The Hole

1960

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Universally recognized as Jacques Becker's masterpiece, Le Trou is the last dazzling film by the French director before his untimely death at the age of 53. It is a testamentary work, a pure distillation of his poetics, reaching an almost unbearable level of rigor and intensity. Based on an autobiographical novel by José Giovanni and co-written by Giovanni and Becker, the film draws inspiration from the legendary figure of Roland Barbat, the French master of escape, whom Giovanni met in prison. Here, Becker makes his first brilliant meta-cinematic gesture: he entrusts Barbat himself, under the stage name Jean Keraudy, with the role of one of the protagonists and, above all, the narrator. The opening scene of the film, with Keraudy addressing the camera directly, and therefore us, to guarantee the absolute authenticity of the story we are about to see, is not a simple prologue. It is a pact of truth, an abolition of the boundary between fiction and testimony that immediately immerses us in a universe of almost physical realism.

Four inmates sharing the same cell in the Parisian prison of La Santé plan an escape. On the eve of the plan's implementation, a fifth inmate, Claude Gaspard, is transferred to their cell. After being informed of the escape plan, and after intense deliberation by the group, Claude Gaspard decides to join them. The young man was imprisoned after accidentally wounding his wife with a hunting rifle, who was jealous and furious because of her husband's affair with her sister. His middle-class background immediately makes him an outsider in a group of hardened criminals, and Becker builds a subtext of mistrust and fragile solidarity on this social tension. After opening a passage in the floor, the prisoners gain access to the prison basement, through which they can reach the sewer tunnels. Through one of these underground tunnels, they find a point where, by digging a makeshift tunnel, they can reach the public sewer system and gain their freedom. Thus begins a long and exhausting excavation in which the prisoners take turns to complete the work, until the long-awaited demolition of the last wall separating them from freedom. But even stripped of all defenses, freedom is a capricious and elusive lady who will prove more difficult to achieve than expected.

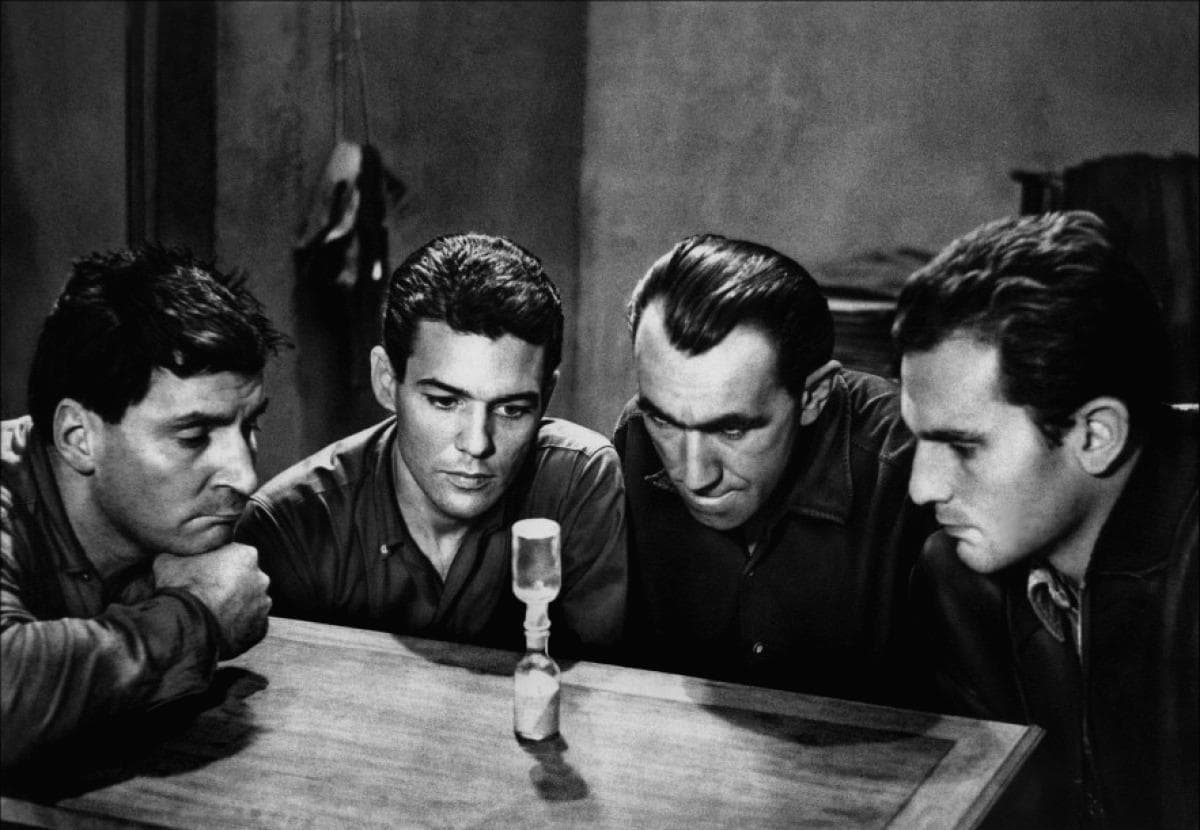

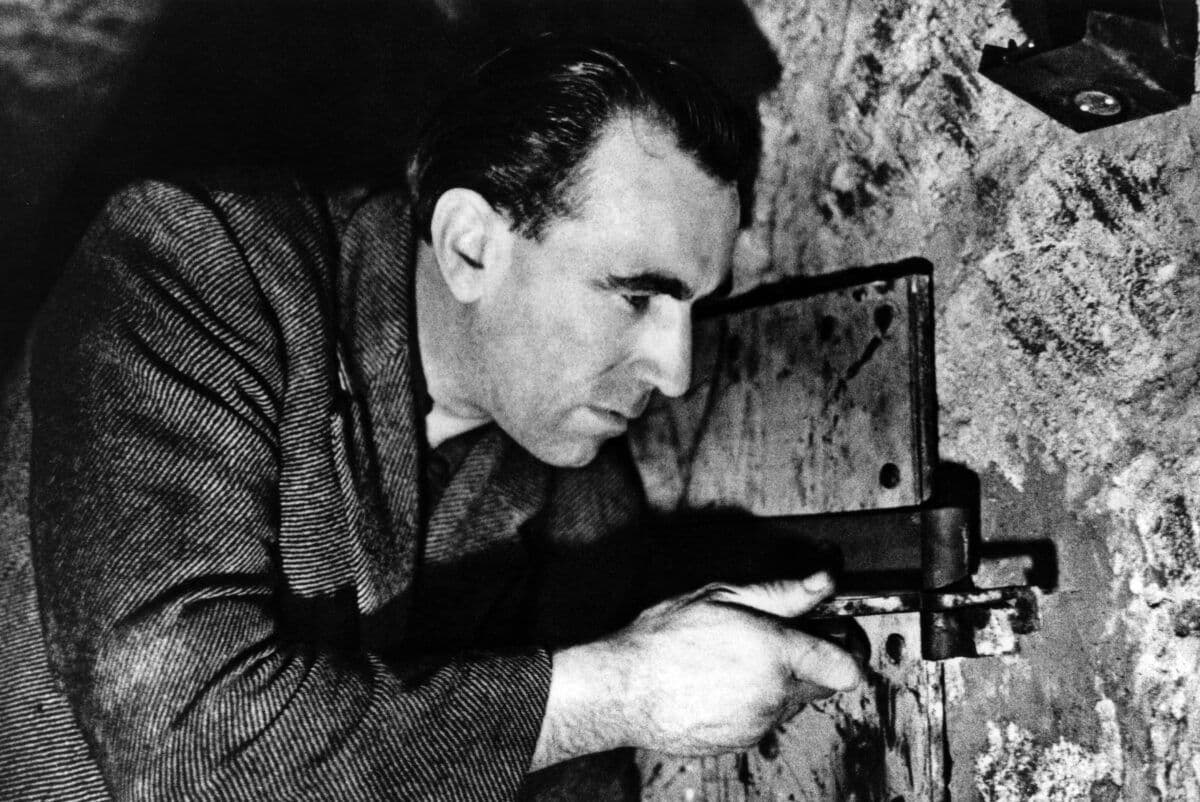

Becker infuses the film with all his artistry as a consummate craftsman of the camera. His is not a cinema of grand speeches or verbose psychologizing, but a cinema of gestures, glances, and matter. It is an aesthetic vision of the world born of a love for detail. The film is a symphony of manual labor. The long, almost silent sequences in which men take turns drilling concrete are not interludes in the action: they are the action itself. Becker makes us feel the fatigue, the sweat, the dust in our lungs, the deafening sound of metal on stone. It is the absolute pinnacle of process cinema, where the “how” becomes infinitely more compelling than the “what.” The velvety close-ups reveal the heart of the action to the audience by letting the little things speak: a crumpled cigarette packet, a match stuck in the hinge of a trapdoor, the makeshift handle of a hacksaw, an hourglass made from two medicine bottles, an ingenious mannequin constructed from cardboard boxes and moved by a string to deceive the guards, the debris and dust from the fugitives' excavation, a toothbrush with a fragment of mirror to spy on the guards' movements. All these objects, humble tools transformed by human ingenuity into instruments of liberation, form a wonderful mosaic that takes the shape of an ingenious and portentous narrative machine to which Becker entrusts his work.

In its almost ascetic rigor, the most fitting parallel is with another masterpiece of prison cinema, Robert Bresson's A Man Escaped. Both directors share the same faith in the power of detail, in the meticulous description of the process as a form of narration, and in the total absence of extradiegetic music so as not to contaminate the purity of reality. But there is a fundamental philosophical difference. Bresson's film is the chronicle of a solitary undertaking, an almost spiritual act of faith by one man against the system; his escape is a miracle. Il Buco, on the other hand, is an epic tale of the collective. Its strength and tragedy lie in the group dynamics, in the creation of a forced brotherhood based on mutual trust as the only fragile resource. Here, grace is not divine but human, and therefore infinitely more precarious. The viewer is captivated by this perfectly contextualized microcosm, whose every nook and cranny can be explored, feeling almost like the sixth man in the cell. The result is a film of striking beauty, the last precious legacy of a great director who knew how to lay bare man and his neurotic contradictions through a language that expanded from the bare image to the Concept, from the particular to universal iconography capable of imprinting itself on the imagination of those who watched his films.

The ending is one of the most bitter and devastating conclusions in the history of cinema. After days of inhuman fatigue, mortal danger, and almost moving solidarity, the dream of freedom is shattered not against a concrete wall, but against the far more insurmountable wall of betrayal. Gaspard, the bourgeois, the last to arrive, chooses his own individual interest, sacrificing the fate of the group. The last shot, a prolonged close-up of Roland/Keraudy looking at Gaspard through the peephole of his new cell, is an abyss of contempt and silent disillusionment that is worth a thousand words. That look encapsulates the entire tragedy of the film. The ‘hole’ of the title is not just the one dug in the prison floor. It is the hole in the pact of trust between men, the chasm that opens up when solidarity gives way to selfishness. This is why Il Buco is an absolute masterpiece: it is not just the chronicle of the greatest escape ever attempted, but a powerful parable about the difficulty of escaping from the most secure prison of all, that of our own nature.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...