The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

1948

Rate this movie

Average: 4.50 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Three men searching for gold in Central Mexico will encounter every kind of adversity until they come face to face with their own souls, stripped bare of all human pretension. It is not merely a geographical odyssey, but a journey deep into the unconscious, a merciless unveiling of the most primal urges that civilization struggles to contain.

Greed, a despicable passion in which other deplorable vices can nest – from paranoia to brutality, from mistrust to homicidal madness – is rarely treated in films with the frank and ironic contempt that is vividly manifested in this work. Far from glorifying the pursuit of wealth as a driver of progress or personal fulfillment, Huston portrays it as a contagious disease, a poison that corrupts every bond, transforming brotherhood into a ring for the survival of the most desperate. It is an anti-fable of the American dream, a cynical and prescient reversal of the "self-made man" rhetoric, in which gold is not liberation but a condemnation, a weight that drags its devotees towards moral abjection. In this, the film anticipates, or at least enters into dialogue with, works that will explore similar recesses of the human soul, from Leone's later and more visceral Once Upon a Time in the West, to Paul Thomas Anderson's obsessive oil delirium in There Will Be Blood, while maintaining its own unmistakable and subtly bitter hilarity.

And certainly, Hollywood's great stars are rarely exposed in such a cruel light as that in which Humphrey Bogart is cast in this new image that Huston crafts for him. Light years away from the cynical but fundamentally honorable Rick Blaine of Casablanca or the astute Sam Spade of The Maltese Falcon, here Bogart embodies Fred C. Dobbs, a man who, under the pressure of the desert and the gleaming metal, progressively unravels, slipping into a paroxysmal paranoia that makes him as petty as he is tragic. It is a performance that redefines his acting archetype, demonstrating a rare versatility and courage for a star of his caliber, willing to sacrifice the aura of a hero to paint a portrait of human degeneration. It is said that Warner Bros. was initially reluctant to show Bogart in such an anti-heroic and repellent role, fearing for his image, but Huston's determination prevailed, gifting us one of the most powerful and unforgettable performances of his career, deserving of an Oscar which, ironically, went to John's father, Walter Huston, for his extraordinary role as Howard.

But the fact that this drama addresses such a dark recess of the human soul is a sign of originality and maturity. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is not merely an adventure film; it is an existential psychodrama disguised as a Western, an allegory of the transience of human desires in the face of nature's impassivity and the inevitability of fate. It represents a turning point, a work that had the courage to crack the narrative and moral conventions of classic Hollywood cinema.

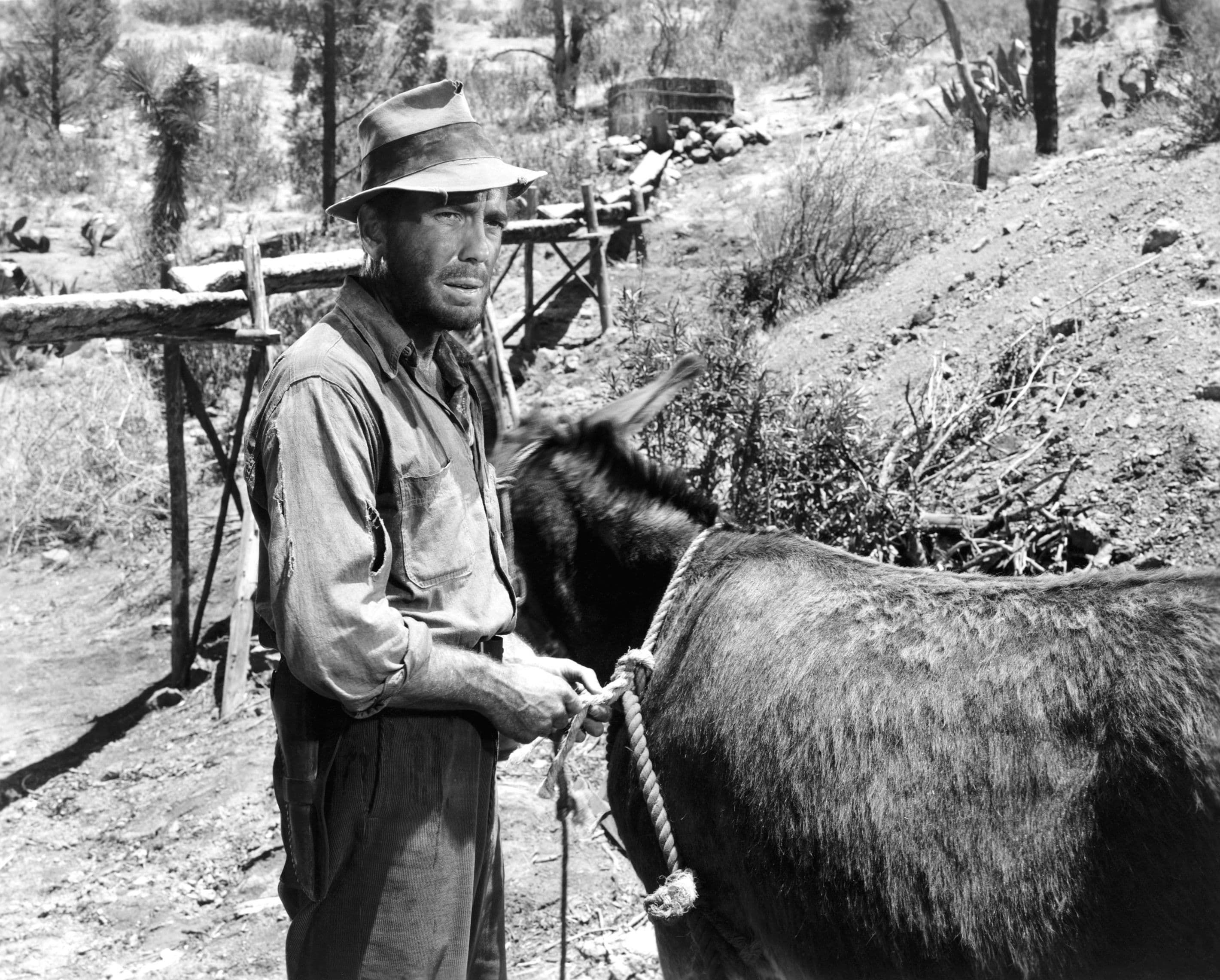

In this sense, John Huston achieves a revolution in Hollywood cinematic language, bringing the worst aspects of the human soul to the big screen, abandoning the safe confines of political correctness for a keen, transgressive, murky, and fascinating investigation. Huston, a unique auteur figure within the studio system, was known for his uncompromising vision and his inclination for stories of imperfect men, seeking often illusory or destructive goals. Here, his direction becomes lean, almost documentary-like, favoring outdoor shots in the impervious and dusty vastness of rural Mexico – a daring choice for the era that lent the film a raw and tangible realism. There is no room for sentimentalism or for the clichés of do-goodism; the characters are delineated with a moral complexity that defies easy categorization, their weaknesses are not narrative expedients but the lifeblood of the drama. Violence is not glorified, but shown in its brutal efficacy, a logical consequence of the dehumanization that gold provokes. In this, Huston aligns himself with a proto-noir sensibility, bringing to the screen not so much light and shadow, but the dust and mud of the human soul. It is a masterpiece of balance between epic and introspection, between grand landscape and inner misery.

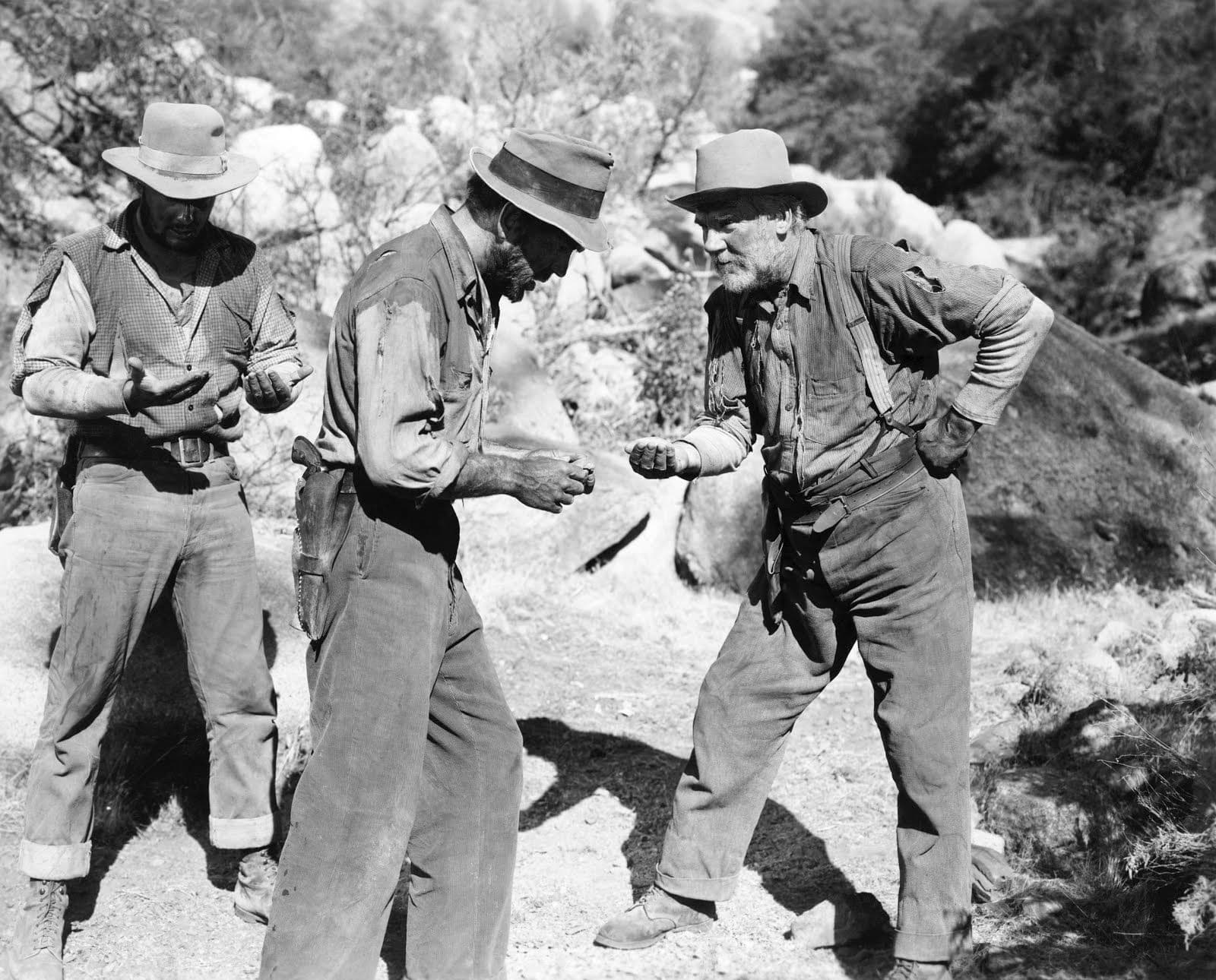

An unusual Humphrey Bogart, then, who stands out for a great display of acting prowess, whose physical and psychological transformation, from desperate homeless man to a man corrupted by his own obsession, is rendered with heart-wrenching depth. Beside him, Walter Huston delivers a memorable performance as Howard, the old prospector, a mix of folk wisdom and cynical pragmatism, who observes the downfall of his companions with an almost fatalistic clarity. Their interaction, and that with the more honest Tim Holt (Curtin), forms a dynamic trio whose alchemy is at the heart of the narrative.

Special mention goes to Ted D. McCord's cinematography, which renders pristine landscapes, glorious in their icy purity, in perfect disharmony with the unfolding events. The merciless sun carving through rocks, the wind stirring up dust, the silent and indifferent vastness of the Sierra Madre almost become a character in itself, a mute and grand witness to human pettiness. Natural light highlights the etched lines on the protagonists' faces, emphasizing their fatigue and the slow unraveling of their sanity, while wide shots of the mountain landscape underscore their insignificance in the face of nature's power, which ultimately reclaims everything, with a final, perfectly ruthless mockery.

An introspective, nuanced, and intelligent film, it rises beyond mere adventure storytelling to achieve the stature of a universal moral parable. Its timeless resonance lies not only in its extraordinary technical craftsmanship or masterful performances, but in its ability to explore with bitter clarity the darkest deviations of the human soul, demonstrating how true wealth is perhaps the only thing money cannot buy, and that the irony of fate can be the greatest, and most liberating, of jests. An enduring classic, whose lesson remains more relevant than ever today.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...