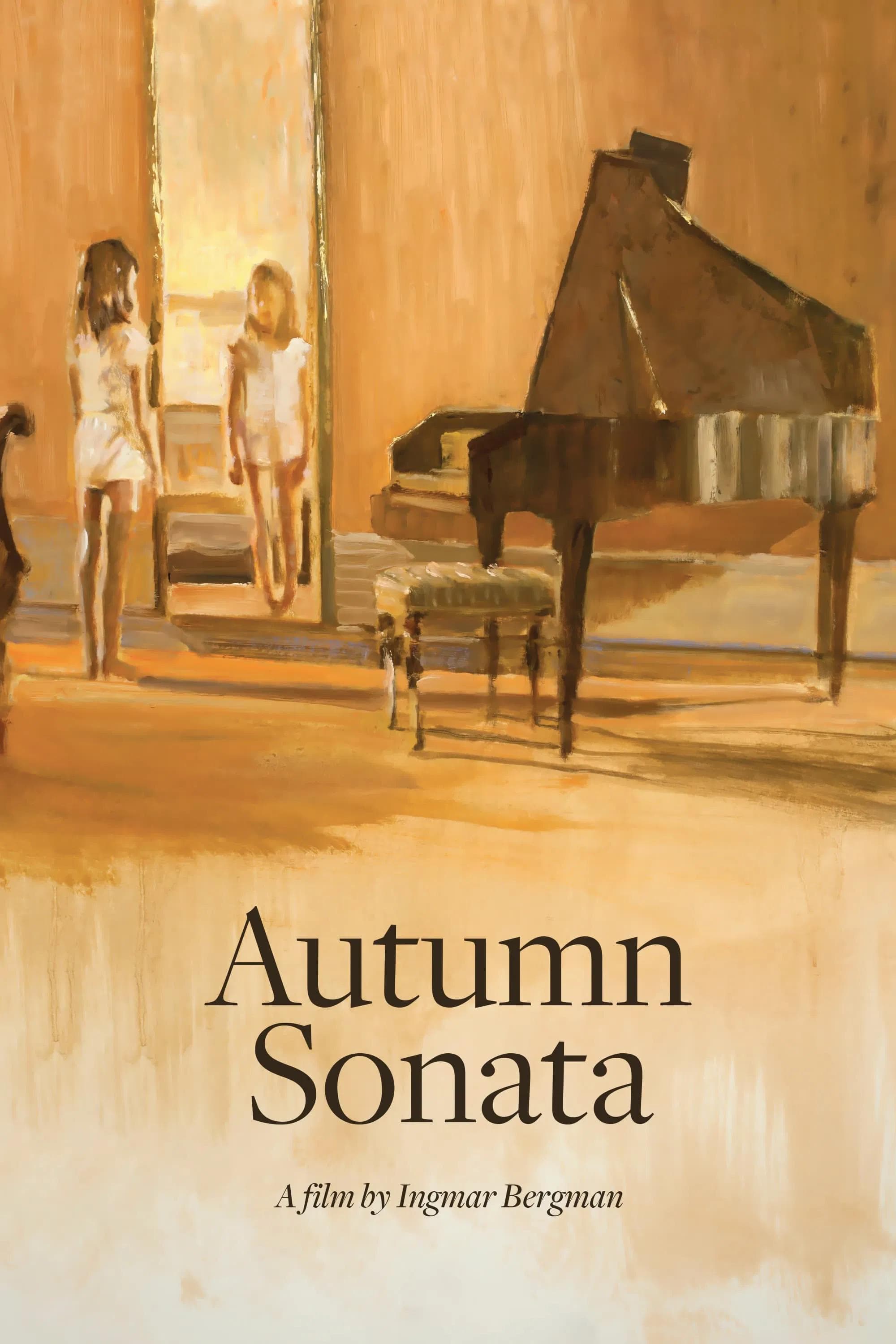

Autumn Sonata

1978

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The only, long-awaited meeting between the two most famous Bergmans in cinema, Ingmar and Ingrid, here in her last, extraordinary role for the big screen, a black swan of painful and majestic beauty. This is not just a note for film buffs; it is the key to understanding the nature of the work. On the one hand, we have Ingmar, the high priest of European existentialism, the soul surgeon who operates in the shadows. On the other, Ingrid, the luminous icon of Hollywood, a face that for decades embodied a form of noble and romantic suffering. Their meeting is the collision of two universes, and the result is a film that is a psychological duel of unheard-of ferocity, a Kammerspiel with the precision of a scalpel and the brutality of an interrogation.

Its strength lies in its emotional universality, which transcends all cultural barriers. The battlefield is a mother-daughter relationship, a territory of love and resentment, of guilt and accusations layered over decades of unspoken words. Ingrid Bergman's performance as Charlotte, a world-famous pianist, is a masterpiece of narcissism and fragility. She is a woman who sacrificed family intimacy on the altar of her art and who now, elderly and alone, seeks absolution that will not be granted her. Opposite her, Liv Ullmann, Ingmar's favorite actress, gives one of her most heartbreaking performances as her daughter Eva. Devoted but filled with long-suppressed anger, her Eva is a volcano of pain that erupts in a cathartic night. It is a film that dissects the idea of family, the inheritance of pain, and the impossibility of true forgiveness. The scene in which Charlotte, with a kindness that is the sharpest form of cruelty, corrects her daughter's interpretation of a Chopin prelude is not a music lesson. It is a microcosm of their entire existence: an act of maternal domination that, masked by professionalism, annihilates her daughter's self-esteem. Anyone who has had a complex relationship with a parent cannot help but feel almost physically involved in this verbal clash, which resembles a chess game played with the soul.

The legacy of this film in exploring the mother-child relationship is immense, and it has created a real standard against which subsequent works have had to measure themselves. Let's consider two seemingly opposite examples. On the one hand, there is the almost mystical cinema of Aleksandr Sokurov with Mother and Son. Sokurov's film is Bergman's spiritual counterpoint: where Bergman stages a verbal war born of a radical misunderstanding, Sokurov films an almost total silence, a symbiotic and devotional bond between a dying mother and the son who cares for her. It is a pictorial, non-verbal work that explores love as total fusion. At the opposite end of the spectrum is Xavier Dolan's explosive Mommy. The Canadian director's film is the punk rock and hyperactive offspring of Autumn Sonata. The intensity is the same, as is the claustrophobia, but the aesthetic is maximalist, pop, screaming. Yet the core of the drama is identical: the all-encompassing and at times destructive nature of filial love, the conflict between the need for protection and the desire for freedom. Bergman, therefore, paved the way, creating a work that functions as a primary text to which subsequent cinema has responded, both in harmony and dissonance.

All this takes place within the rigorous framework of the Kammerspiel, or chamber drama. This genre, which originated in early 20th-century German theater with Max Reinhardt and was later transposed to cinema by directors such as Murnau, was Bergman's favorite form, coming as he did from the theater. The idea is simple but powerful: confine a small number of characters to a closed space for a limited time. Eva's house, the isolated rectory in the Norwegian countryside, is not a backdrop but a psychological decompression chamber. With no distractions and no escape routes, the characters are forced to confront their inner demons and, above all, each other. The aesthetics of Kammerspiel is not an economic choice, it is a philosophical choice. It asserts that the greatest and most universal dramas do not take place on the battlefields of history, but in living rooms, bedrooms, and quiet spaces where human relationships are forged and shattered. It is the elevation of the domestic to the tragic.

And this brings us to the final question: why is Bergman such an important director in the history of cinema? Because, more than anyone else, he understood that the greatest landscape cinema could explore was the human face. His famous close-ups, sculpted by the masterful lighting of cinematographer Sven Nykvist, are not mere shots, they are maps of the soul. Bergman had the courage to tackle the “big questions”—the silence of God, the meaning of death, the nature of identity, the possibility of love—with unparalleled seriousness and intellectual honesty, always rejecting easy answers. He perfected the fusion of the intensity of theatrical language, with its roots in Ibsen and above all Strindberg, and the intimacy of the cinematic gaze. He made cinema an adult medium, a tool for philosophical and psychological inquiry. Autumn Symphony, with its formal perfection, emotional power, and courage in probing the darkest areas of human relationships, is one of the highest peaks of his art and a work whose echo, like that of a masterfully played Chopin prelude, continues to resonate long after the film ends.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...