The Cameraman

1928

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

In the late 1920s, a great artist revolutionized the use of bodily mime in silent cinema, transforming his own body into an incredible expressive vehicle where dynamism, movement, spatial awareness, and gestures contributed to the creation of an indispensable archetype of comedy, born from unparalleled talent. That man, of course, is Buster Keaton, and we all know and love his films, his irresistible gags, and also his flair for constructing characters with a few simple body movements. His famous nickname, "The Great Stone Face," was not just a mere affectation, but the keystone of his revolutionary comedy: his unalterable, almost mechanical expression served as a blank canvas onto which the chaos of the world was projected, amplifying the absurdity of situations and the intrinsic vulnerability of the common man. Where Chaplin expressed emotion with a trembling lip or Lloyd aspiration with a sly smile, Keaton entrusted to inexpressiveness the force of a hurricane, transforming imperturbability into a vehicle for laughter and, often, touching melancholy. His almost engineering precision in constructing gags, the result of an innate understanding of physics and movement, elevated physical comedy to an almost balletic art form, detached and sublime.

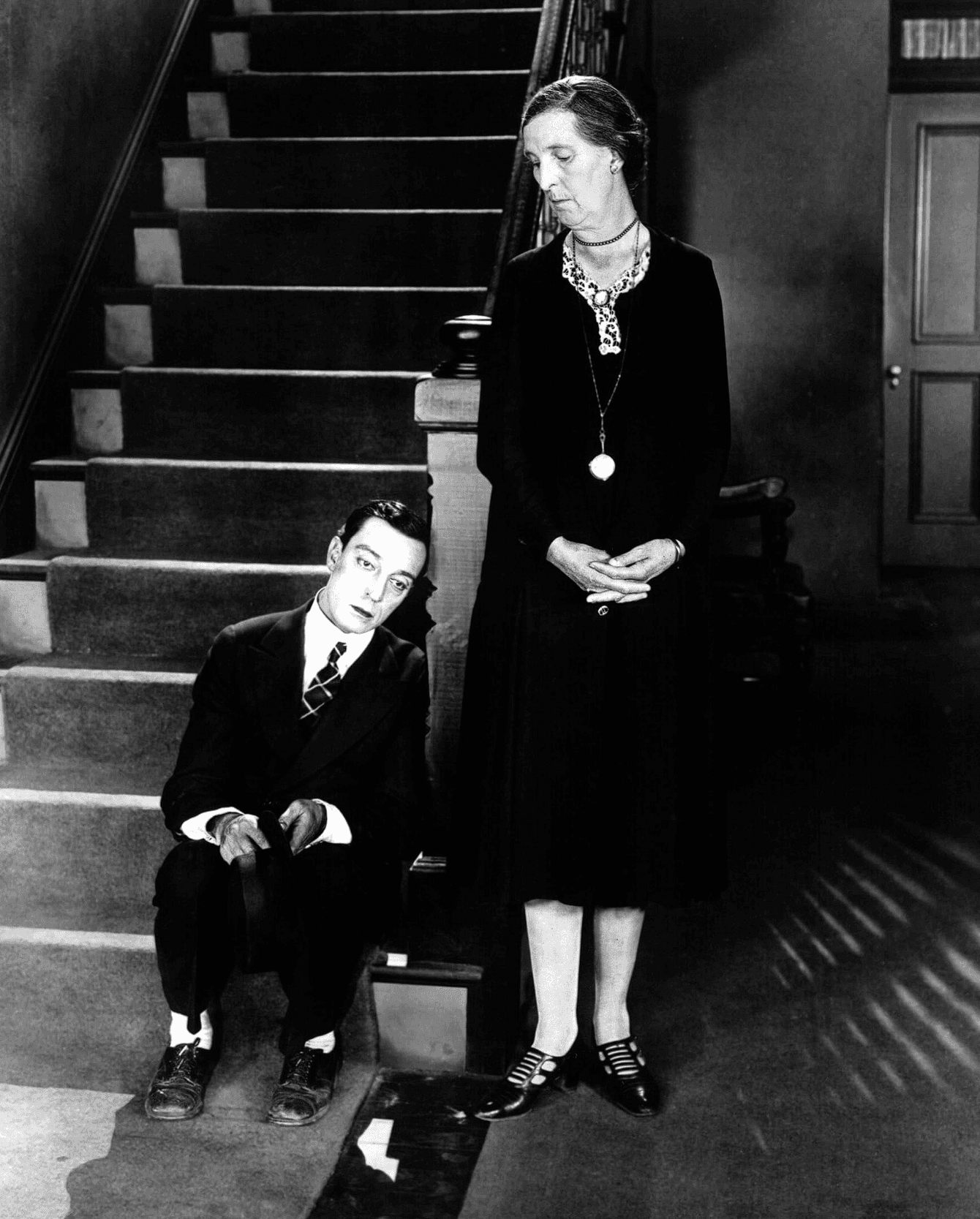

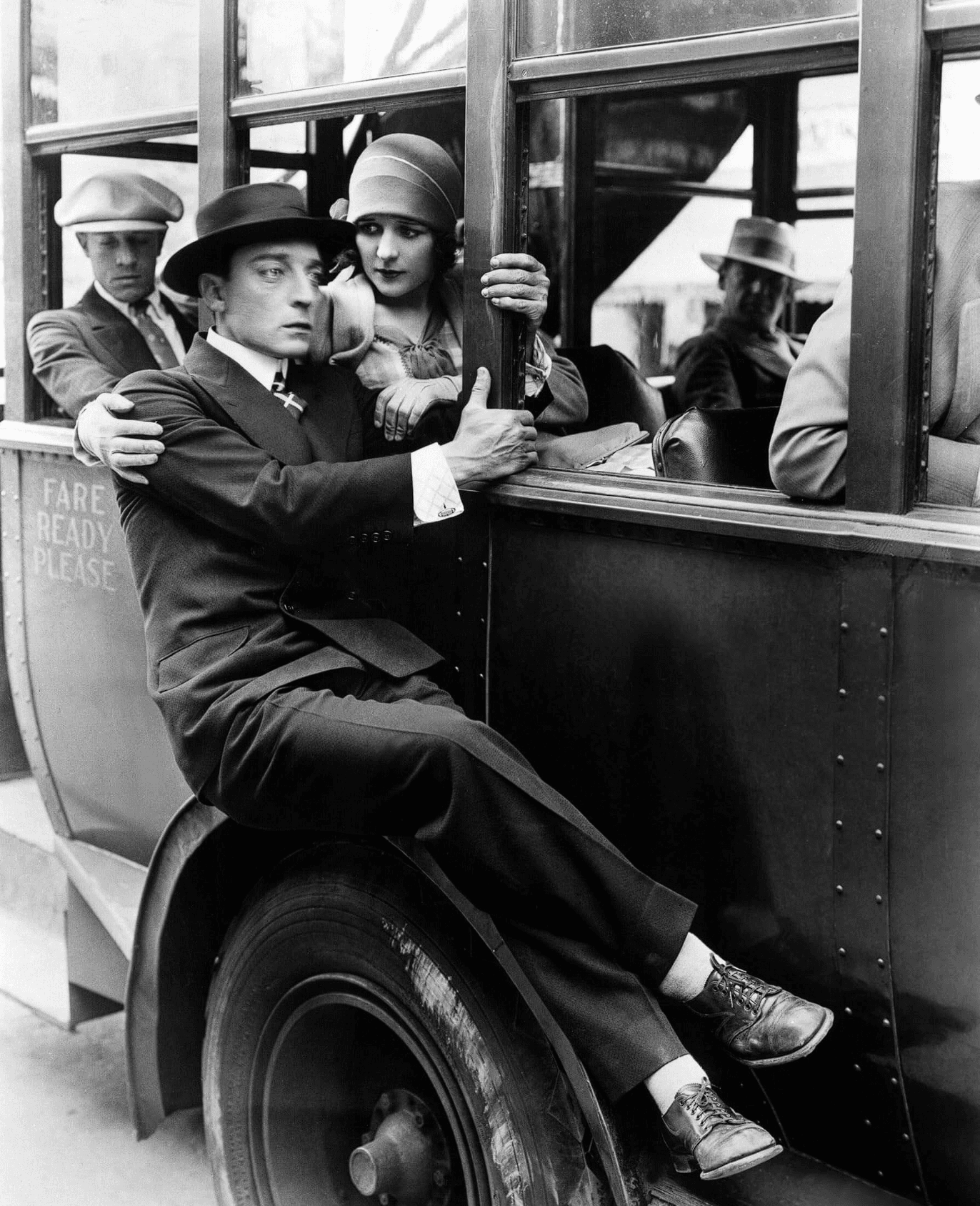

This work is no exception and marks Keaton's directorial debut (albeit uncredited) for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Keaton, with his inimitable facial expressions and extraordinary mastery of his body, transforms every situation into an irresistible gag. From acrobatic chases to interactions with the monkey Josephine, every scene is a small masterpiece of physical comedy and perfect timing. But The Cameraman is not just a succession of hilarious gags. Keaton, with great sensitivity, introduces elements of melancholy and poetry into the narrative, creating a fragile and tender character who evokes empathy and emotion in the audience. The Cameraman is the first film Keaton made for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer after leaving United Artists. This transition marked an important moment in his career, but also the beginning of a period of creative difficulties due to studio interference in his work. It was not just a change of studio, but a genuine clash between Keaton's auteur vision, accustomed to almost total control over his works, and the nascent Hollywood studio system of the major studios, which preferred standardization and constant producer intervention. The film itself, centered on the figure of an outsider trying to make his way in the film industry, takes on a surprising meta-narrative resonance, almost prophetic of the artistic battles Keaton would have to face in the years to come.

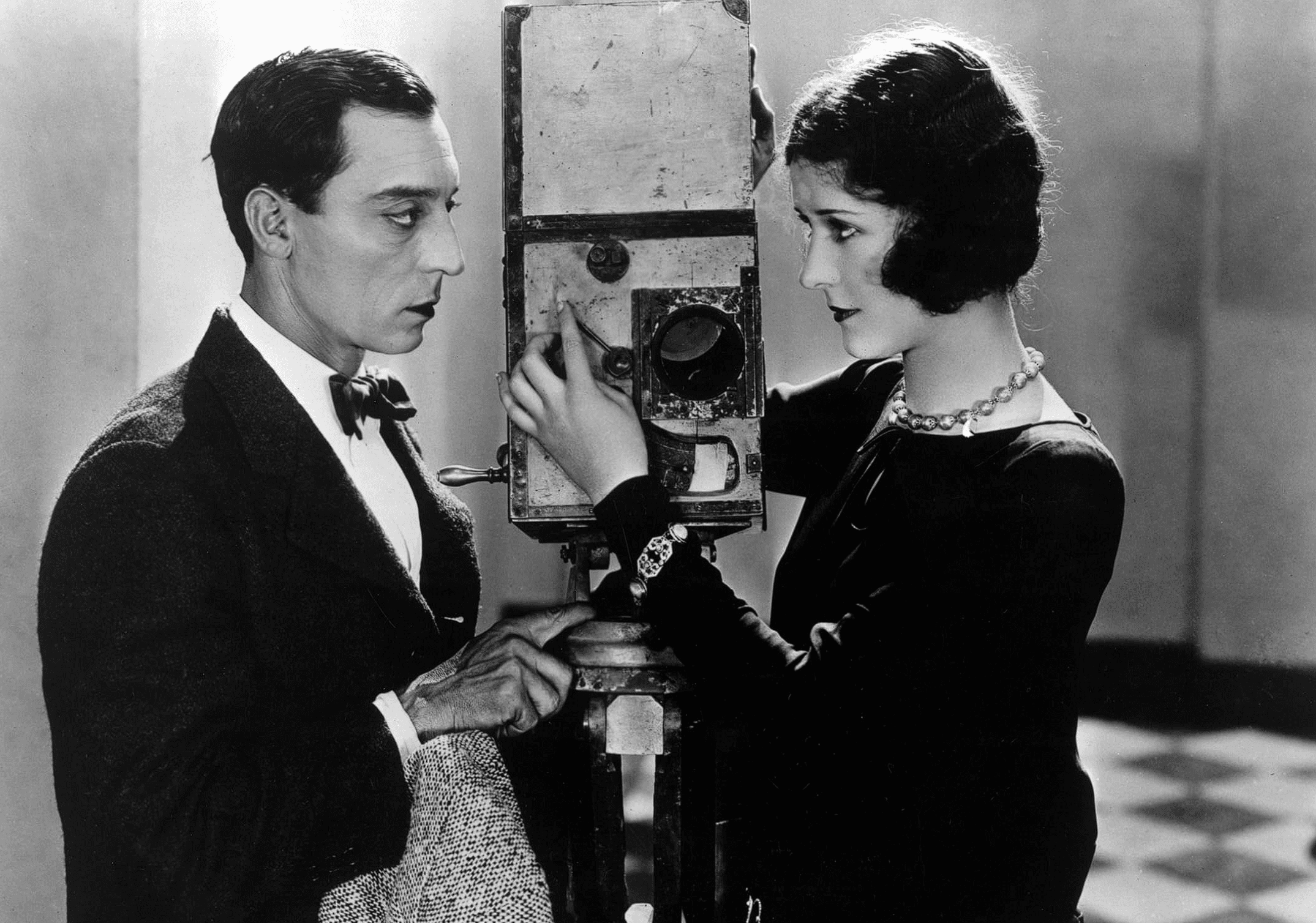

The story is that of a man who, having fallen in love with an MGM employee, does everything to enter the world of cinema by trading his typewriter for a camera. After a hilarious string of failures, the man will succeed with the help of a monkey. The camera, initially a cumbersome burden and cause of disastrous failures, gradually becomes a kind of extension of the protagonist, an eye through which to perceive and interact with the world. This exchange of tools from writing to filming is not coincidental: it is the transition from narrative aspiration to pure observation, a symbolic gesture that encapsulates his devotion to the film medium.

A brilliant work that demonstrates (if there were any need) how a great comedian needs only a few simple tricks to ignite his audience with smiles. His comedy, based on the universal language of the body and the observation of human behavior, transcends the barriers of time and cultures. Keaton, with his genius and humanity, created a work that celebrates the power of love, the tenacity in pursuing one's dreams, and the poetry hidden in everyday life. Keaton experiments with new cinematic techniques, using the camera in a creative and dynamic way. Examples include subjective shots that show the director's point of view, or scenes filmed with a handheld camera that lend the film a sense of immediacy and realism. In some scenes, the handheld camera is used to show Buster Keaton's point of view, as if he himself were filming the action, an innovative technique for the era that anticipated by decades the aesthetic of cinema vérité and the experiments of the Nouvelle Vague. This narrative device allows the viewer to identify with the character, to see the world through his eyes, and to share his emotions. It is an immersion in the protagonist's naivety and perseverance, made palpable by bold stylistic choices. Through the handheld camera, Keaton manages to capture the beauty and poetry hidden in everyday life. The scenes shot on the streets of New York, with people coming and going, cars speeding by, the noises of the city, acquire a particular charm, thanks to the spontaneity and realism of the images, transforming the metropolis into a dynamic co-protagonist, almost a living organism that swallows and then elevates the small, stoic cameraman. Finally, the monkey Josephine transcends the role of a mere comedic sidekick to become a catalyst for events, a symbol of that unexpected fortune or primordial instinct sometimes needed to overcome challenges, a kind of anarchic muse that leads to success where logic and tenacity alone fail. The Cameraman remains a melancholic and glorious testament to Keaton's genius, a last, bright flare of creative autonomy before the spotlights of major productions began, too soon, to dim on his uniqueness.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...