Black Narcissus

1947

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Directors

A cardinal work for post-war Hollywood, because it had the merit of inaugurating a mystical speculative genre, beautifully ignored until then. The award-winning duo Powell – Pressburger once again demonstrates that cinema can and must make the viewer reflect, engaging and moving them. In a cinematic landscape still largely anchored to more conventional narratives, The Archers – as Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger liked to sign themselves – distinguished themselves by an aesthetic and thematic audacity that placed them on an almost metaphysical plane. Their vision was not limited to simple narration but aspired to explore the human soul in its most recondite folds, often through a revolutionary use of Technicolor, transformed from a mere tool of chromatic rendition into a vehicle for psychological and emotional expression. "Black Narcissus," in particular, emerges as a beacon in this quest, daring to delve into the depths of female spirituality and its intrinsic fragilities, a theme rarely explored with such acumen and visual intensity.

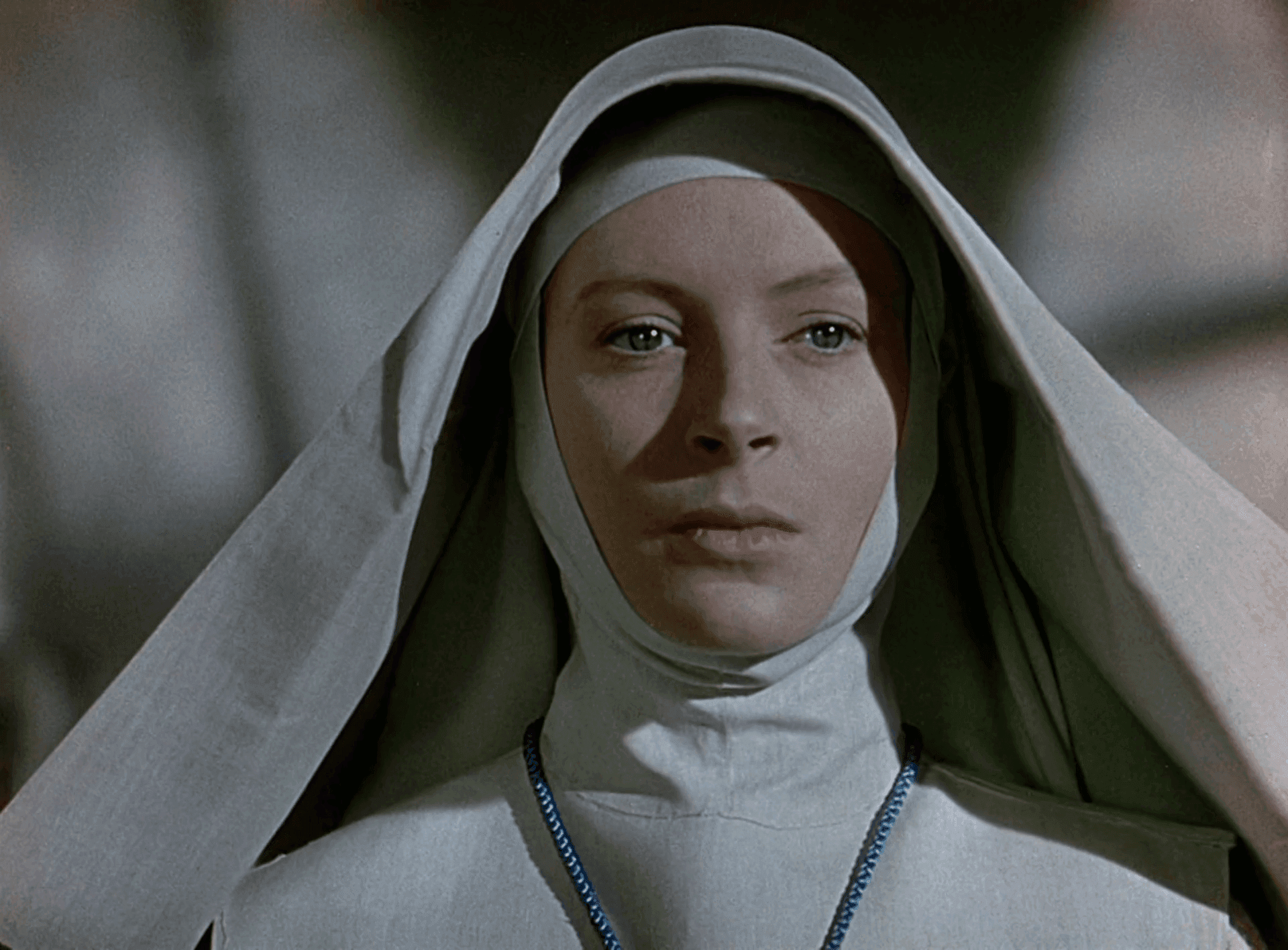

The story is that of a group of five nuns, stationed in Calcutta, who decide to establish a religious community in the rugged Himalayan region. Led by the young and determined Sister Clodagh, portrayed with sublime restraint by Deborah Kerr, the nuns embark on a mission that soon proves to be not only a geographical journey but above all an inner one, towards the abysses of the psyche. The dizzying isolation of the mountain, with its majestic peaks and menacing precipices, becomes a powerful symbol of alterity and the absolute, a place of sublime beauty that, however, conceals a perturbing power.

To do this, they settle in an ancient palace that was once a harem. This choice of location is by no means accidental, but a stroke of narrative and visual genius. Mopu, as this hermitage is called, is a fortress that still resonates with the sensuality and worldliness of its past. The walls adorned with erotic frescoes, the rooms warmed by the memory of dances and pleasures, the echo of a luxurious oblivion, starkly contrast with the austerity of the monastic cells and the nuns' rigid habits. It is the physical embodiment of all that monastic life aims to suppress: desire, vanity, passion. This friction between sacred and profane, between vocation and flesh, between spiritual and corporeal, becomes the true dramatic engine of the film.

Those atavistic walls will awaken dormant demons and ancestral doubts within them. The incessant wind that whips the Himalayan peaks and insinuates itself into the palace's crevices becomes almost a personification of these irrational forces, a constant sound that undermines serenity and discipline. Each nun faces her own personal crisis, but it is the psychological disintegration of Sister Ruth, splendidly portrayed by Kathleen Byron, that captures attention with an almost operatic ferocity. Her repressed jealousy, her creeping neurosis, and finally her manifest madness manifest in a chilling physical and psychological metamorphosis, transforming her from a devout servant of God into a diabolical figure, almost an evil doppelganger of Sister Clodagh. But even in Sister Clodagh, memories of a past love and the vanity of youth resurface with force, shaking the foundations of her faith and her role as a leader. The palace itself, with its glorious and sensual past, acts as a catalyst, an incubator for these primordial impulses that monastic discipline had only seemingly quelled. The "black narcissus" of the title alludes not only to an exotic and lethal beauty, but also to the narcissistic perversion that can arise from forced isolation and self-imposed repression, where the confrontation with one's deepest and unconfessable self becomes inevitable and destructive.

A truly splendid work in its frenzied pursuit of the more human side of religious mysticism and its gradual corruptibility. The film does not judge faith, but investigates its fragility when subjected to extreme pressures, when the external environment becomes a mirror of inner storms. It is a subtle and unsparing analysis of the repression of the senses and the dangers that derive from it, showing how human nature, with its impulses and weaknesses, is a karstic river that sooner or later re-emerges, sometimes with unprecedented violence. The collapse of order and discipline, both individually and communally, is represented with a dramatic crescendo that borders on psychological gothic, in some ways recalling the claustrophobic isolation and mental degeneration of works like Polanski's "Repulsion," albeit in a context of spiritual aspiration rather than pure pathology. British colonialism, while not the central theme, is a disturbing backdrop: the idea of imposing an alien faith and culture on such an intrinsically wild and ancient place proves to be a fatal presumption.

A film that slowly dispenses spiritual metaphors, transforming them into cold matter. It is here that the technical mastery of Powell and Pressburger, aided by Jack Cardiff's masterful cinematography, reaches its zenith. Every frame of "Black Narcissus" is a pictorial composition, a triumph of Technicolor used not for mere ostentation but to create a visual universe that reflects and amplifies the characters' state of mind. The intense reds of the local garments and blood-red sunsets clash with the glacial whites and blues of the monastic habits and mountain landscapes, creating a chromatic contrast that is itself an expression of the internal conflict. The bold choice to shoot almost entirely in the studio (Pinewood Studios), recreating the Himalayas with matte paintings of surprising realism and detailed set designs, lends the film a dreamlike, almost nightmarish atmosphere, which makes the psychological dimension of the story even more palpable. It is not reality that corrupts the nuns, but the projection of their own desires and fears onto an artificial and sublime backdrop. The shots, often oblique or from unusual angles, and the expressionistic use of light and shadow, transform the palace into a mental labyrinth, a stage for the tragedy that unfolds. The film thus becomes a visual allegory of the eternal struggle between soul and body, a work of art that, through its extraordinary visual physicality, probes the most extreme depths of the human condition, leaving an indelible mark on cinematic history.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...