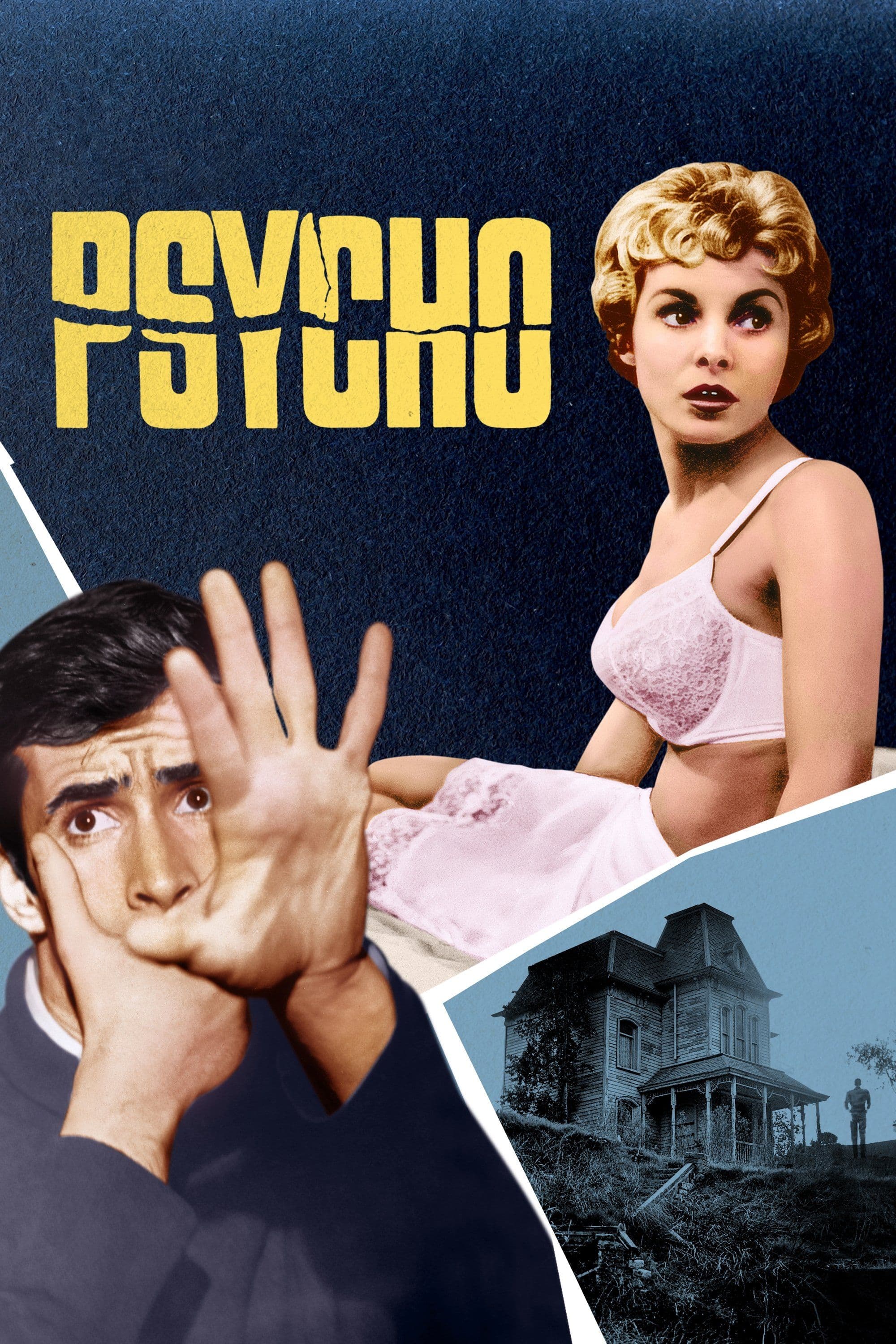

Psycho

1960

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Hitchcock delves into the murky depths, directing his sharp gaze into the psyche of a deviant and paranoid motel manager. The Master of Suspense doesn't just skim the surface; he plunges into the darkest depths of the human soul, revealing the unsuspected cracks that can lie hidden behind the most commonplace of facades, that of a motel on Highway 10. It is a chilling descent into the unconscious, where horror is not supernatural, but endemic, a latent pathology in everyday life.

The history of this film is particularly troubled, as no producer believed in the project, an almost inexplicable obstinacy considering the artistic credentials of the original novel's author, Robert Bloch, and especially the pedigree of Hitchcock himself, fresh from acclaimed commercial successes like "North by Northwest." Yet, the thematic audacity – the murder of a protagonist halfway through the film, the extreme psychological implications, the choice to shoot in black and white with a deliberately reduced budget to maximize profit and mask the brutality of certain scenes – frightened the major studios. This rejection prompted Hitchcock, with his unmistakable visionary boldness, to produce the film himself, an act of artistic rebellion that underscored his unyielding conviction. To do so, he faced considerable financial problems, even going so far as to mortgage his own home to cover the costs, an anecdote that testifies to his unwavering faith in the revolutionary potential of the work. He knew he had not just a good film on his hands, but something epochal, and he firmly believed in himself and his ability to forge a new cinematic paradigm.

As we know, events proved him right, and thanks to his tenacity, one of the greatest masterpieces in cinematic history was thus able to see the light of day, effectively ushering in an era for psychological thrillers and modern horror. Its release was accompanied by an unprecedented, almost paranoid, marketing campaign that prohibited entry into the cinema once the viewing had begun, an imposition aimed at preserving every single surprise, every narrative twist, making the viewer complicit and victim of Hitchcockian manipulation.

A woman, an accounting clerk for a firm, steals forty thousand dollars and flees, finding refuge in a Motel. Her fate, seemingly tied to the suspense of a getaway and the search for redemption, proves to be a mere pretext. The owner, a somewhat quirky fellow, affable in his clumsiness, courteously welcomes her, only to then find her dead, stabbed in the shower by his ailing mother. This bold and iconoclastic narrative choice, eliminating the protagonist in the first act, shattered all audience expectations, plunging them into an abyss of uncertainty and unexpected horror. Norman Bates, distraught by what happened, or so it seems, puts the body in the car's trunk and makes everything disappear by throwing the car into the quicksand, a gesture that is not just concealment of a corpse but a visual metaphor for sinking into an abyss of guilt and madness from which there is no escape. A private investigator, hired by the victim's fiancé, will stubbornly try to shed light on the case, following clues through a labyrinth of hints and red herrings that will inevitably lead him toward the pulsating heart of darkness.

A magnificent Anthony Perkins, in the role of a lifetime, embodies a Norman Bates who becomes the archetype of the shadow lurking behind reality, the specter that looms over our peaceful lives. His performance is a masterpiece of subtlety and progression, transitioning from awkward shyness to a lucid, terrifying madness, an unforgettable portrayal that marked his career and the history of cinema. Perkins does not portray a monster, but a victim of his own pathology, a man torn apart by a distorted Oedipal complex that makes him both tormentor and prisoner. He is the next-door neighbor who might conceal a universe of unspeakable perversions, the embodiment of a dysfunction no longer confined to psychiatric hospitals but lurking in the heart of small-town America.

Glorious, and deservedly legendary, is the shower scene in which the killer approaches backlit behind the curtain, pulls back the curtain and stabs, stabs, and stabs. The sequence, a tour de force of cinematic editing, with its 77 cuts in less than 45 seconds, never shows the knife penetrating flesh, nor blood flowing profusely. It is the suggestion, the implied violence, and the sonic crescendo of Bernard Herrmann's screeching violins that imprint the horror on the viewer's mind. As the blood (chocolate syrup, in reality, for greater contrast with the black and white) inexorably drains into the shower drain, Hitchcock lingers on the details that make the scene chilling: the shower's flow, the drain with water swirling around it, a vortex reminiscent of the victim's glassy eye and the maelstrom of madness about to engulf everything. It is a macabre ballet of fragments that assemble an agony, a purely cinematic experience that redefined the concept of violence on screen and indelibly influenced the entire horror genre, paving the way for all future slashers, while remaining unrivaled for its psychological mastery rather than explicit brutality.

Perhaps one of the first works of such resonance to address the theme of personality dissociation and its criminal implications with such clinical precision and devastating impact. "Psycho" is not just a film about madness, but also a profound investigation into voyeurism, sexual repression, and the chameleon-like nature of evil. It is a masterful demonstration of how suspense does not derive from "what" will happen, but from "how" and "why."

A film that will make you nervously look out the window, that will make you doubt appearances, and that might make you choose your next hotel room very carefully, or perhaps, simply, make you prefer not to travel alone anymore. Its echo, over sixty years after its release, still resonates in our deepest fears, confirming "Psycho" not only as an enduring classic, but as an inescapable pillar of popular culture that continues to disturb and fascinate.

Country

Comments

Loading comments...