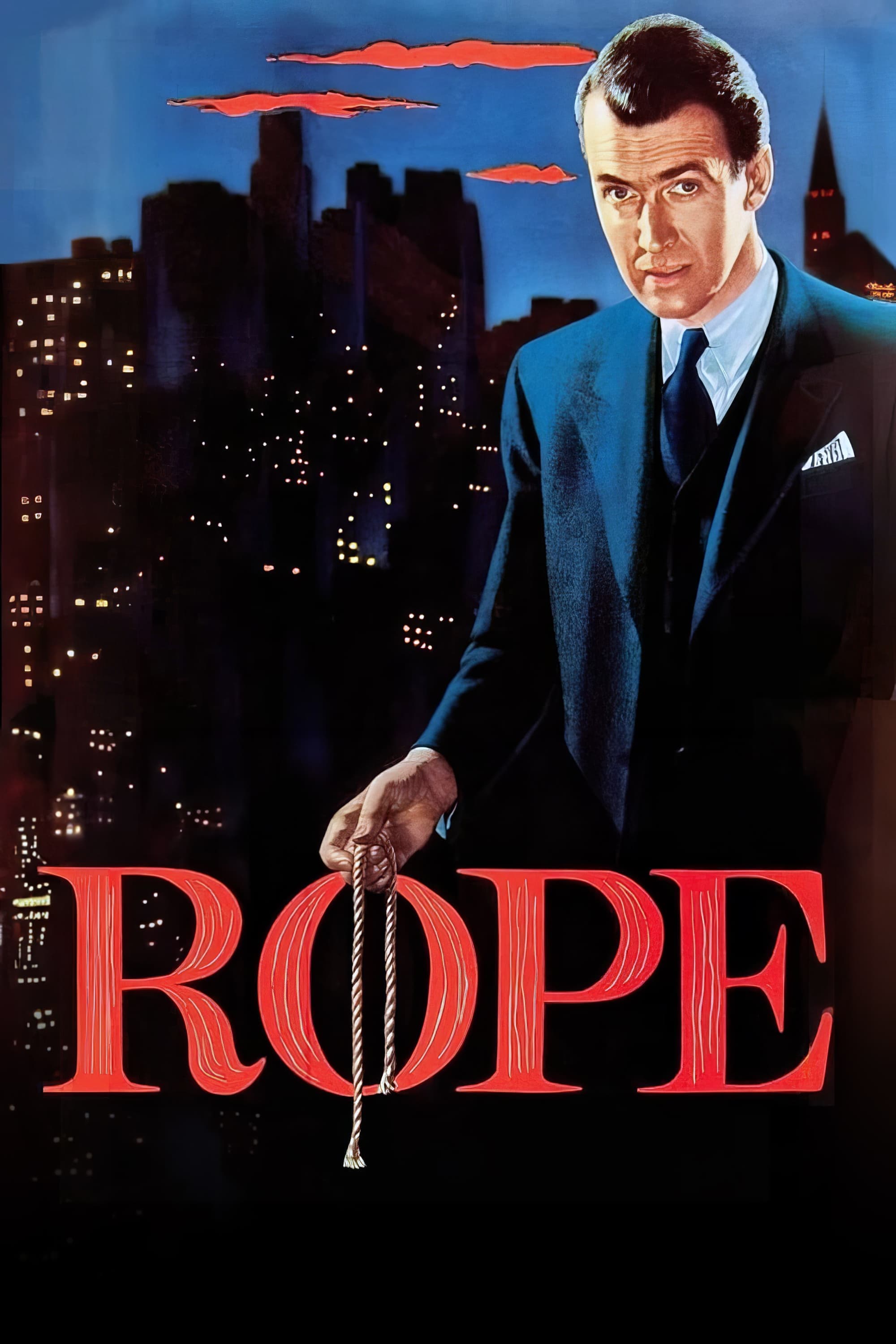

Rope

1949

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

An exercise in style that alters the canons of cinematic language, a genuine leap forward in authorial experimentation that still resonates today with dizzying audacity.

Alfred Hitchcock, the undisputed Master of Suspense, rewrites the rules of the game by conceiving a work filmed in a single continuous take, or rather, with the skillful illusion of one, through the rigorous observance of the three golden Aristotelian unities of time, place, and space. It is not a mere technical virtuosity for its own sake, but a conscious and deeply effective dramaturgical choice. The supposed eighty-minute long take, made possible by ingenious cuts hidden behind an actor's back or the passing of a dark object, is not a mere expedient to impress. It is the pulsating heart of the film, the reason for its inexorable progression, an extreme attempt to recreate before a camera the suffocating atmosphere and perception of a stage. In this way, Hitchcock not only pays homage to the play from which the film is adapted, a 1929 work by Patrick Hamilton that the director went to great lengths to bring to the big screen, but also amplifies its claustrophobia and tension in an intrinsically cinematic way. The spectator's immersion in the real time of the crime and its subsequent dissimulation becomes total, almost visceral.

At the center of this chilling screenplay we find Brandon Shaw and Phillip Morgan, two flatmates (whose homosexuality in the film is only hinted at and remains an underlying thread throughout the narrative, a bold and dangerous subtext for the Hays Code era, yet clearly perceptible in their dynamic of co-dependence and manipulation) who commit a murder for what they call "futile motives." The victim, the innocent David Kentley, is strangled with a kitchen rope and then hidden in an antique chest, which immediately becomes the macabre pivot of the staging. On this very chest, in an act of supreme, glacial arrogance, the two young men set up a banquet for a reception due to take place shortly thereafter. A veritable sacrificial altar to their claimed intellectual superiority.

Among the guests, a gallery of unwitting characters revolving around the unspeakable secret, there is the victim's father and, above all, a literature professor, Rupert Cadell, played by a magnificent James Stewart. Cadell is renowned for his cynical theories on humanity, his hypocritical social rules, and the idea that murder can be justified as an art form or an expression of a superior mind – theories he sowed among his students, and which in Brandon and Phillip found fertile ground to sprout into a monstrous distortion. The tension builds not on "whodunit" – the answer to which is known from the very beginning – but on "will they discover the truth?".

The two murderers react differently to the situation, offering a magnificent study of the psychology of guilt. Brandon, aloof, Luciferian, and endowed with a perverse humor, plays with the crime committed, flaunting an almost Nietzschean intellectual superiority, convinced he is a "superman" beyond common morality. He is excited by the presence of the body hidden in the chest, a trophy to display while the guests chatter around it, unaware of its imminent macabre revelation. Philip, on the other hand, more timid, introverted, and fragile, is on the verge of collapsing, his nerves severely tested during the party by more or less veiled allusions arising from the flow of conversation. He is Brandon's emotional counterpoint, his faltering conscience, the human side that rebels against the horror. Their dynamic is a perverse duet, a deadly dance between control and dissolution.

The finale will be a dialectical vortex, a true clash of intellects and consciences, in which the two murderers inexorably plummet, ultimately seeing their wall of lies miserably crumble before Cadell's devastating and, paradoxically, self-accusatory rationality. It is Cadell himself who realizes that his extreme and provocative theories have been the catalyst for this tragedy, the unwitting "Pygmalion" of evil. The final confrontation, more than an interrogation, is a philosophical debate that reveals the abyss between theory and the monstrous reality of its consequences. This dynamic finds an unsettling echo in the famous Leopold and Loeb case of 1924, two brilliant Chicago students who murdered a boy for pure intellectual pleasure, convinced of their superiority and impunity. A case that undoubtedly influenced Hamilton's play and, consequently, Hitchcock's film, adding a layer of chilling realism to the story.

A film of unparalleled beauty, in which Hitchcock pushes his directorial art to the extreme to reach a dimension that other filmmakers have only desperately glimpsed: the stripping bare of a human conscience through the dialectical power of the word. A work that flows powerfully and unstoppably in a continuous take that gives the impression of being seated in a theater armchair, not only as spectators, but almost as silent accomplices. The sensation of perceiving the power of the Logos in this film is overwhelming and seductive; the word is not only a vehicle of communication, but an instrument of accusation, revelation, and psychological torture. And in this intellectual ballet, nothing matters more to the viewer than that cursed chest and its silently hidden secret, a mute but deafening warning against the dangerous arrogance of the human intellect when it disconnects from empathy and morality. "Rope" remains a masterful lesson in suspense and psychology, a work that, despite its formal singularity, perfectly embodies the obsessions and genius of its author.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...