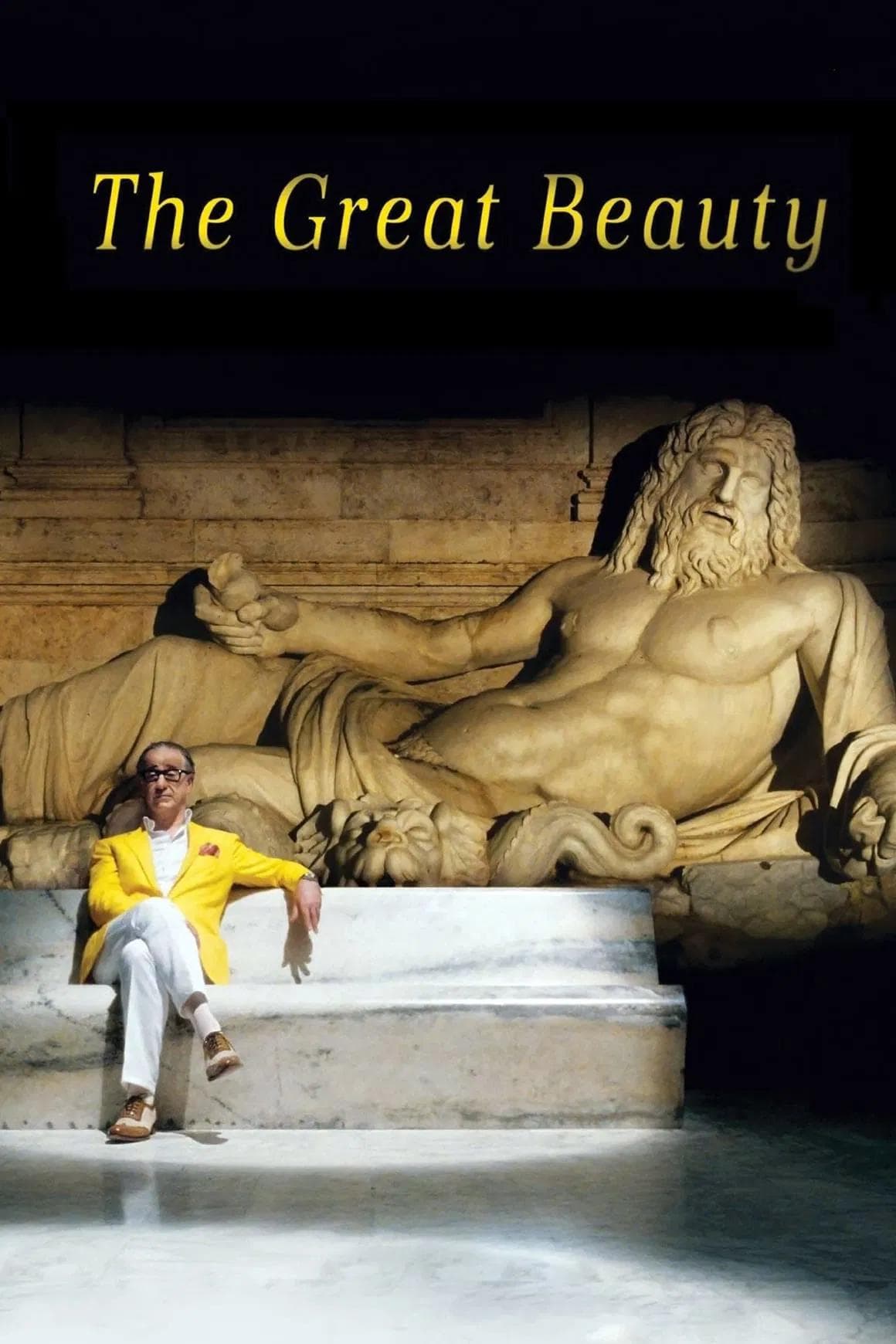

The Great Beauty

2013

Rate this movie

Average: 3.50 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Among all the Italian talents poised to revitalize the film industry of Visconti’s native land, Paolo Sorrentino was not the easiest to approach for a long time, and for good reason: from film to film, his style increasingly ensnared the viewer through the extreme use of narrative and directorial artifices. While these created a unique and unrepeatable cinematic dimension, they also alienated a significant portion of the audience reluctant to engage with complex interpretations.

Nevertheless, looking back at his filmography, we discern an undeniable continuity: a clear penchant for "empty" beings in whom a certain emotional cowardice coincides with a latent weariness of life, a degeneration of talent that almost leads them to vegetate. From the mysterious stranger in The Consequences of Love to the tired, quirky rocker in This Must Be The Place, to the disillusioned dandy in The Great Beauty, these are characters trapped in a static context, engulfed by their own cynicism and unable to interact with their surroundings and others without causing themselves harm. The key to Sorrentino’s cinema lies precisely in this thematic choice and all that it implies in visual terms: depicting a character's interaction with a hostile environment. Certainly, one might feel annoyed seeing him play like a meticulous chemist dissecting his characters with a camera: his obsessive close-ups, his microscopic details of a face, an expression, a gesture. Yet, The Great Beauty is in this sense the culmination of Sorrentino’s art, managing admirably to make narcissism and essentiality coexist, delivering the image of a character who will remain in the history of Italian Cinema. A profound sense of contemplation permeates this film, forcing the eye to surrender to the sensual rhythm that the director imposes on the story. The success of this film stems precisely from this: having masterfully conveyed through images how Jep Gambardella remains obsessed with an elusive ideal that he cannot find. He senses it, perceives it, brushes its edges, but is perpetually disillusioned by it.

The film opens with two scenes that are in stark contrast yet ultimately complementary: the opening scene reveals the Janiculum Hill with sumptuous camera movements and a background musicality from a women's choir. With a bewitching, dreamy gaze embracing all of Rome, Sorrentino begins his personal journey through the Eternal City. It is a journey, as Celine says in the opening epigraph, poised between dream and reality, between evanescence and substance. Then suddenly we are abruptly awakened by a Japanese tourist collapsing before the beauty of Rome. This is the unifying thread that energizes the second scene, which opens on a grotesque party on a Roman terrace where Bob Sinclar and Raffaella Carrà dictate furious rhythms to a diverse crowd writhing in a night reminiscent of La Dolce Vita. Behind the exuberance and ecstasy of the dance, behind the desire to get lost in these parties and dissolute nights, we perceive something hidden, a kind of melancholic thread radiating from the face of Jep Gambardella, the evening's guest of honor. This elegant, disillusioned man, with an ironic glimmer flickering in his eyes, has arrived at the last party of his life. He stops amidst the vortex of the dance, and seems to freeze, lost in thought, while around him rages the clamor of zombies thirsty for life. His malaise is a snobbish sentiment that has crossed all bounds: living in the memory of a literary masterpiece on which everyone has something to say (even if they haven't read it), becoming a social journalist to "finally ruin the evenings I attend." An intangible dissatisfaction, in short, that devours him and prevents him from savoring life as he wishes.

His sole refuge remains misanthropy, a realm in which he excels and which tends to keep him balanced daily on the brink of the abyss: and so, to survive, he must humiliate a somewhat too bourgeois friend, a pseudo-guardian of morals whom Jep can no longer tolerate. His breaking point is near. He must react. He therefore sets a goal: to regain lost dignity, and the signs of this turnaround are not lacking: a tragedy strikes him unawares (a woman he had known long ago, who had continued to love him in secret, has died). He thus clings to eminently grotesque scenes, contemplating their slightest nuances each day. Examples? A maiden with pubic hair painted in the colors of the Soviet flag who rushes headlong into a wall, high-ranking, vacuous figures attempting to fill the void of their existence with discussions about Ethiopian jazz or "Pirandellian" hair dye, a cosmetic surgeon who injects Botox into clients whom he wishes to be "friends" with, a cardinal who sets aside spiritual reflections to extoll his culinary skills, a child who exorcises her anger by doing action-painting in front of a hypnotized crowd, a teenager so obsessed with the writings of great authors that he literally devours them, becoming an embodied testament to them, even if it means appearing naked and painted red.

A whirlwind of scenes and images that compose, like small mosaic tiles, the soul of this embittered aesthete, of a man attempting to halt the drift of his spirit by cradling himself in memories, by a life slipping through his fingers. And it is precisely in this undercurrent of despair that Sorrentino's film captivates. From this searing frustration, an unprecedented beauty emerges, an almost superhuman feeling that blossoms for Jep when Stefano opens the doors of Rome’s most beautiful palaces to him, a poignant perfection that surrounds him, surrounds us, and that, reaching out to grasp it, inexplicably eludes him, eludes us. A Great (lost) Beauty.

Main Actors

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...