Wild Strawberries

1957

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Isak Borg is a retired chief physician of medicine who is traveling to Lund University to receive a lifetime achievement award. His journey promises to be a final, ritual public consecration of an irreproachable existence, almost impeccable in its rigorous adherence to intellectual and academic logic. Yet, beneath the surface of bourgeois respectability, there harbors an emotional aridity and a moral solitude that not even the most prestigious of honors can conceal.

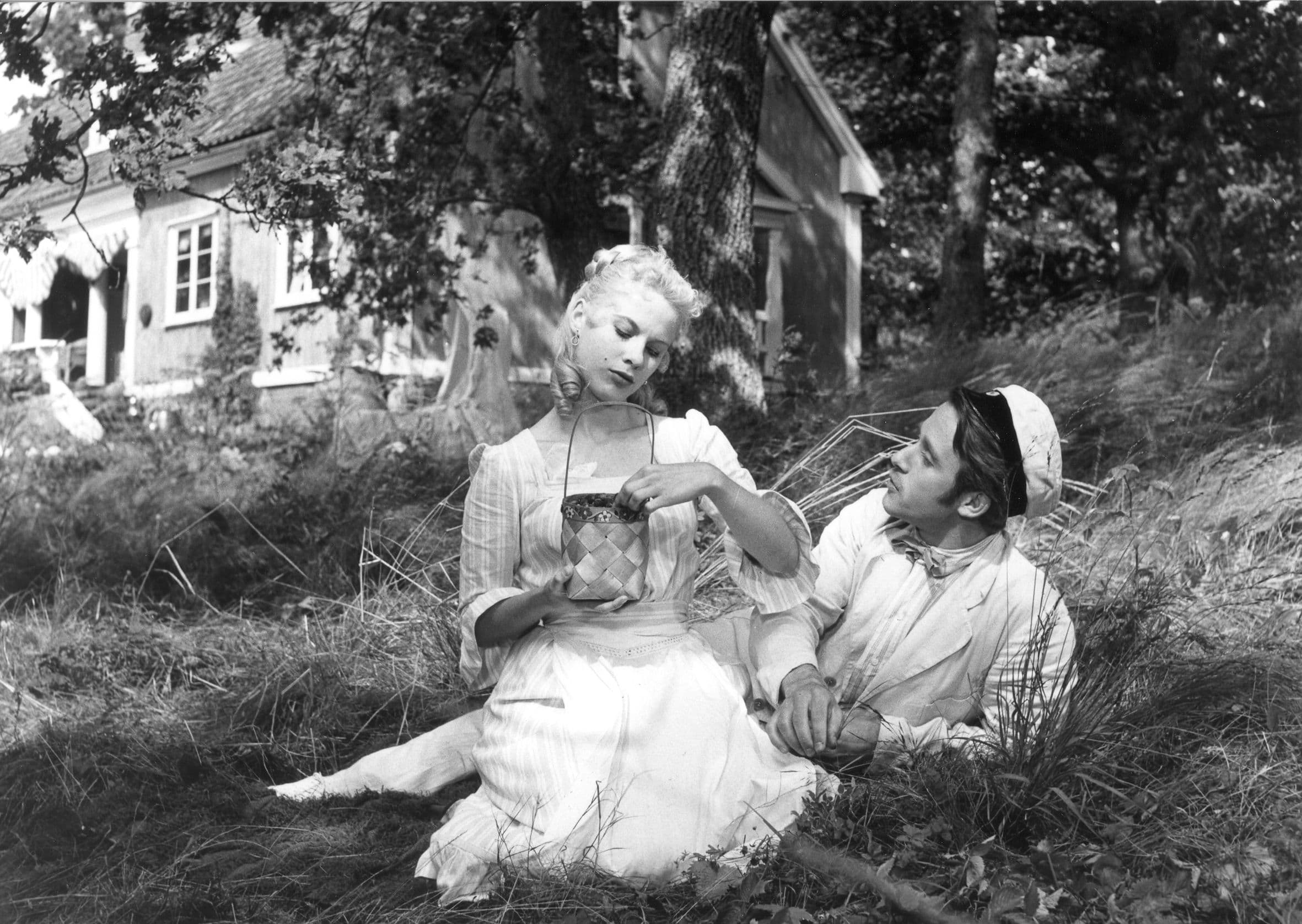

During the journey, he will face nightmares and hallucinations that will present him with a different past in relation to the choices he made. These are not mere phantoms of the mind, but true abysses opening onto the unconscious, brutal tears that rend the veil of his self-deceiving composure. Through vivid and disturbing dream-like sequences, Bergman drags us into the spiral of Isak's psyche, forcing him to confront his emotional failures, his character rigidities, and the egoism that has marked his relationships with his wife, his son, and even his beloved cousin Sara, the embodiment of a lost and idealized love. Time, symbolized by clocks without hands or by a funeral where Isak himself is the deceased, reveals itself as an implacable tyrant demanding a reckoning, not only of professional successes, but of lived life and cultivated affections.

The journey will become an instrument of catharsis, balanced between redemption and damnation. It is an interior odyssey, a pilgrimage of the soul recalling the descents into the underworld of epic tradition, although here the underworld is the most recondite folds of a human existence. The vehicle, a car in which the road winds through memories, becomes a means to navigate the vast sea of memory, amidst regrets and glimpses of a now unreachable childlike joy.

When, during this fateful journey, he encounters three young people who ask him for a ride, it will be an opportunity for him to put himself on the line, shaking off anguish and aridity. These young people, emblems of a lost vitality and lightness, serve as an unsparing mirror and, at the same time, as catalysts for a possible awakening. Their lively dialectic on life, death, love, and religion, while only skimming the surface of Isak's skeptical mind, begins to erode his defenses, forcing him to reconsider the aridity of his own heart and the illusion of being able to live exempt from the chaos of human emotions. Their spontaneity and thirst for life contrast sharply with his refined nihilism, offering him a final, unexpected lesson on the beauty of surrendering to the existential flow.

Bergman plays, especially in the first part of the film, between dream and reality, revealing before the vigilant eye of his camera the decomposition of a mind through its fears, something similar to the work Sigmund Freud performed on his patients through the analysis of dream content. It is not just a learned citation, but the application of a methodology that Bergman, with his unparalleled psychological acuity, transforms into cinematic language. Gunnar Fischer's camera becomes a probe, penetrating the unconscious with a visual audacity that anticipates the cinema of the psyche by decades. The images do not merely illustrate the subconscious, but create it, making it tangible, almost palpable in its suffering and mystery. The direction is an analytical session in motion, where every frame is a fragment of memory, a projection of fears, an attempt to decipher the secret code of a soul in crisis.

And it is precisely the dream sequences that recall German Expressionism, to which Bergman evidently pays tribute. The echo of masterpieces like Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is not only stylistic but profound: Expressionism aimed to make inner torment visible, to deform reality to reflect the state of mind, and Bergman absorbs its lesson to construct a gloomy and unsettling mental landscape. The sharp lights and shadows, the evocative set designs, and the close-ups that capture the expression of an atavistic terror are not merely aesthetic choices, but tools to expose human fragility in the face of death, regret, and the inescapability of time. The "Wild Strawberries," the metaphor for the place of lost innocence, is in this context a shard of light and nostalgia that contrasts with the dense shadow of Isak's present.

In essence, a film that unfolds its entire art of psychological introspection, stripping man bare as a thinking being and providing us with an access code to his most intimate memories. Bergman does not merely portray a crisis of conscience but investigates the possibility of a late redemption, the courage to confront one's own demons to find inner peace. Wild Strawberries thus stands as one of the pinnacles of Bergmanian cinema, a work that, like Persona or Whispers and Cries, delves uncompromisingly into the depths of the human soul, revealing its wounds but also its capacity for spiritual purification. It is a reflection on life, death, and the meaning of existence that transcends the individual, becoming universal.

A sort of mental picklock, lacerating and lysergic, that unhinges the doors of the soul and returns to us, with rare poetic intensity, the moving and brutal portrait of a man who, in the twilight of his life, finds the strength to look himself in the eye and, perhaps, to forgive himself.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...