of danger just beyond the door, from the awareness that destiny hangs over each person and that waiting itself is a torture. It is a film that teaches the value of strategic immobility, of knowing how to wait, of managing collective anxiety with a mix of black humor, camaraderie, and lucid professionalism. Hawks orchestrates all of this with a fluidity and naturalness that few directors have ever matched, creating a peculiar rhythm in which the action is interrupted by moments of singing (the unforgettable musical sequence with Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson), jokes, and introspections, almost as if to underscore the normality that persists even under the gravest threat.

Rio Bravo is not only a cornerstone of modern action cinema, but also of the anti-hero figure tout court. John T. Chance is not the spotless and fearless hero; he is a lonely, tired, almost resigned man who performs his duty not for glory, but out of an innate sense of responsibility and ethical rigor. His is a form of everyday heroism, of silent resistance. This vision of the competent and reserved professional, who trusts in his craft and his few trusted companions, is the heart of Hawksian aesthetics and has left an indelible mark. Its influence is evident in subsequent works that emulate its siege structure in confined spaces, such as John Carpenter's cult film Assault on Precinct 13, whose debt to Rio Bravo is explicit and declared. A film that continues to resonate, not only for its formal perfection, but for its profound and honest exploration of the human condition in the face of adversity.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...