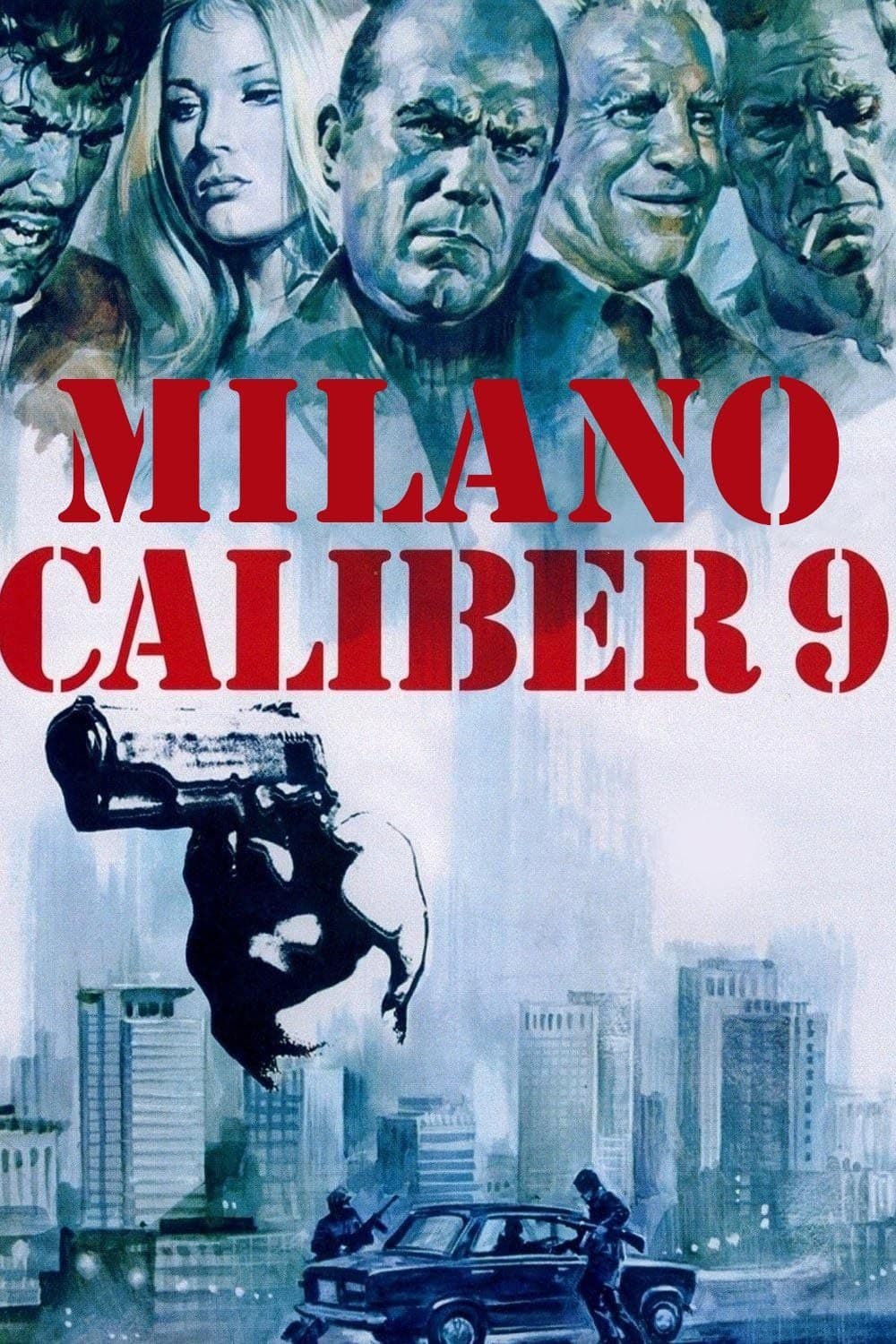

Caliber 9

1972

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Scerbanenco creates, Di Leo directs, Moschin embodies.

This work can be summarized as an creation where Noir, Thriller, and Gangster Movie blend their stylistic elements, generating an archetype that would later define a distinct genre: the Italian crime film, later much admired by directors like Tarantino and Rodriguez. But reducing Milano Calibro 9 to a mere synthesis of genres would be a cardinal sin, as it stands as a cornerstone of a cinematic movement, the poliziottesco, which brutally and effectively captured and reflected the paranoia and tensions of an Italy suspended between the economic boom and the Years of Lead. It was not merely a fusion, but a distillation: Di Leo took the archetypes of American noir, the tension of European thriller, and the raw violence of the gangster movie, and immersed them in a boiling Italian social context, delivering a stark and disturbing portrait. Quentin Tarantino's admiration, evident in the tribute in Pulp Fiction (the briefcase, the silent anti-hero, a certain dialectic between irony and brutality) or in the cool aesthetic of Jackie Brown, and Robert Rodriguez's, who borrowed Di Leo's pulp energy and stylization of violence, is no coincidence, but rather the acknowledgment of a cinematic lesson learned and reinterpreted.

The story revolves around Scerbanenco's collection of short stories of the same name, specifically the story “Stazione Centrale ammazzare subito” (Central Station, Kill Immediately). It is the story of a criminal, Ugo Piazza, who, after serving 3 years in prison, is suspected by his former gang members of having pocketed a substantial haul. His odyssey begins to clear himself of the accusation and find the true culprits. Di Leo's adaptation is not slavish, but a brilliant re-elaboration that captures the essence of Scerbanenco's prose – an implacable fatalism, metropolitan alienation, and a profoundly cynical view of the human soul – amplifying its existential violence and narrative urgency. Scerbanenco, master of the "Milanese giallo" (crime novel), had already painted a cold and indifferent metropolis, but Di Leo infused it with a life of its own, pulsating with traffic, noise, and organized crime that evolved, becoming more sophisticated beyond the codes of honor of Southern Italy.

The line, famous and precognitive: “If things continue like this, they’ll have to create an anti-mafia force even in Milan.” This phrase, spoken with disillusioned lucidity, transcends its dialogic function to become a warning, an almost documentary-like prophecy. It evokes the criminal effervescence that in the 1970s was transforming Milan from an economic capital into a crossroads of illicit trafficking and new, ruthless organizations, anticipating by decades the full awareness of mafia entrenchment in the North. It is a stroke of genius that indissolubly links the fictional narrative to the chronicle of a changing country, where crime was no longer a marginal or exclusively geographical phenomenon, but a metastasis invading the social fabric.

The excellent editing gives the narration a tight pace. But Di Leo's mastery goes far beyond mere pacing. His direction is a sensory experience: in every frame, the director's precise hand is evident in rendering the sordid atmospheres of the story, coupled with a didactic attention to the Milanese setting. Di Leo transforms Milan into a character in its own right, with its oppressive alleys, aseptic modern districts, and smoking factories, giving the city a powerful visual identity. The camera is nervous, almost obsessive, moving fluidly between breathtaking chases and tight close-ups that delve into the protagonists' marked faces. Violence is never gratuitous, but an expression of a world without redemption, although stylized with an almost choreographic elegance that would become a distinctive feature of the genre. The innovative use of music, with Luis Bacalov's soundtrack ranging from jazz-funk to the psychedelic rock of the legendary Osanna – whose "Tema di Milano Calibro 9 (Gangster Story)" is an icon of Italian cinema – elevates the experience, amplifying the sense of unease and ineluctability.

A final mention for Moschin and his glacial gaze, capable of seducing ballerinas and stopping bullets mid-air. Gastone Moschin embodies Ugo Piazza with a stoic and almost Buddhist impassivity that makes him unforgettable. His face, gaunt and harsh, is a canvas onto which a deep existential weariness is projected. Ugo is not a hero seeking redemption, nor a villain thriving in evil; he is a man caught in a perverse mechanism, traversing a personal hell with an almost silent dignity. His performance is a masterpiece of subtlety, where every small gesture, every variation in his gaze, communicates volumes of pain, paranoia, and a lucid awareness of his own condemnation. Alongside him, a first-rate cast helps forge the legend: Barbara Bouchet, in the role of Nelly Bordon, embodies a femme fatale, yes, but with a fragility and independence that elevate her beyond mere stereotype; Mario Adorf, as the brutal Rocco Musco, is the personification of blind and irrational violence; and Philippe Leroy, as the "Chinaman," brings a touch of elegant, almost philosophical, cruelty, providing an intellectual counterpoint to brute force. Milano Calibro 9 is not just a genre film; it is a visceral essay on betrayed trust, the corrupted nature of power, and the illusion of justice in a world that has lost its moral compass, a cornerstone that continues to speak with a surprisingly relevant voice.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...