I Vitelloni

1953

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

In his second film, Fellini unravels his wonderful language woven with adolescent memories, grotesque characters, picaresque exploits, and street irony. In this nascent phase of his filmography, the Rimini-born master does not merely replicate the poetics of neorealism from which he originated – as seen in Variety Lights – but inflects its conventions, turning them towards a more subjective and dreamlike exploration of the human soul. It is the seed of what someone would later label "pink neorealism," but which in reality is already pure Fellini: an immersion in a provincial universe where the fantastic and the everyday merge, where melancholy hides behind farce, and the desire for escape is palpable in every gesture. His figures, despite their detachment, evoke an ancient tradition of masks and types from Italian comedy, yet filtered through a gaze that is already premonitory of his future, grandiose human galleries.

A work that openly pays homage to his revered Rimini, reconstructed for cinematic purposes on the Tyrrhenian coast – a spatial and temporal artifice that testifies to the very essence of Fellini's cinema, which is never a mere reproduction of reality but its emotional and symbolic reinvention – something that, after initial bewilderment, was forgiven by his admiring fellow citizens. Rimini, for Fellini, is not just a city, but an archetype, a kind of lost Eden continually reconstructed by memory, a port from which one flees and to which one returns in myth. It is not the real Rimini, but "his" Rimini, that of childhood, dreams, and first disillusionments, an atmosphere he would rediscover, in more explicit and monumental forms, in the autobiographical masterpiece Amarcord. The choice to move the filming to Ostia, in an era when neorealism demanded fidelity to location, is already an act of audacious artistic independence, a sign of his intolerance towards dogmas and his early awareness that cinema is above all creation, not documentation.

The story narrates the exploits of five idle loafers – Fausto, Leopoldo, Moraldo, Alberto, and Riccardo – in a Rimini suspended in time and memory. They are not merely portraits of inactive youth, but an almost sociological investigation into a certain segment of post-war Italian masculinity, an existence suspended between the boredom of the provinces and the mirage of a future that never arrives. They are children of an Italy that, while moving towards an economic boom, left broad pockets of disorientation, a craving for escape without a defined destination. They embody the Peter Pan syndrome ante litteram, the fear of growing up and facing the responsibilities of adult life.

The five live on trivial jokes, mutual sarcasm, small expedients, trying to survive the fury of the day and trying not to stop and think about contingency. Their life is a daily commedia dell'arte, a succession of pranks, boasts, and small emotional deceptions that hide a deep void. They nullify themselves in the here and now, prisoners of an eternal Sunday, an existential limbo from which only one of them, Moraldo (played by Franco Interlenghi, Fellini's own alter ego), seems to find the strength to break away, in that final sequence which is one of the most poetic and melancholic in all of Italian cinema. Their inaction is not laziness, but a defense mechanism against the vertigo of the future, against the anguish of choice and responsibility. Every small prank, every insignificant flirtation, every nocturnal escape is a desperate attempt to fill the void, to delude themselves into living intensely, while real life flows by, indifferent to their immobility.

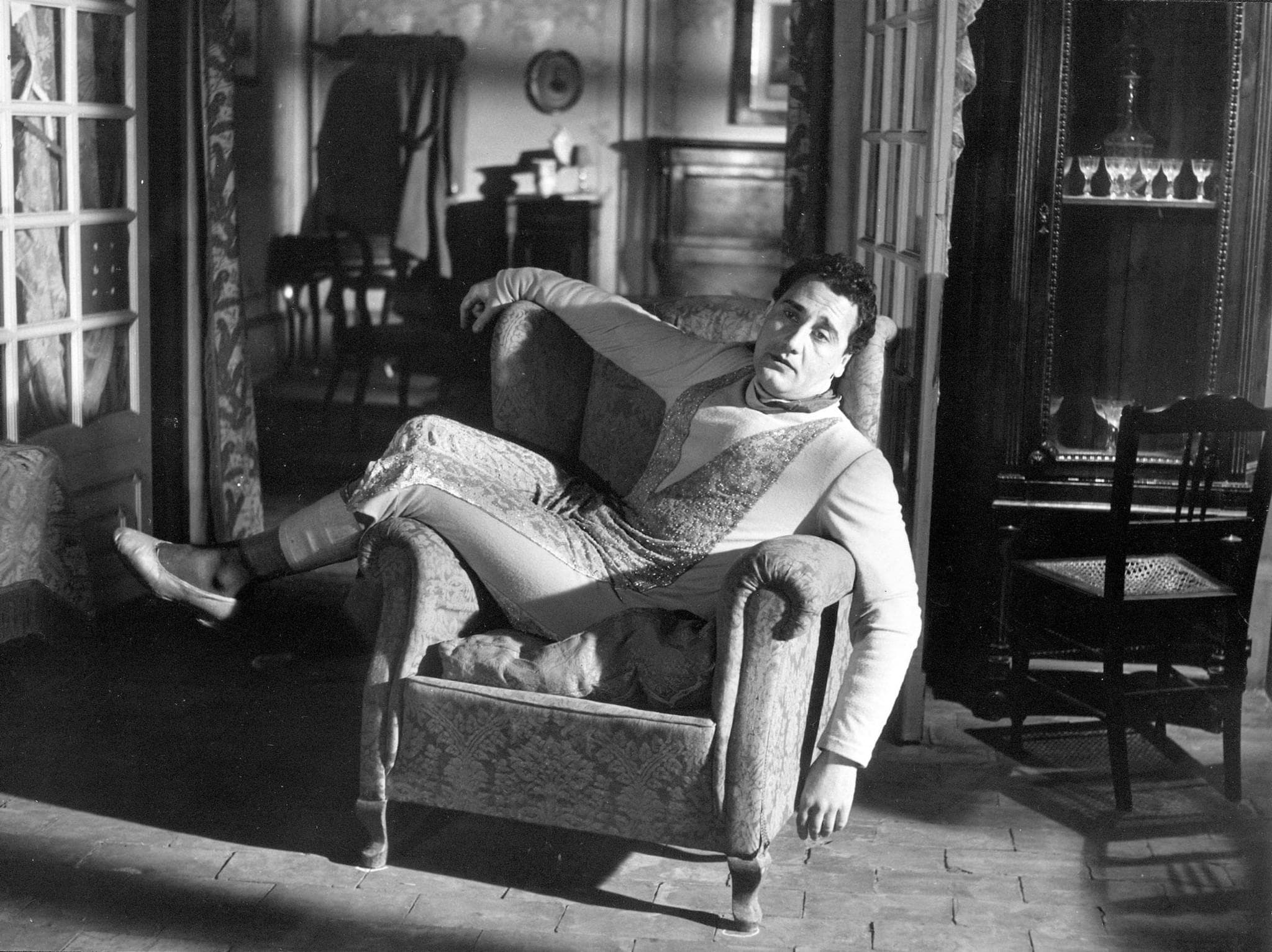

Among them, the contradictory character of Alberto (Alberto Sordi) stands out, offering glimpses of repressed violence alternated with grotesque boasts. Sordi's performance is a monument in itself, a crucible of bitter and pathetic comedy mixed with an almost tragic indolence. Alberto is the epiphenomenon of a certain Italianness, an irresistible mix of mammonism, opportunism, and an irresistible vainglory. His almost incestuous relationship with his sister, his irrational jealousy, and his outbursts of anger, followed by equally thunderous weeping, paint a portrait of immaturity and emotional dependence that is at once exhilarating and heartbreaking. Sordi, already a rising star, here consolidates his tragicomic persona, transforming Alberto into an unforgettable archetype, a man-child who rejects all forms of self-discipline and lives on emotional, even more than material, expedients.

A film that lays bare human weakness in the face of the gravity of reality. Not a loudly proclaimed socio-political reality, but the intimate and personal one of broken relationships, frustrated ambitions, the fear of failure, and the confrontation with adulthood. The "vitelloni" are lost creatures, whose dreams of glory – an acting career, literary success, a social life – mercilessly clash with their inability to act, their moral laziness. It is the portrait of an Italy that has yet to find its way, a metaphor for a generation that, despite living in an era of ferment and hope, finds itself navigating by sight, without an inner compass.

The lightness of the irony mellows and finally evaporates as the first problems arise. The smile turns into a grimace, the laughter fades into a sigh. The lightness, an initial stylistic hallmark, soon reveals itself as a mask for a deep melancholy. The consequences of their actions – an unexpected pregnancy, a sister's escape, the awareness of artistic failure – burst into their bubble of blissful irresponsibility, forcing them, for an instant, to face the harsh truth. It is in these moments that the film reveals its depth, shifting from comedy to bitter existential reflection. The curtain of farce opens onto a stage of solitudes and regrets, anticipating that vein of spleen that would permeate Fellini's entire work, from La Dolce Vita to 8½.

And behind this dichotomy, between the carefree surface and the abyss below, we glimpse, as if through a watermark, Fellini's loving gaze, one that absolutely does not condemn, but caresses his vitelloni as a poet does his beloved verses. Fellini does not judge, but observes with an almost filial participation, recognizing in his characters a part of himself, his own anxieties and unexpressed desires. His is a compassionate tenderness, a deep empathy for human frailties, a distinctive trait that would make him an unparalleled "singer" of the Italian soul. I Vitelloni is not just a portrait of an era or a generation, but a universal investigation into the difficulty of growing up, the perverse allure of immobility, and the eternal struggle between the desire for freedom and the necessity of responsibility. A work that, decades later, continues to resonate with its poetic power, offering us a mirror not only of the past, but of the eternal challenges of existence. The term "vitellone" itself has entered common parlance, testifying to the cultural impact and archetypal depth of this work of art.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...