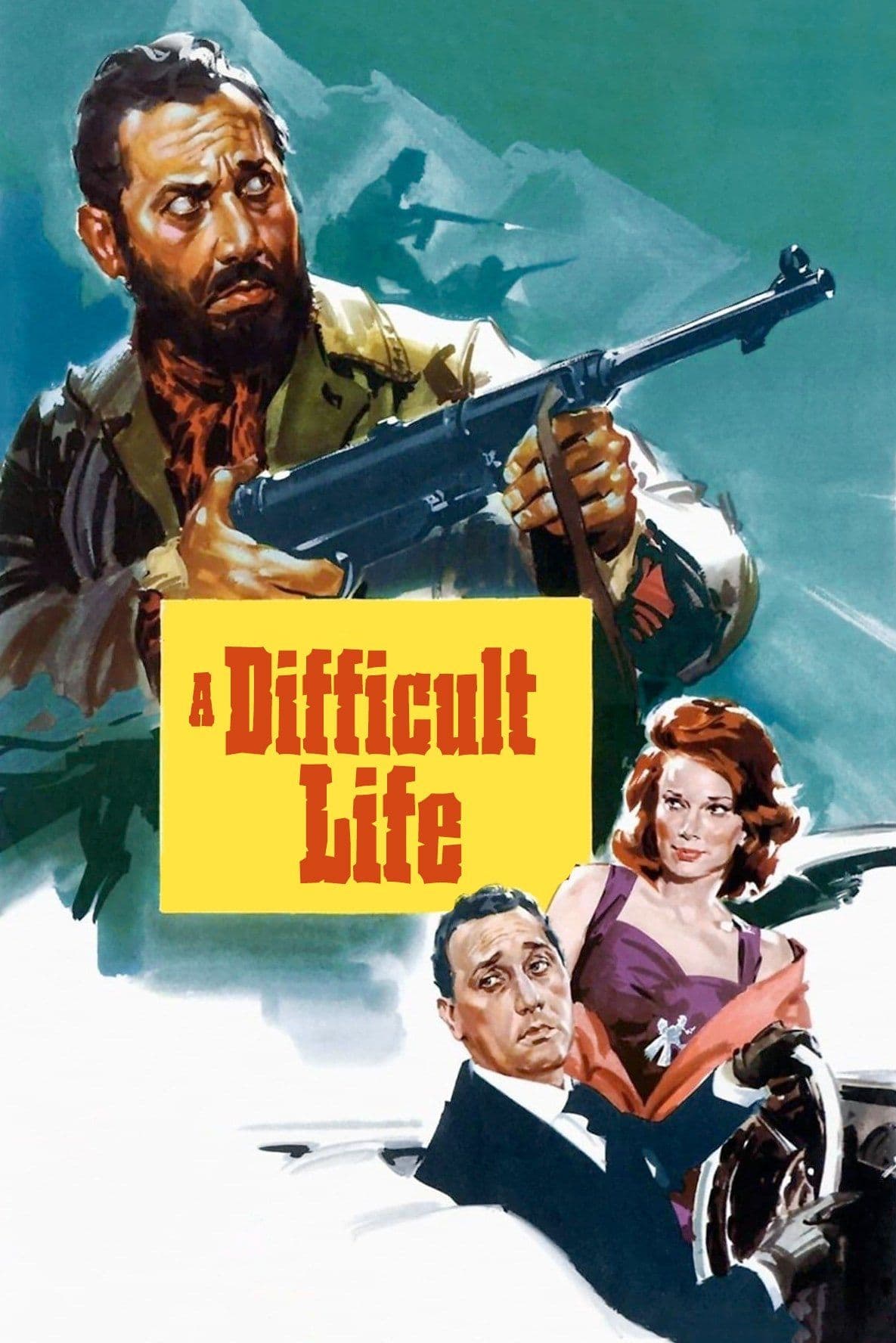

A Difficult Life

1961

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A bitter, cynical, and ruthless look at twenty years of post-war Italy, a period of reconstructive fever and profound moral disillusionment that Dino Risi captures with the precision of an entomologist and the verve of an exceptional storyteller. The film stands as a merciless mirror of a nation that, while rising from physical ruins, finds itself morally impoverished, ready to trade the noblest ideals for the easy seduction of superficial well-being.

How the high-sounding ideals of the Resistance prosaically give way to bourgeois ideals of well-being, money, and frivolous disenchantment. Risi does not merely observe this transition; he analyzes its painful, almost grotesque, consequences. The heroic patriotism of the days of struggle dissolves into the opportunism of the "economic boom," where the memory of past horrors is conveniently buried under the din of new consumption and the pursuit of a fictitious "place in the sun." It is the photograph of a generation that, despite having lived History with a capital "H," finds itself managing it with disarming prosaicism, almost a condemnation. Commedia all'italiana (Italian-style comedy), of which Risi was an undisputed master, finds one of its highest expressions here, balancing bitter laughter with an intrinsic melancholy, revealing the tragic behind the facade of everyday life.

Alberto Sordi looms large in the character Risi carves out for him and is, as usual, the perfect prototype of the defeated. Silvio Magnozzi is not an anti-hero in the romantic sense of the term; he is the embodiment of a certain post-war "Italianness," astute and chameleon-like, capable of adapting to every political and social wind in order to navigate by sight in the agitated sea of modernity. Sordi, with his inimitable ability to merge the pathetic and the grandiose, the vulgar and the tragic, brings to life a man who, despite achieving what capitalist society considers success, remains perpetually dissatisfied, a prisoner of his own choices and renunciations. His famous smirk, often associated with good-natured cunning, here takes on a deep bitterness, revealing the solitude of one who has traded his soul for appearances. His performance is not just an acting performance, but a true anthropological study on the archetype of the average Italian, fragile and overbearing, idealistic and opportunistic.

The narrative follows the events of Silvio Magnozzi, a former partisan saved from Nazi roundups by Elena, an emancipated and strong-willed woman who will become his wife. This premise is fundamental: Elena represents the Resistance not only as a political movement, but as an ethical principle, a moral compass that, unfortunately, Silvio stubbornly ignores. Their relationship is a microcosm of the broader national disillusionment: the love and solidarity of the days of struggle give way to a coexistence built on compromises, where Elena's lucid honesty clashes with Silvio's ambiguous flexibility.

Silvio, after the liberation, becomes a man devoted to climbing the social ladder and securing a place in the sun within the Italian bourgeoisie. His metamorphosis is the beating heart of the film: from idealistic journalist to cynical advertiser, his trajectory reflects the parabola of an entire nation. Every step of his social ascent is marked by a small, almost imperceptible, betrayal of his original principles, until the sum of these small renunciations forms a picture of total moral emptiness. It is not a ruinous fall, but a slow, inexorable erosion.

His ambition will lead him to achieve his goal, but the fruits of his futile labor are nothing more than a different aspect of a defeat already in place before it began. This is the core of Risi's critique: material success is depicted not as a triumph, but as the most insidious of defeats. The "place in the sun" proves to be a mirage, a glittering void where the soul no longer finds a home. The "difficult life" of the title is not so much one of economic hardship, but rather the internal one, made of ethical compromises and loss of identity. A lesson that echoes existentialist disillusionment, where modern man discovers himself a prisoner of his own superficial aspirations.

A memorable scene is the lunch where Silvio and Elena are guests of Princes while the radio announces the victory of the Republic over the Monarchy and the elderly hostess is overcome by illness, while Silvio and his wife celebrate not-so-secretly and, despite all the diners having left the table, calmly finish eating as a bewildered waiter serves them Champagne. This scene is a masterpiece of cynicism and black humor, a perfect allegory of the post-war changing of the guard. The agony of the old aristocracy is contrasted with the ravenous, almost vulgar, celebration of the new bourgeoisie, greedy and tactless. The bewildered waiter embodies the gaze of the people, witnessing a spectacle that is both tragicomic and profoundly significant. It is the triumph of pragmatic hunger for life over rhetoric and decorum, a moment of cruel truth that synthesizes the very essence of Commedia all'italiana at its sharpest peak.

A cynical and bitter Risi, therefore, with a work that attempts to illustrate the difficulties Italian society had to face after a devastating war that had swept away every point of reference. Risi, with his dry direction and sharp writing (Rodolfo Sonego's screenplay is memorable), offers no concessions. His cinema is a scalpel that dissects the wounds of a nation in transformation, laying bare the weaknesses, hypocrisies, and contradictions of an entire people. Unlike other masters of neorealism who sometimes indulged in a glimmer of hope, Risi here is relentless, almost wanting to scream that the real drama was not poverty or destruction, but the loss of the soul.

An irreplaceable document on the commodification of ideologies and the moral decay of men. The film is a lesson in social history, a warning about the ease with which the noblest ideals can be corrupted and transformed into bargaining chips, in a market where value is measured only in terms of profit and opportunism. The entire story of Silvio Magnozzi is a parable about the loss of integrity in a world that rewards adaptability above all virtue.

A theme unfortunately never faded in Italy and always sadly relevant. The "difficult life" of Silvio Magnozzi is not just his own, but that of a nation that, even today, struggles to come to terms with its own ghosts and weaknesses, demonstrating how the dynamics of compromise and transformism, so brilliantly analyzed by Risi sixty years ago, have remained a constant, almost genetic, trait of the Italian character. For this reason, "Una Vita Difficile" is not only a classic of cinema, but a work of inestimable sociological and philosophical value, a bitter pill of truth that retains all its burning relevance intact.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...