Young Frankenstein

1974

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Mel Brooks conjures up Young Frankenstein, this devastating and sardonic comedy where he weaves a parody of old horror films, and quite simply of cinema itself, with enviable lightness. An operation that goes far beyond mere divertissement to delve into an affectionate yet irreverent homage to the gothic canon of Universal Studios. Brooks doesn't just mock; he dissects the very DNA of the horror genre, demonstrating a profound knowledge and a visceral love for the material he sets out to manipulate with ingenious irreverence. Unlike many parodies that rely on superficial gags, Young Frankenstein operates on multiple levels: it is a masterclass in comedic timing, a meticulously reconstructed period piece, and, surprisingly, a keen commentary on the very act of cinematic creation.

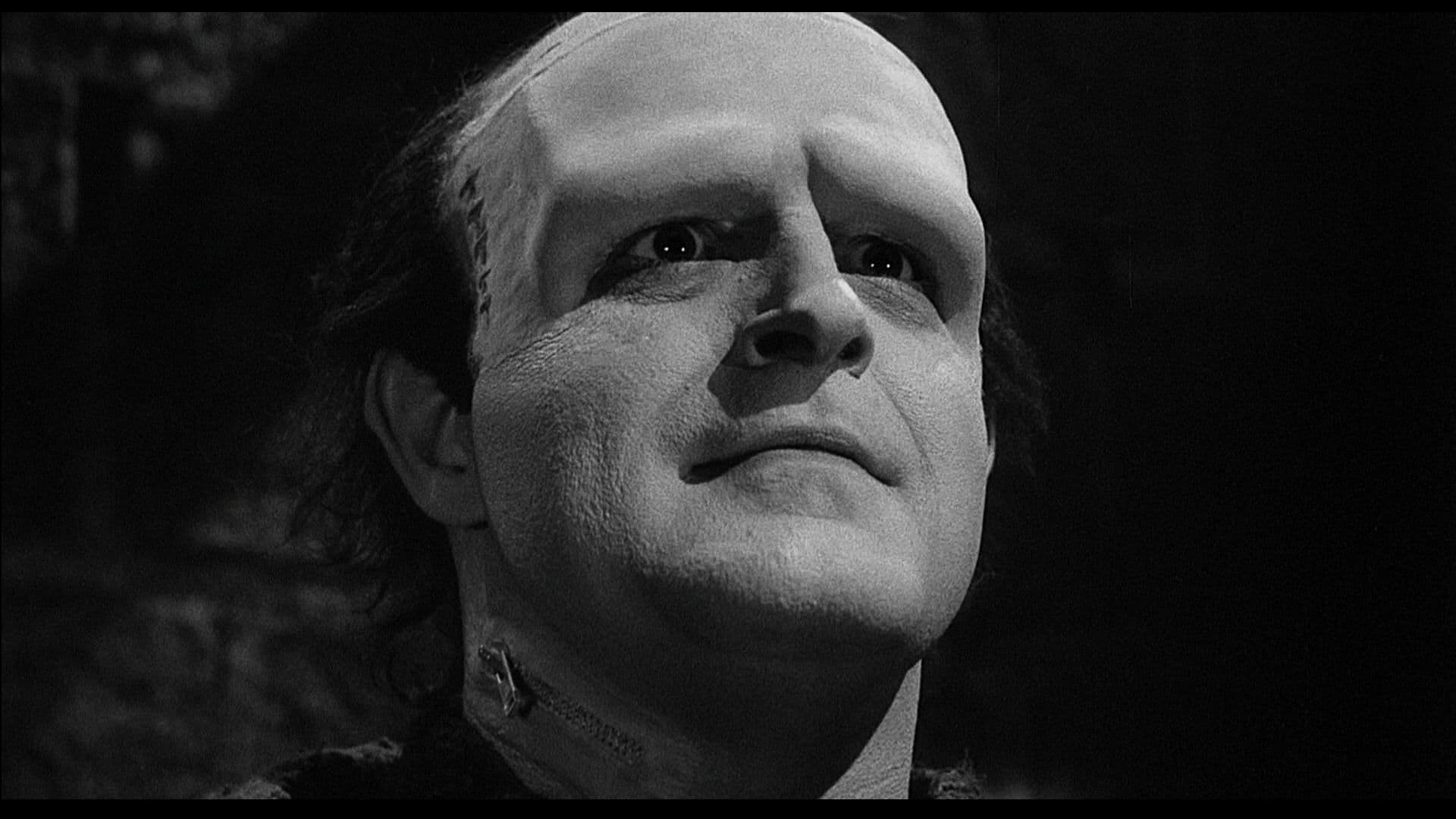

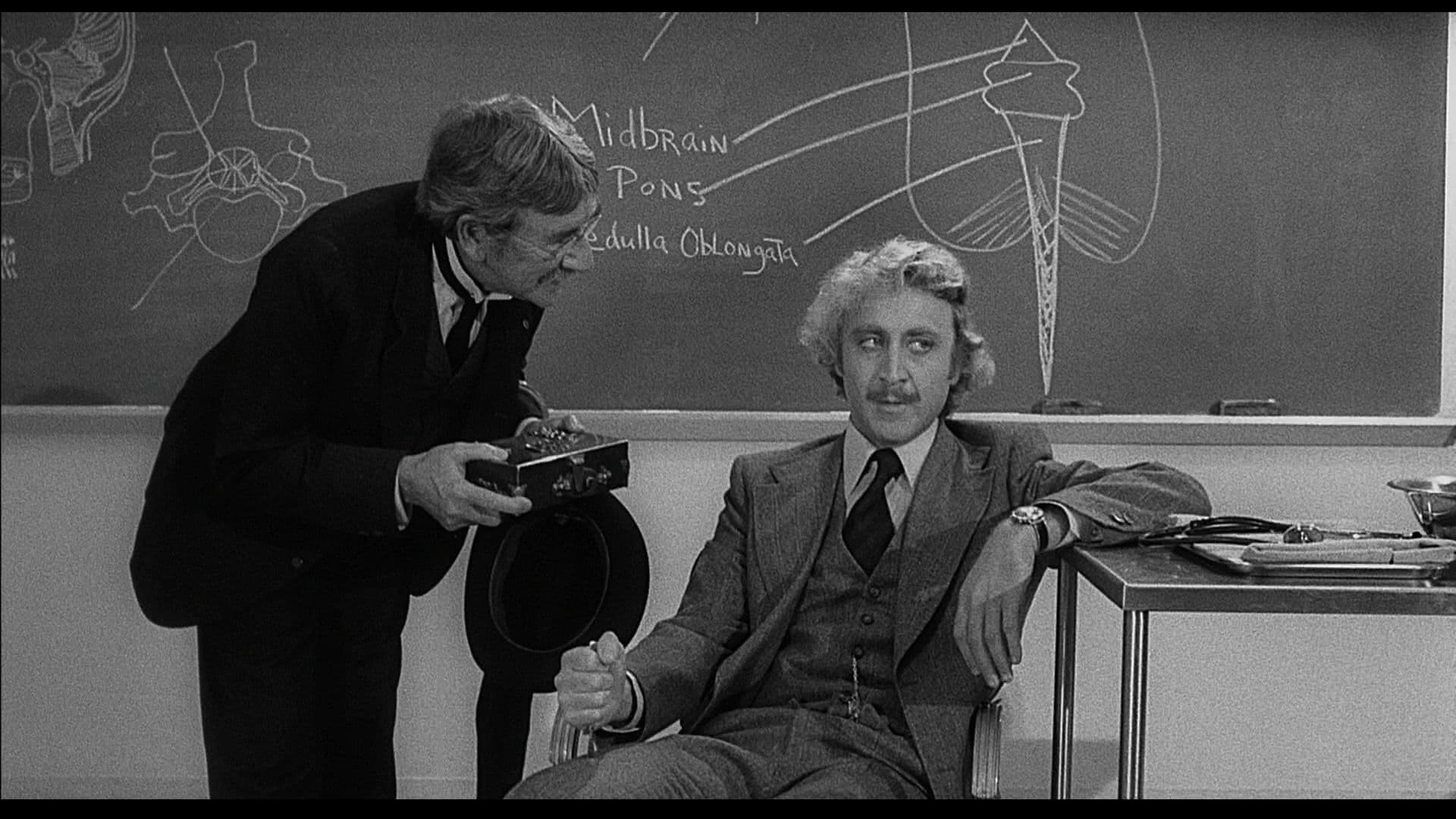

But it's not merely a comedic exercise, because this film features a subtle philological research into its settings, coupled with a directorial technique that enhances the artistic value of the work. The decision to shoot in glorious black and white, despite initial studio resistance, was by no means a mere nostalgic stylistic choice; it was an artistic imperative, a direct homage to James Whale's foundational Universal horror films. Cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld masterfully employed chiaroscuro lighting, echoing the dramatic shadows and expressive close-ups that defined the original aesthetic. Every set, from the flickering gas lamps of the laboratory to the menacing gothic castle, feels authentically plucked from the 1930s. This meticulous attention to detail, including the use of authentic laboratory equipment designed by Kenneth Strickfaden for the 1931 Frankenstein, elevates the film beyond simple comedy. It transforms it into a living, pulsating anachronism, a loving restoration that simultaneously mocks and celebrates its source material. It is precisely this deep immersion in the genre's formal vocabulary that makes the parody so devastatingly effective; one cannot subvert what one does not truly understand.

And yet, there's truly plenty to laugh out loud about in this film, shot in splendid black and white and featuring the late Gene Wilder and Marty Feldman, who formed a pair with proven comic flair (Wilder also participated in writing the screenplay with brilliant results). Wilder not only brings his Dr. Frederick Frankenstein to the screen with controlled hysteria and genius bordering on madness, but his imprint on the screenplay is evident in the depth of the dialogues and the comedic structure, often characterized by a crescendo of absurdity. Alongside him, Marty Feldman, with his bulging eyes and unparalleled comic timing, creates an iconic Igor, whose lightning-fast retorts and physical presence – consider the hump that magically "shifts" – are now etched into collective memory. But the ensemble triumph is ensured by an exceptional supporting cast: Cloris Leachman, memorable as the menacing Frau Blücher (whose name drives horses wild in a classic Brooksian gag), Teri Garr as the seductive and naive Inga, and Madeline Kahn, irresistible as the spoiled and hysterical Elizabeth, whose voice, modulated to shift from shrill highs to lascivious whispers, is a lesson in vocal comedy. Each of them is not just a sidekick, but a pillar supporting the edifice of comedy, demonstrating a synergy that goes beyond mere acting and borders on true theatrical alchemy.

The story takes Shelley's Frankenstein and revisits it in a comedic-satirical key: Dr. Frankenstein, grandson of the famous scientist, is an accomplished neurosurgeon living in the United States who disavows his grandfather's name and his reputation as a mad scientist. He is called back to the ancestral castle in Transylvania for an inheritance. Once he discovers his grandfather's former laboratory and finds the instruments with which his ancestor brought the creature to life, he lets himself be carried away by events and decides to complete his grandfather's experiment. With the help of a somewhat quirky assistant, he will bring the Frankenstein monster back to life, but with the wrong brain. Beneath the irresistible veneer of comedy, the film addresses profound and timeless themes with surprising acumen. The story of Dr. Frederick Frankenstein, who stubbornly disavows his grandfather's name only to succumb to the same irresistible creative madness, is a brilliant exploration of the genetics of genius (and madness). The thin line between scientific obsession and hubris is a common thread that links the parody to Shelley's original tragedy, raising questions about man's responsibility towards his creations. The Monster itself, far from being a mere caricature, becomes a vehicle to explore the nature of otherness and the need for acceptance. Its evolution from a primordial creature to a "gentleman" desperately trying to integrate into society is as moving as it is hilarious, transforming the horror cliché into a metaphor for marginalization and the search for identity. It is the eternal story of the "other" seeking a place in a world that doesn't understand him, rendered with unexpected sensitivity for a comedic film.

Dozens of memorable scenes: from Frau Blücher's name, capable of making horses bolt in a gag that has become a trademark, to Igor's choice of brain to insert into the hulking figure, which results in a hilarious dialogue between the professor and his assistant ("Uh, would you mind telling me whose brain I put in him? A.B. something! A.B. something"? Ab-normal, I'm almost sure that's the name..."), a sublime example of verbal comedy and surreal misunderstanding that plays on phonetic ambiguity and the Professor's desperation. The exclamation "It can be done!" shouted in front of the possibility of bringing the inert being back to life, is not only a famous quote but a cry of liberation from one's legacy, an acceptance of the madness that leads to creation. But the true gem, a moment of pure genius that indissolubly merges humor and pathos, is the "Puttin' on the Ritz" sequence. The Monster, in tails and top hat, performing a tap dance number alongside his creator, is not just a technical and interpretative virtuosity that breaks all genre conventions; it is the culmination of all the film's themes. It is the desperate attempt to ennoble the ignoble, to normalize the monstrous, to present to the world what has been rejected. Its tragic conclusion, with the audience terrified and the Monster wounded, amplifies the message about the difficult acceptance of the other and the creature's intrinsic solitude. And again, the bittersweet encounter with the blind hermit (a magnificent Gene Hackman), which turns out to be a compendium of unfortunate domestic accidents – including hot soup spilled in his lap and burning tobacco – is an ingenious subversion of the good Samaritan cliché, transforming the pathetic into the hilarious, and underscoring the absurdity of the human condition. Brooks doesn't just parody; he sublimates, elevates, and, in a sense, makes the legends he intends to mock even more eternal, solidifying his work not only as one of the greatest comedies of all time but also as a fascinating reflection on the nature of genius, monstrosity, and the ineluctable search for belonging.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...