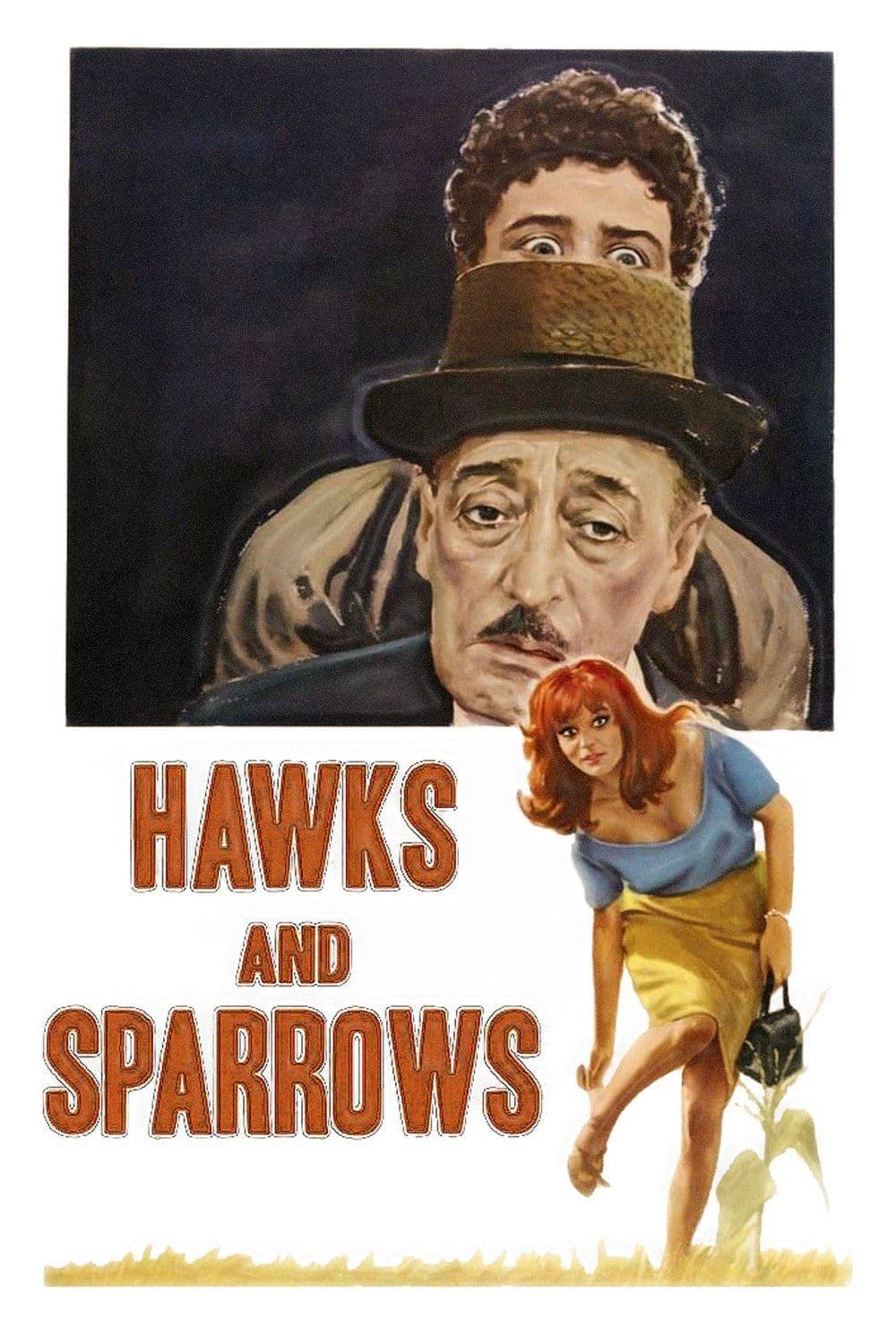

The Hawks and the Sparrows

1966

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Pasolini, ironic, sardonic, delightfully hilarious, grapples with religious matters and mystical themes, but does so with a lightness that is pure conceptual audacity. In Hawks and Sparrows, the Roman director dismantles the sacred with the same reverence with which he had explored it in The Gospel According to St. Matthew, infusing every frame with a fizzing dialectic between faith and materialism, between transcendence and crude immanence. It is not a desacralization for its own sake, but rather an exploration, playful yet profoundly serious, of spirituality in an era of rampant secularization, an inquiry into the possibility of an earthly, dirty, intrinsically human "holiness."

A father and his son, the memorable Totò and Ninetto Davoli, are recruited into Saint Francis's celestial army by a talking crow and begin their pilgrimage on the crude and corrupted earth. This premise, which in itself evokes the moral fable, is the launching pad for one of Pasolini's most acute and moving allegories. The crow is not a mere narrative device; it is the very voice of the intellectual, Pasolini's own critical conscience, a kind of enlightened philosopher who dispenses Marxist maxims and digressions on "Protestantism" as a historical and cultural force, unveiling the hypocrisies and violence hidden beneath the mantle of tradition. Its erudite logorrhea contrasts comically and tragically with the almost childlike simplicity of the two pilgrims who, though not fully grasping the subtle arguments, absorb their essence with the innate wisdom of the common people. This triple journey – the ideal, the popular, and the critical – merges into a narrative unicum that is pure theater of the absurd and at the same time an intense reflection on the human condition.

They will come to know the sorrows, ugliness, and abuses to which simple men are subjected, attempting to bring a word of comfort. But it is a comfort that often proves illusory, a denunciation of the unfulfilled promises of progress and religion. Theirs is a Via Crucis without final redemption, a wandering through an Italy in transition, that of the economic boom that was dematerializing the "people" Pasolini loved and studied, transforming them into a consumer mass. They move between squalid suburban brothels, desolate countrysides, and the indifference of a society losing its peasant innocence to embrace an uncertain future and, in the poet's eyes, devoid of sacredness.

A vision always focused on social implications, an eye always fixed on the humblest people from whom the narrative's vividness, its most candid form, arises. This film is a testament to his obsessive attention to the "subproletariat," to the most authentic and "pure" part of the country, before it was corrupted by modernization. The narrative, though steeped in surrealism, maintains a deeply rooted adherence to tangible reality, to not only material but also spiritual poverty, typical of Pasolini's cinema which, while abandoning pure Neorealism, retains its accusatory power and love for the marginalized. It is through these marginal, often anonymous figures that Pasolini reveals his deepest emotion, a lyricism that rises from the concreteness of their existences.

A denunciation through images and the natural lyrical force that springs from them, as often happens in Pasolini's work. The choice of stark, almost documentary black and white lends the sequences a timeless and almost archetypal aura, accentuating the contrast between the lightness of the fable and the gravity of the themes addressed. Every shot is a visual poem, an essay in aesthetics that elevates the mundane to symbol, the small gesture to universal metaphor. The direction is stark and precise, yet it lets profound emotion shine through, almost a tenderness for his characters and for the Italy that was disappearing.

As in The Gospel, in Hawks and Sparrows Pasolini also appears drawn to the mystical spirit that arises from Holiness, only to then direct this celestial tension towards the earth and its most contingent needs, its most ignobly earthly affairs. But here, holiness cracks and merges with human innocence more than with divinity. It is the "theology of the crow" that is challenged, the logic of the intellect that clashes with the hunger and thirst of the body. The ending, with the metaphorical banquet of the crow itself, is a powerful and crude image: knowledge (the crow-intellect) is absorbed, swallowed, and metabolized, not as an act of sacralization but as a primary necessity, almost indicating the impossibility of pure intellectual abstraction in the face of hunger and the world's concreteness. It is an act of intellectual cannibalism, in which theory must give way to survival, or perhaps, in which theory becomes flesh and merges with it.

Totò pushes his art into the tragic, the comic, the vaudeville, with a breathtaking lightness, almost a final, sublime swan song. His performance is an absolute masterpiece, a perfect synthesis of his comedic mask and his surprising ability to convey a profound melancholy, an innate popular wisdom. Pasolini, with a brilliant and counter-current intuition, extracts from Totò the essence of the Italian "poor soul," an archetype that transcends his iconic comedic persona to become a universal symbol of the simple man, perpetually poised between hope and disillusionment. His physicality, his gazes, his clownish yet dignified gait, lend the film an unforgettable human resonance. The illness that would soon take him was already evident, yet Totò, with an almost unearthly energy, gave himself entirely to the role, making his character a paternal figure, fragile and powerful at once, a final, moving embodiment of a disappearing Italy and a type of cinema that still knew how to look into the eyes of life's and death's mystery. His presence is a bridge between popular cinema and art-house film, a living lesson on how comedy can be elevated to philosophy, a smile to tears.

A film of rare beauty, an atypical and courageous work that never ceases to question, provoke, and move, confirming Pasolini as one of the greatest intellectuals and filmmakers of 20th-century Italy, capable of transforming pain into poetry and polemic into vision.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...