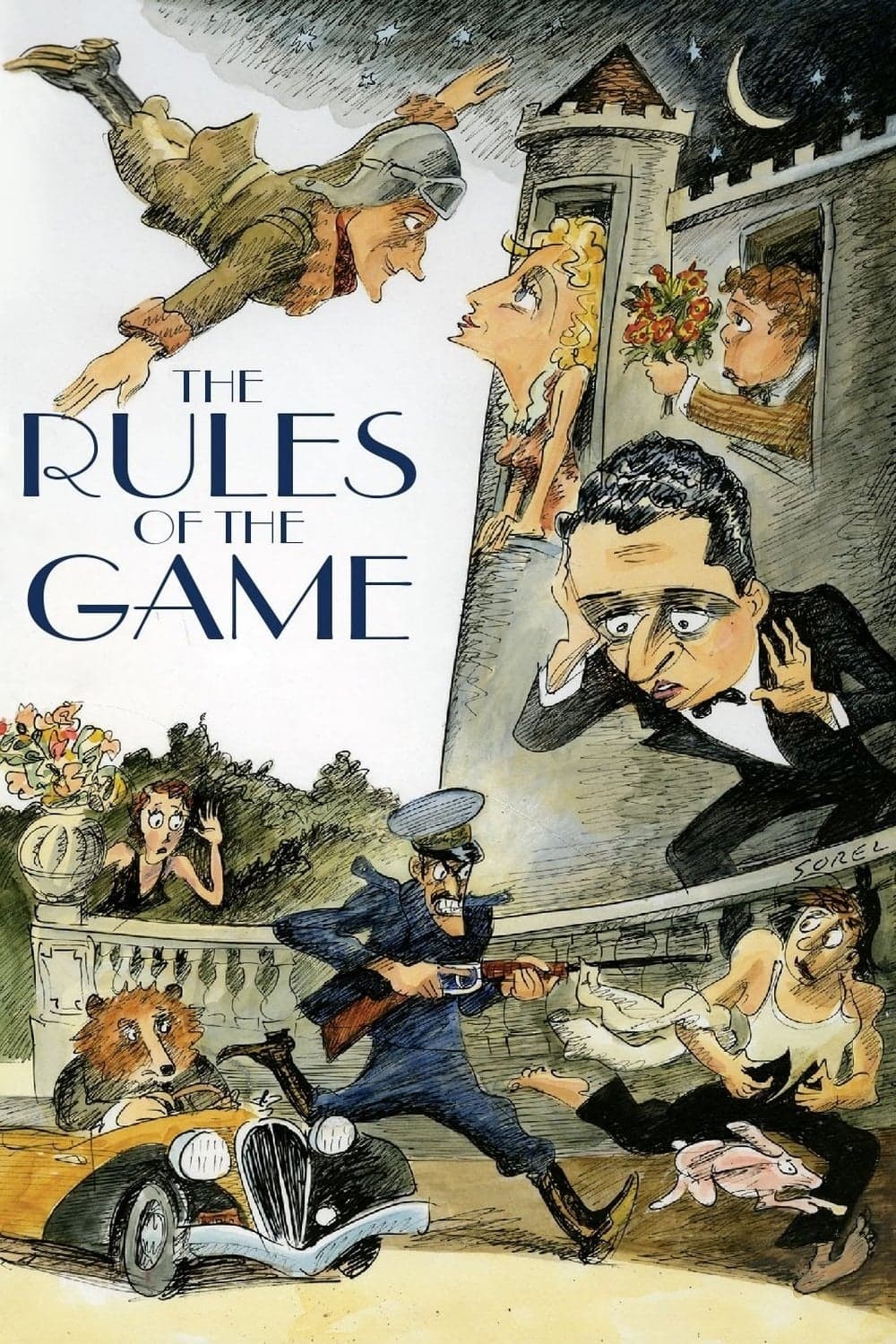

The Rules of the Game

1939

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The Rules of the Game is a satirical and disillusioned fresco of French high society on the eve of World War II. An era suspended in a precarious balance, where lightness was already turning towards imminent gravity, and bourgeois frivolity posed as a last, desperate dance on the edge of the abyss.

Jean Renoir stages a microcosm of frivolous and superficial characters, trapped in a game of complicated and hypocritical love affairs. A ballet of masks and pretenses, where every feeling, every passion, even every pain, seems to be merely a pawn in a perpetually ongoing game.

The film, through a skillful intertwining of comedy and drama, reveals the contradictions and weaknesses of a social class clinging to obsolete rituals and conventions, ignoring the world collapsing around them. What is staged is not just a chronicle of adultery and jealousy, but a merciless autopsy of an aristocracy and financial bourgeoisie incapable of reading the signs of an impending catastrophe, taking refuge in an illusory bubble of privilege and frivolity.

The Rules of the Game is a film that surprises with its modernity, with its ability to anticipate themes and styles that would later be developed by modern cinema. It is a work that, while firmly rooted in its time, boldly projects itself towards the future, foreshadowing the expressive freedoms of the Nouvelle Vague and the narrative nonchalance that would characterize post-war cinema.

Renoir's direction, fluid and dynamic, uses long takes and deep focus to create a sense of realism and immersion in the story, transforming the viewer into a discreet observer, almost a voyeur, of a drama that unfolds seamlessly. This stylistic choice is not mere technical virtuosity; it allows the characters to move freely within the frame, revealing their complex interactions and the social stratification of the environment, anticipating theories on ambiguity and viewer interpretive freedom that would be celebrated by André Bazin. It is a realism that does not merely reproduce the surface but delves into the collective psyche of an era.

The dialogues, brilliant and often cruel, reveal the hypocrisy and superficiality of the characters, shaping a film that provokes thought and disturbs, a work that lays bare the weaknesses of human nature and the contradictions of society. Every line is a stab, a scathing comment that demolishes the façades of respectability.

A glossy melodrama in which Eros and Thanatos dance until the very end with effortless grace. The hunt, which should be a playful and orderly ritual, transforms into a brutal metaphor for the barbarity inherent in the human soul and for social predation, where death, both of animals and later of a man, is met with an almost indifferent cynicism, like a mere incident in a larger game.

Renoir once again astonishes with his no-holds-barred realism, in which naked truth is publicly exposed without any sense of disillusionment, but with an almost surgical lucidity.

At a large country estate, La Colinière, a group of aristocrats and bourgeois gathers for a weekend of hunting and parties. A claustrophobic microcosm, a kind of ship of fools sailing towards shipwreck.

Among the guests are Marquis Robert de la Cheyniest, a wealthy collector of mechanical toys (perhaps a symbol of the artificiality and manipulation permeating his relationships), and his wife Christine, a charming and dissatisfied woman.

Robert is in love with Geneviève, a stage actress, while Christine is courted by André Jurieux, a war hero aviator. A sincere and passionate man, whose romantic honesty is destined to clash with the conventions of a world that has lost all authenticity.

The love affairs intertwine and become complicated, in a game of seductions, betrayals, and lies. Lying, in fact, is not a moral flaw, but the rule itself, the social lubricant that allows these parallel lives to flow without apparent friction.

The servants of the villa are also involved in their masters' love affairs, creating a parallel between the dynamics of high society and those of the "world below." A parallel that reveals how the same impulses, the same weaknesses, pervade every social stratum, but are handled with very different codes and consequences, sometimes more brutal, in the "lower" world. Marceau, the poacher, and Schumacher, the gamekeeper, with their elemental passions, are a mirror and counterpoint to the sophisticated hypocrisies of the nobles.

The weekend concludes tragically, with an accidental murder that disrupts the apparent social order and conventions. The tragedy, however, is quickly covered up, and life resumes as if nothing had happened, showcasing the hypocrisy and superficiality of a world that refuses to face reality, preferring convenient amnesia to uncomfortable truth. The final act is not a catharsis, but a confirmation of that society's pathological indifference.

Initially censored and then repudiated by audiences and critics, burned and mutilated, it was rediscovered in subsequent years, becoming a classic of French and world cinema. Its initial failure was likely due to its uncomfortable truth: the 1939 audience was not ready to see itself reflected in such a merciless image on the eve of a war that would sweep away an entire civilization.

The film has been interpreted as a fierce critique of the hypocrisy and decadence of French high society on the eve of World War II. An indictment against an entire ruling class guilty of blindness and self-deception.

Renoir, with a clear-sighted and disillusioned gaze, lays bare the contradictions of a world clinging to superficial rules and conventions, ignoring the real problems and social tensions afflicting it. His social critique would later be taken up by another great of the 20th century, Luis Buñuel, with whom he shared the sharp insight into the absurdity of bourgeois rituals.

But while Renoir employs a realistic approach, observing reality attentively and highlighting its contradictions like a social ethnologist, Buñuel uses surrealism to create absurd and dreamlike situations that reveal society's irrationality and hypocrisy. Both directors, however, use an ironic register and the tool of satire to unmask the vices and weaknesses of their characters and the society they represent, paving the way for auteur cinema that would later influence generations, from Rossellini's Italian Neorealism to the Nouvelle Vague, which would recognize Renoir as one of its spiritual fathers.

The uninhibited use of dialogues as sharp blades within often extemporaneous scenes is employed to create a growing sense of suspense, disorientation, and alienation in the viewer. A cognitive dissonance that generates true, profound unease.

Renoir's work, which we rediscover today, appreciating its extraordinary modernity and wonderful dialectical charm, is a film that continues to speak to us about human nature, its fragilities, and the eternal, tragic rules of the social game.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...